VOL. 4 / NO. 1 INTERACTIVE PDF ![]()

By teresa messmore College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment

Along much of the East Coast, long stretches of thin, sandy islands provide a buffer from surging waters during storms and help protect the mainland. UD researchers are studying how these barrier islands are changing to better predict coastal response to sea level rise.

“Barrier islands are the canaries in the coal mines, so to speak, in terms of sea level impacts,” says Arthur Trembanis, associate professor of geological sciences and oceanography. “They are dynamic and finely tuned systems that can be readily—and often dramatically—perturbed by impacts from storms and sea level rise.”

Barrier islands form when waves and wind push sand into mounds that gradually enlarge into dunes and then islands, with tides and currents bringing in water at certain spots to create inlets. Changes to any part of this delicately balanced system can re-form an island’s shape and location, as well as the surrounding bays and lagoons. In fact, East Coast barrier islands were once much farther out to sea near the edge of the continental shelf and have moved landward as water levels crept higher.

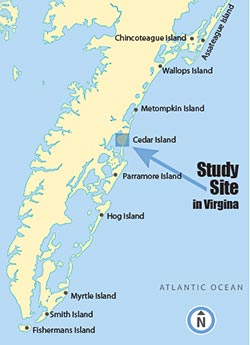

Delmarva’s barrier island system begins at Cape Henlopen and extends all the way down through Assateague Island to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Trembanis and graduate student Stephanie Nebel are examining uninhabited Cedar Island in Virginia, about 90 miles south of Fenwick Island, Del., as a natural laboratory.

They’ve found that the shoreline there has been retreating toward the mainland at increasingly rapid rates. Shoreline retreat was three times faster from 1994–2007 than 1852–2007, changing from 4.1 to 12.6 meters (13.4 to 41.3 feet) per year.

Trembanis said the trend may point to Delmarva barrier islands showing early signs of a shift to “runaway transgression,” where the islands become smaller and thinner while the inlets and back-bay areas become bigger.

Rising sea levels contribute to this island shrinking, but storms are also a factor. Barrier islands are frequently exposed to hurricanes and tropical storms, when widespread washover can alter the shoreline position drastically. In September 2006, for example, Tropical Storm Ernesto diminished shorelines on Cedar Island by as much as 55 meters (180 feet).

“There is an important feedback loop between sea level rise, storminess and the response of the barrier islands,” Trembanis says.

The frequency of intense storms has increased since 1980, which the scientists found to be directly related to the rate of erosion at Cedar Island. With the Virginia barrier islands eroding faster than the rest of the Mid-Atlantic as a comparative hotspot, next they are investigating the role of offshore sand deposits—or lack thereof—in erosion rates.

“We’re curious to see if patterns of hotspots are being influenced by the conditions offshore,” Trembanis says.