By Diane Kukich College of Health Sciences

On Mother’s Day of 2008, high tides, strong northeast winds and heavy rains left a handful of tiny communities along the Delaware Bay in Kent County under several feet of water.

The storm left in its wake one fatality, dozens of people homeless and more than $1 million in property damage, but it also prompted state officials and University of Delaware researchers to put their heads together to develop an early warning system for coastal flooding to facilitate planning in the future.

The result was an alert notification system and website displaying pertinent information regarding forecasted local water levels. It initially focused on six coastal communities along the Delaware Bay—Leipsic, Little Creek, Pickering Beach, Kitts Hummock, Bowers Beach and Slaughter Beach—for testing the system, but it has since been expanded.

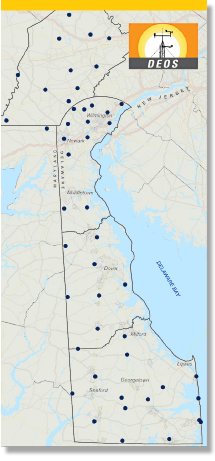

Launched in 2011, the Coastal Flood Monitoring System (CFMS) supports planning and emergency management for Delaware Bay communities before and during coastal storm or high tide events. It was developed by John Callahan, a research associate for the Delaware Geological Survey (DGS), and Kevin Brinson, a researcher for the Delaware Environmental Observing System (DEOS). The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control and the Delaware EPSCoR program funded the project.

The CFMS includes several elements:

All the information is tailored to specific locations, so an official from Bowers Beach, for example, can look at inundation maps and use them to make decisions about evacuating residents or calling in rescue crews.

“Delaware has coastal flooding issues just about every time there’s a major storm, and, with increases in sea level, we have the potential for these incidents to occur more frequently,” says Dan Leathers, professor of geography in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment and Delaware state climatologist. “The monitoring system won’t alleviate flooding, but it can help us better prepare for the effects of coastal flooding on people and property.”

Callahan points out that in coastal Kent County, the roads are barely above water under normal conditions.

“Let’s say it’s high tide and we get just a small amount of onshore wind—that’s all it takes to cause flooding in this area,” he says. “That’s why displaying the road profiles on the website is an important feature for planners and rescue personnel as they try to answer questions like ‘Can we get a fire truck through or do we need to use boats to get people out?’ ”

The team currently is working on the next generation of the system that will go as far north as New Castle and as far south as Lewes. It will feature increased quality and resolution of forecasts, an improved alerts system and a new web interface.

Leathers explains that expansion of the system to other areas of the state involves much more than just extending its geographic boundaries. “We have to consider different hydrodynamic issues in each of these areas,” he says.

While the monitoring system provides a service to coastal communities, it is also firmly grounded in research. The team is comparing model predictions with actual behavior to improve system accuracy.

They also have started taking measurements in preparation for creating a similar system for Delaware’s Inland Bays, which are influenced by different climatic and hydrodynamic phenomena.

Leathers applauds the state for the support they give to DEOS and DGS researchers.

“There’s a lot of environmental observation going on in the state, which really helps with projects like this,” he says. “There are more monitoring stations here than there are in many states much larger than Delaware.”

When a weather emergency threatens Delaware, the Office of the Delaware State Climatologist and the Delaware Geological Survey (DGS), both based at UD, are integral members of the team that rallies to deal with the potential crisis.

Whether it’s a hurricane, nor’easter or major snowstorm, weather emergencies in the First State usually prompt concerns about flooding, and that’s where these offices come into the picture.

In the case of an impending hurricane like Sandy in October 2012, the UD group gets involved in briefings and conference calls three or four days before the storm is expected to hit.

They use a variety of tools, including the Coastal Flood Monitoring System, as the basis for advising the Delaware Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) about the potential for coastal flooding or inland flooding from streams.

If it appears that a storm is going to have a major impact on Delaware, DEMA’s Technical Assistance Center is activated, and the state’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) is opened. At least two members of the UD team join the 50 to 100 other people staffing the EOC, including representatives from state agencies, utility companies and the Red Cross.

“I think we provide a pretty important resource for the state by helping answer questions about storm behavior, water levels in streams and coastal areas, and when those levels will peak,” says Delaware State Climatologist Dan Leathers. “We can’t change the weather, but we can help ensure that people are safe during extreme events.”