Stitches in

time go online

National project to create digital archive

of historic American samplers

Sarah Talley of Talleyville, Delaware, must have smiled with satisfaction as she embroidered the last silk threads into her needlework sampler in 1798. At the age of 17, she was relatively old to be completing such needlework, but a close inspection of the stitchery helps unravel the compelling story why.

In addition to the religious poem and fanciful geometric shapes, the leaping hounds, delicate flowers, and proud eagle skillfully embroidered in the uniform x's of cross-stitch to the vertical lines of flame stitch, Sarah documented the names and birth dates of her siblings on her sampler. The youngest two, Lydia and Elihu, were twins born two days apart. Sarah's mother, Lydia Forewood Talley, died the day the second twin was born, on Aug. 16, 1795.

"It's likely that Sarah was too busy caring for the twins to be able to attend school, which is where most girls learned to do needlework," says Linda Eaton, director of collections and senior curator of textiles at Winterthur, the museum of American decorative arts established by Henry Francis du Pont in Winterthur, Del. "Sarah completed her sampler at Mary Sullevan's school the same year her father remarried."

It is such personal stories stitched into historic American samplers that captivate Eaton, a member of a research team working on the Sampler Archive Project. Recently funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the project's goal is to build an online searchable database of American samplers stitched in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

According to Ritchie Garrison, professor of history at the University of

Delaware and director of the Winterthur

Program in American Material Culture Studies, the work is all about enlisting technology to connect the public

with its cultural legacy.

"This project brings together the University of Delaware and the University of Oregon — two great universities with deep strengths in American material culture and advanced digital technology. Joining the project is a consortium of museums, historical societies, and collectors passionate about the study of historic samplers," notes Garrison, who is the principal investigator on the NEH grant. "We hope to do for American samplers what has been done for American quilts, opening another portal into the nation's heritage."

Garrison's co-investigators include Project Director Lynne Anderson, professor of education in the Center

for Advanced Technology in Education at the University of Oregon, and Patricia Keller, who earned both her master's degree in American material culture and doctorate in American civilization at UD.

In the initial phase of the project, Anderson and Keller will work with

curators at three museums: Linda Eaton at Winterthur,

Kirsten Hammerstrom at the Rhode

Island Historical Society in Providence, and Olive Graffam at the Daughters

of the American Revolution (DAR) Museum in Washington, D.C.

The team currently is refining the process for collecting data about samplers and also programming an online database that will make information and digitized images available to the public. At the end of the two-year project, they will have digitized approximately 100 samplers from each of the three pilot sites.

Anderson became interested in samplers when she inherited three from her mother in 2004, one of which had been in the family since it was stitched in 1805 by Mary W. Collins.

"As I began researching sampler history, I was shocked at how little I knew about this aspect of female education. I hadn't known that samplers were made at school, under the direction of a teacher, even though my entire professional life had been in the field of education," Anderson says. "I decided to learn everything I could about samplers and other schoolgirl embroideries, which turned out to be harder than I expected. Much of the scholarship is buried in books that are out-of-print, and the samplers themselves are rarely on view, even when owned by public museums."

In 2008, Anderson and three other sampler scholars launched the Sampler Consortium, an international organization of historians, curators, scholars in material culture, genealogists, educators, collectors and needlework enthusiasts interested in the study of historic samplers. Now with more than a thousand members, the organization conceptualized the Sampler Archive Project and initiated the process that led to the NEH grant.

At Winterthur Museum in Winterthur, Del., from left, Lynne Anderson, Linda Eaton, Ritchie Garrison and Patricia Keller examine several historic samplers. The museum's collection will become part of the searchable online database being created by the Sampler Archive Project.

Proudly displaying numerals and ABCs, scenes of faith and farm life, Bible verses and witticisms, the samplers embroidered by girls in early America not only brightened the home, but also shined the light of literacy into the needleworkers' young lives.

"Sampler" is derived from the Latin word "exemplum," which means "an example to be followed." Young girls, typically from six to 15 years old, would learn different stitches as they created their embroideries, gaining skills they could use for the rest of their lives.

"Sewing skills were vital to a family's welfare," Garrison notes. "Clothing was expensive and usually was mended or remade rather than discarded. In addition, some women depended on such skills to earn a livelihood."

