Egypt

Founded by Egypt's King Ptolemy II in 275 B.C., the port of Berenike was once a thriving cultural hub.

Uncovering the

secrets of Berenike

Archaeologist Steven Sidebotham discovers the cosmopolitan trappings of a truly global economy at the ancient port of Berenike in Egypt's Eastern Desert.

It's commonly accepted that today's economy is a global one, but make no mistake about it, says Steven Sidebotham: We aren't the first people to experience such a phenomenon, and it isn't unique to the last century — or even the last millennium.

"You hear a lot about globalization today, but there was a 'global economy' linking Europe, Africa and Asia during the first century of the Christian era, and the city of Berenike is a perfect example of that," says the University of Delaware history professor and archaeologist, who has been uncovering the secrets of the ancient Egyptian port for almost two decades. "In the Roman era, Berenike became a very international emporium, trading as far west as Spain and as far east as Indonesia, and it was an extremely cosmopolitan place."

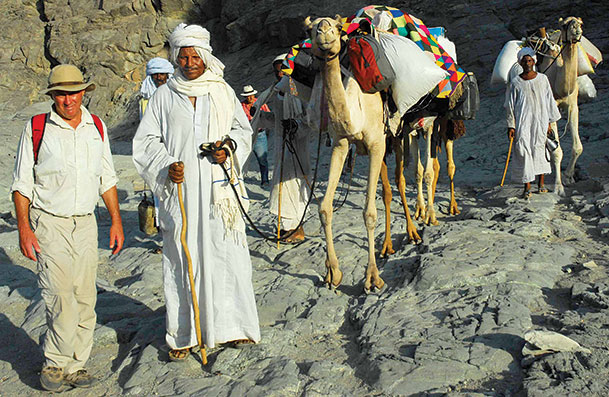

Working painstakingly and in severe desert conditions where every drop of water and all food, supplies and equipment must be hauled to the site from great distances, Sidebotham travels to the Red Sea port every year. There, layer by layer, the ancient, multicultural city that for centuries was a trading hub of the Roman Empire reveals a new chapter of its story to him and his international team.

"This is an amazing, huge site with excellent preservation because of the hyper-arid climate," Sidebotham says. "We've probably uncovered only about 2 percent of the ancient city, so there are still several lifetimes' worth of work to be done."

The project began in 1994 and has survived government upheavals, administrative delays, changing international partnerships, budget shortfalls and even this year's political turmoil that ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. From 1994 until 2001, the archaeological dig was a joint project with Leiden University in the Netherlands and then with the University of California at Los Angeles; since 2008, it has operated in collaboration with the University of Warsaw and Iwona Zych, who is co-director.

Operating on a shoestring budget that often includes large infusions of his own money, Sidebotham and his colleagues have documented a thriving culture that existed in the city for some 800 years, beginning about the middle of the third century B.C.

"This project is not just my research; it's my life," Sidebotham says. He publishes annual field reports detailing his findings and has authored or co-authored several books, the most recent of which is Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route, published in January by the University of California Press. In 2008, the Discovery Channel featured his work in the documentary "When Rome Ruled Egypt."

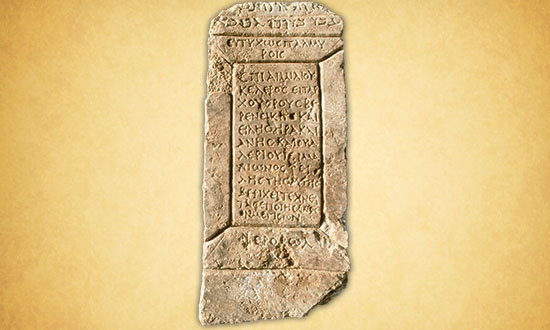

On the edge of Egypt's Eastern Desert, Berenike thrived as a trading port for goods from Europe, the Middle East, south Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and southern Arabia. Sidebotham's excavations have turned up such varied items as Indian-made pottery, textiles, ships' sails and beads, stone and wooden figurines of Venus, ships' timbers made of cedar from Lebanon and teak from southern India, a clay jar containing decorative silver pieces, Roman glass, a gold and pearl earring, sapphires and other gems, a mother-of-pearl cross and slivers of Turkish marble used as veneer for walls or floors. Several inscriptions carved in Greek on large stone blocks have also shed light on the religious lives of the city's residents.

UD AUTHOR

Amazon.com calls Sidebotham's latest book "an intriguing read, an accessible account full of fascinating finds and careful analysis."

A particularly significant find was made in 1999, when the team discovered a large jar embedded in the courtyard floor of the Serapis Temple, which contained nearly 17 pounds of black peppercorns from the first century. Cultivated at the time only in southwestern India, peppercorns were highly prized in ancient medicines and religious rituals as well as cooking. The large quantities found throughout the city confirmed that Berenike was not only a transit point for this and other exotic merchandise but also a consumer of these commodities.

