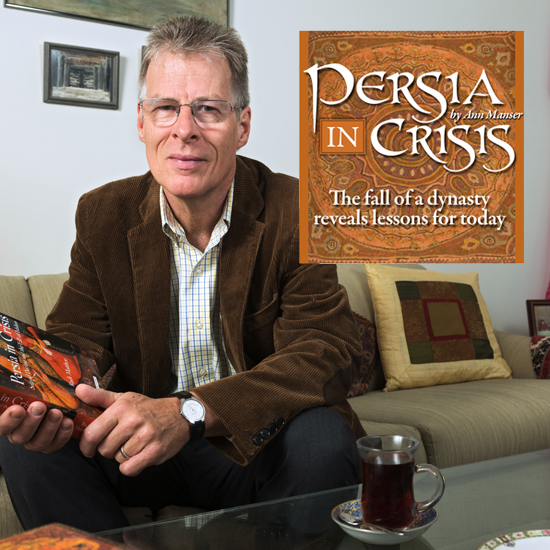

By Ann Manser Office of Communications and Marketing

Sunni Muslims who feel oppressed by their Shi’i central government. A shah presiding over what many see as a successful and prosperous Iran but who is overthrown in a surprise attack. A band of fierce Afghan fighters from Kandahar.

These are all elements in a story that may sound familiar to modern Americans but is actually centuries old—the fall of the reign of the Safavids in 1722, a dynasty that had ruled Persia (now Iran) for 221 years. It’s a story that’s told from a new perspective by Rudi Matthee, John A. and Dorothy L. Munroe Chair in History at the University of Delaware, in his award-winning new book, Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan, published by I.B. Tauris.

Ethnic Turks were highly successful as “the empire builders of the time,” Matthee says, but all the states they established went through phases of rising, flourishing and eventually declining. The Safavid empire in Persia may have seemed to be breaking that cycle, still seemingly going strong in 1722, more than two centuries after its creation. The capital city Isfahan was known for beautiful mosques and monuments and centers of learning, and the shah ruled from his palace there.

But then, in 1722, about 10,000 Afghans from Kandahar, on the outer edge of the empire, invaded.

“How was this ragtag band of Afghan tribesmen able to come in and take down the empire?” Matthee asks. “The seemingly sudden collapse of Isfahan ushered in an entire century of chaos in which warlords ran amok.”

Historians have traditionally attributed the Safavid collapse, he says, to weakness caused by “lust and play” among the rulers. That explanation follows the idea that the first generations of rulers in any dynasty build, and then later generations enjoy the results, finally ignoring the work that needs to be done and focusing instead on their own pleasure.

Although the last Safavid rulers were indeed weakened by their lifestyle, Matthee says, the empire had become vulnerable for other reasons as well. Serious problems affected Persia’s finances and military, and the far-flung empire was becoming increasingly factionalized and difficult to control from a central point.

“We’ve had a view that the shah controlled the entire country, but that’s simply impossible,” Matthee says. “Iran is a vast country, with stretches of deserts and mountains, and at the time, no good means of communications.”

The remote areas of the empire became more and more isolated from the rulers in Isfahan, he says. When the Safavids ran short of money, they stopped supporting the outlying areas and started taxing them heavily. That led to increased resentment by tribal groups such as the Afghans, who as Sunni Muslims already felt oppressed by the Safavids and their state-sponsored Shi’i religion.

By the time the Afghans attacked, Matthee says, the empire “had already become hollowed out from within,” and financial problems had weakened the military.

Although the attackers were able to overthrow the Safavids, they were a tribal and semi-nomadic group unable to govern, and their rule lasted only a short time before it too collapsed. “After a couple of years, they were swept up in the turmoil they themselves had unleashed … plunging Iran into a century of darkness and poverty and exhaustion,” he says.

Matthee sees some lessons for today, including the way a state religion that excluded citizens of other faiths ended up alienating them in a manner that was “playing with fire.” And, he says, isolation from the areas on the periphery has always caused problems for centralized rulers, from ancient times to the 20th century’s Soviet Union.

Persia in Crisis has won attention and acclaim. Reviewers have called the book “groundbreaking” and praised its research based on materials in numerous languages.

“The author displays an admirable knowledge of the sources in Persian, a rich vein of contemporary archival material and the studies written in all major European languages, clearly a feat which will not be easy to follow,” writes J.P. Luft of the Centre for Iranian Cultural Studies at the University of Durham.

Matthee has given lectures on his book in Sapporo and Tokyo, Berlin, Ottawa and Toronto, at Yale University and, with a book signing, at the Library of Congress. In July, the work was one of two selected for the annual Book Prize Award from the British-Kuwait Friendship Society for best scholarly books on Middle Eastern studies.

Matthee, who joined the UD faculty in 1993, teaches Middle Eastern history, with a research focus on early modern Iran and the Persian Gulf. His previous books include The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500–1900, which won both the Albert Hourani Book Prize from the Middle East Studies Association of North America and the Said Sirjani Award for the best book on Iran from the International Society for Iranian Studies.