The earliest signed sampler was made in England in 1598 by Jane Bostocke. The work, with its elaborate geometric patterns, a dog, deer and flowers, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

"There were English sampler themes and American sampler themes, and design ideas crossed the ocean," Garrison says, noting that samplers were made in one form or another throughout Europe, the Middle East, Mexico, Central and South America.

Once sampler making became a standard part of the school curriculum for girls, regional and local styles emerged. Teachers often created unique sampler designs, and girls copied the alphabets and motifs associated with their particular school. As they were copying, Garrison says, they might also be learning to read and write, as well as to stitch and embroider.

Eaton notes that some samplers are referred to as "marking samplers," because a girl learned to stitch alphabets and numbers that could be used to "mark" her own clothes as well as family linens with identifying initials.

On the tail of a man's shirt from 1790 in Winterthur's collection, Eaton shows the finely embroidered initials of the owner, with the numeral "12" stitched below.

"If you lived in a city like Philadelphia or Wilmington, you would have sent your laundry out, so you 'marked' it to make sure it didn't get mixed up with someone else's," Eaton says. "The initials identified the owner, and the '12' indicates that this was his twelfth shirt. Because doing laundry was so difficult, you would amass a sizable amount before sending it out," she explains.

Sampler making was embedded in the education of girls of all backgrounds, including free African American students, and Native American girls in mission schools. By the mid-19th century, however, the making of elaborate samplers had fallen out of practice because the curriculum in most girls' schools, especially in urban areas, increased the emphasis on academic subjects. However, stitching samplers remained an important part of the schoolgirl curriculum in some areas of the U.S. and in schools run by conservative religious groups.

Because a sampler often identifies the girl who made it (along with her age and the year it was completed), many have been preserved as family heirlooms. Others are far removed from their original homes, tucked away in museums or private collections. All have stories that are just waiting to be told.

The Sampler Archive Project and its central database will now help connect these historic needleworks to the scholars and interested public who can help tell their stories — collectively, an important part of the American story.

"Our hope is that historical societies, art museums, private collectors and families will help us build this online database by contributing information and digital photographs of the antique samplers in their possession," says Garrison.

According to Anderson, the Sampler Consortium has located more than 10,000 samplers in American collections, although they may not all be American in origin. And there are many more to be found. She and Garrison estimate that there may be as many as 15,000 to 20,000 American samplers in existence.

"Our goal" says Anderson, "is to find them all."

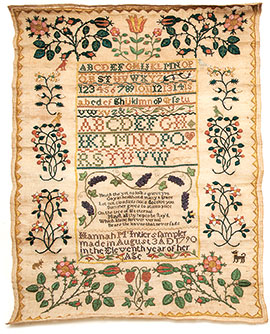

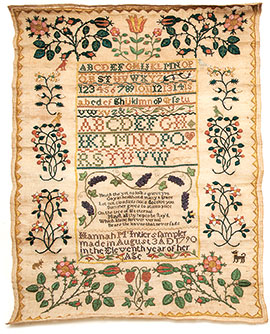

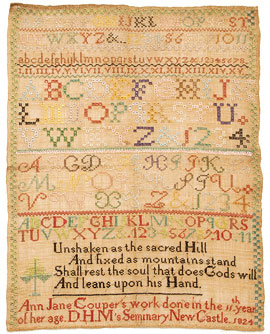

The sampler at left was made by 11-year-old Hannah McIntier in 1790. Bordered by exquisitely stitched blossoms, it features this verse framed in a grapevine motif:

"Youth tho' yet no losses grieve you, Gay in health and many a grace, Let not cloudless skies deceive you, Summer gives to autumn place, On the tree of life eternal, Mayst all thy hopes be lay'd, Which alone forever vernal, Bears the leaves that never fade."

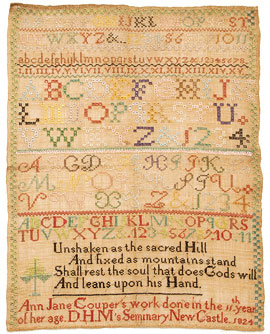

At right is 11-year-old Ann Jane Couper's finely stitched sampler with its clearly visible verse. It was made at D.H.M.'s Seminary in New Castle, Del., in 1824.