The city was founded in the third century B.C. for the importation of elephants, gold and ivory from regions of Africa south of Egypt. The intimidating size of elephants, Sidebotham says, made the animals the tanks of ancient armies.

In the Roman era, Berenike became a bustling boomtown, where merchants came to trade a wide assortment of goods and where many grew very wealthy. Despite the harsh living conditions that included extreme heat, lack of rainfall and plenty of insects, the city became home to families as well as businessmen. Sidebotham's team has discovered human remains and numerous artifacts indicating that people of all ages as well as backgrounds lived in the city.

Goods came to Berenike after a two-week trek across Egypt's Eastern Desert from the Nile to the Red Sea, where they were loaded onto ships and traveled down the Red Sea and over the Indian Ocean —assisted by the annual monsoon winds — to India, southern Arabia and coastal Africa. When the winds reversed their course months later, the ships traveled back to Egypt laden with products for Mediterranean markets.

Based on ancient writings from the first century B.C. and first century A.D., Sidebotham says, at least 120 ships carrying a minimum of 75 tons of goods each may have sailed each year between India and Berenike and her sister ports farther north along Egypt's Red Sea coast. Because the vessels carried such valuable cargo as spices, incense and plant and animal products, he estimates that the trade amounted to more than $10.5 trillion in imports over some five centuries of activity in Roman times.

"Berenike was a very cosmopolitan place where people — men, women and children, many of whose names and ethnic and social statuses we have discovered — lived, worked and perished," Sidebotham writes in his latest report summarizing work at the site last January and February. "It was a cultural melting pot where the common interest was making a great deal of money from the lucrative trade ... that passed both ways through the emporium."

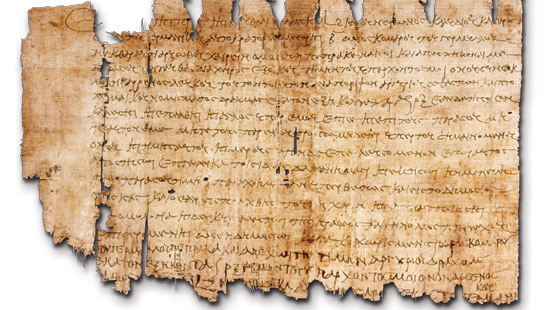

Writings on scraps of papyrus have yielded everything from a personal letter, in which a mother complains that her son doesn't write her as often as she would like, to a surprisingly detailed bill of sale for a donkey. Like Americans today, Sidebotham says, the merchants of ancient Berenike were litigious businessmen who carefully spelled out every aspect of a transaction.

Each year, the site reveals more information about its past, Sidebotham says. This year, for example, the team found a pet cemetery containing the remains of 17 dogs and cats, ship timbers and other maritime artifacts from the harbor area, and a trove of objects from an early Roman-era trash dump.

In addition, the project has yielded much information about life in and around the city, Sidebotham says. Findings include artifacts from religions with a variety of deities and evidence of 12 different written European, African and Asian languages, including one that is as yet unidentified.

Tight budgets mean that less time and manpower is now available, Sidebotham says, but he notes that the past three years have had "really spectacular" results and that he has every intention of continuing.

"This site is massive," he says. "There's no way, by excavating it properly as we have been doing, that it could be completed in my lifetime. There's probably enough work for four or five more generations of archaeologists."

Archaeologist Steven Sidebotham, Professor of History at the University of Delaware

Archaeologist Steven Sidebotham, Professor of History at the University of Delaware

Dated July 26, 60 A.D., this papyrus from Berenike is a surprisingly detailed bill of sale for a white male donkey and its saddle for 160 drachmas.

Dated July 26, 60 A.D., this papyrus from Berenike is a surprisingly detailed bill of sale for a white male donkey and its saddle for 160 drachmas.

Crocodile sphinx found at the Serapis Temple in Berenike.

Crocodile sphinx found at the Serapis Temple in Berenike.

Graffito of a sailing ship dating to the 1st century.

Graffito of a sailing ship dating to the 1st century.

The well-preserved "Administration Building," carved from slabs of schist, is in the ancient emerald mining town of Sikait, just north of Berenike.

The well-preserved "Administration Building," carved from slabs of schist, is in the ancient emerald mining town of Sikait, just north of Berenike.

Bilingual inscription in Greek and Palmyrene dedicating a statue to a religious deity. It records several Roman soldiers plus the Roman governor of Berenike by name.

Bilingual inscription in Greek and Palmyrene dedicating a statue to a religious deity. It records several Roman soldiers plus the Roman governor of Berenike by name.

In 275 B.C., Egypt's

In 275 B.C., Egypt's