Uganda

Although English and Swahili are its official languages, many others are spoken in the "pearl of Africa."

Turning back the clock

on a dying language

When Irene Vogel hiked deep into the mountainous forest of southwestern Uganda this past summer, she was in search of something elusive and endangered — not a rare animal or plant species, but a language and, indeed, an entire culture at risk of extinction.

Vogel and a few assistants were seeking surviving Batwa, a people who some two decades ago were forced out of their ancestral homeland where they had lived for thousands of years as hunter-gatherers. Specifically, the UD professor of linguistics and cognitive science was looking for Batwa who remembered their time living in the forest and still spoke or remembered their native language, known as Rutwa.

"Rutwa is an extremely endangered language," Vogel said. "We don't even know how many speakers there still are, but there are probably fewer than 100. When the Batwa had to leave the forest, many did stay in the area, but they learned the local language and stopped speaking their own.

"Some of the people scattered, and even though some others are still living together, their language and culture are rapidly disappearing."

Because Rutwa is not a written language, Vogel noted, when the last elder who can speak it dies, the language will die as well. "If you have no written language and no recordings of your spoken language, then when the language dies, you lose your history, your songs, your herbal medicine.... What do you have left?" she asks.

"You might still identify yourself with the culture, but all you really have left is remnants. You will no longer have access to the knowledge and traditions that had always been passed along by word of mouth."

The goal of her trip to the southwestern tip of Uganda, with UD undergraduate Matthew Herman, was to find as many Rutwa speakers as possible and start to compile a phonetically written list of words and phrases. Herman's participation in the effort was supported by a Community-Based Research Fellowship from UD's Office of Service Learning. Assisted by Vogel's daughter, Rachel, a high school senior, and guides from the nonprofit Batwa Development Program, the group also made video and audio recordings of all Rutwa speakers they were able to interview.

Their trek began just outside the Batwa's homeland in what is now Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, a preserve created by the Ugandan government in the 1990s to protect the mountain gorillas that live there. With the park off limits to everyone except tourists who pay hundreds of dollars in admission fees to see the gorillas, the Batwa now must live elsewhere.

In the town near the park, Buhoma, the researchers located a small group of Batwa who remembered bits of their native language. A grueling, daylong hike brought the team to a tiny settlement where they found two more elders who recalled a small number of Rutwa words. They were able to record some vocabulary from the nine speakers they found, which Vogel describes as only a starting point.

"We recorded lists of some words — names of animals, plants, fruits from the forest — and a couple of songs, but we weren't able to get full sentences," she said. "Some people remember more than others, but it's been 20 years since they lived in the forest, so it's not easy. And it's very painful for some to remember that time, too, since it contrasts sharply with the poverty, illness and ostracism they currently experience."

If Rutwa disappears, Vogel said it would be a loss not only for the Batwa, but also for the world.

"There will be no record of the way the Batwa interacted with nature and among themselves in families and larger groups," she said. "Moreover, we will lose the wealth of factual knowledge about which plants cure various diseases, which insects make different types of honey, how to catch fish and other animals for food, and much more."

Vogel, whose project was supported by a grant from the General University Research program, hopes she can continue the research by focusing on the elders she found with the greatest knowledge of the language. She believes that if she could accompany them into the forests near their homeland, she could spark their memories by pointing out specific plants and places, for example. She hopes, furthermore, that when the elders get together they would inspire each other to remember and speak more Rutwa, and she could make additional recordings.

Even with the invaluable help from the Batwa Development Program, Vogel knows the project faces many challenges, including the Batwa's remote settlements.

But the biggest challenge, she said, is time.

"The elders who remember their time in the forest aren't going to be with us forever, and they're already forgetting so much of the language," Vogel said. "The younger people don't know how to live in the forest — how to hunt, what to eat, what not to eat — and have never even spoken Rutwa. We're really up against the clock."

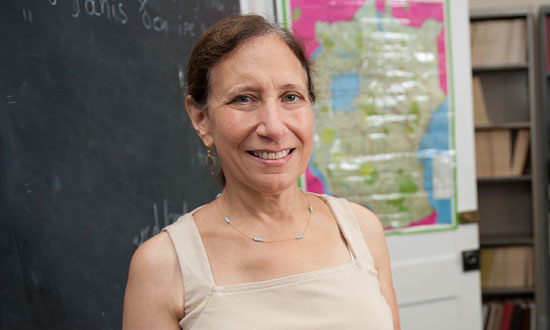

Irene Vogel, professor of linguistics and cognitive science, is working to document Rutwa, the native language of the Batwa people of Uganda before the language is lost.

Irene Vogel, professor of linguistics and cognitive science, is working to document Rutwa, the native language of the Batwa people of Uganda before the language is lost.

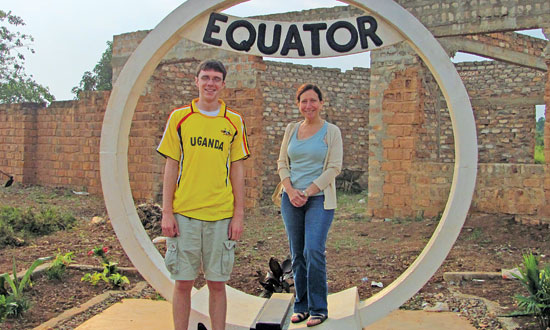

Irene Vogel and undergraduate Matthew Herman (photo far left) at the Ugandan Equator crossing.

Irene Vogel and undergraduate Matthew Herman (photo far left) at the Ugandan Equator crossing.

Irene Vogel and Matthew Herman met with members of the Batwa of Uganda this past summer to compile a list of words and phrases from their endangered language called Rutwa.

Irene Vogel and Matthew Herman met with members of the Batwa of Uganda this past summer to compile a list of words and phrases from their endangered language called Rutwa.

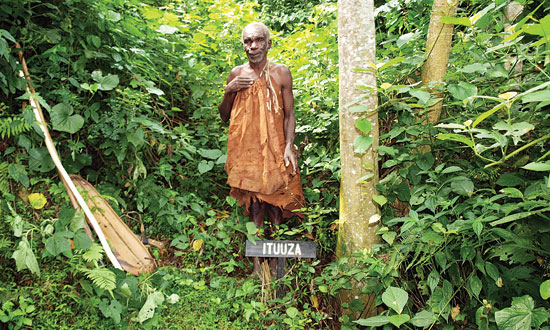

In the forest of southwestern Uganda a Batwa elder tells about medicinal herbs.

In the forest of southwestern Uganda a Batwa elder tells about medicinal herbs.