Meeting Jeanne:

A medieval life illuminated

Gabrielle Parkin, doctoral candidate in late medieval literature, with the Book of Hours at the University of Delaware Library’s Special Collections.

Gabrielle Parkin, doctoral candidate in late medieval literature, with the Book of Hours at the University of Delaware Library’s Special Collections.

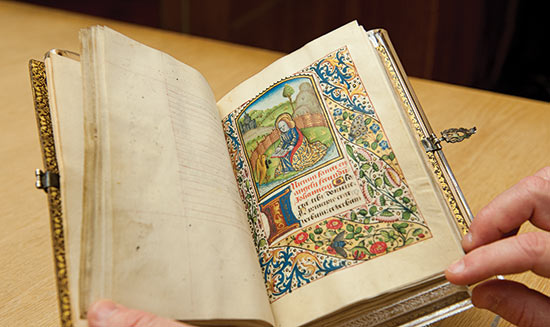

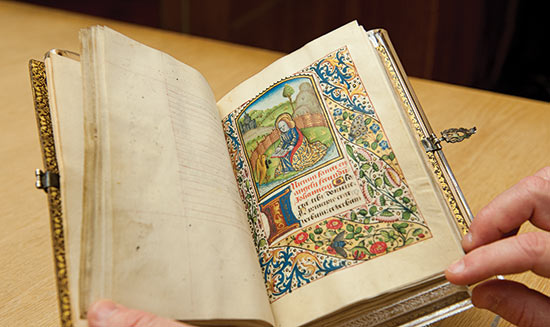

Folio from the University of Delaware Library’s Book of Hours. The book was produced in northern France in the late fifteenth century.

Folio from the University of Delaware Library’s Book of Hours. The book was produced in northern France in the late fifteenth century.

In the opening folio of the Book of Hours at the University of Delaware Library is an inscription in French to Jeanne Cinot from her father, who instructs that if lost, the book should be returned, “for without these hours she cannot say her prayers.”

Like the gold letters adorning its beautifully illustrated pages, this book would have illuminated the spiritual life of Jeanne, a young woman in France in the early sixteenth-century, according to Gabrielle Parkin.

Parkin, a native of Tinton Falls, N.J., is a doctoral candidate in late medieval English literature at UD. She has been examining how the Book of Hours housed in UD’s Special Collections was made, its contents and its role in the daily life of Jeanne and women like her. Jeanne’s name is but the first of three inscribed in the edition.

The Book of Hours was the “bestseller” of medieval times, popular throughout Europe from the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries. If a family owned just one book, it would be this one, Parkin says.

“Jeanne’s represents a manuscript produced for the middle class, merchants and artisans who were financially successful, but not of the landed elite,” Parkin says, pointing out the rough parchment and smudges. Finer editions might include the owner’s portrait and more decoration in even more magnificent colors.

“It was made to be used, and there is some evidence that it’s been thumbed through,” Parkin says of the book. “That’s why I like it so much.”

Parkin pages carefully to a painted scene of Mary holding the Christ child. The faces of mother and child are nearly faded away. Was it from fervent prayer, as Jeanne touched or kissed their faces? Was it due to tears of joy — or sadness — by multiple owners over the years?

Prior to the purchase of this illuminated manuscript in 2008, which was made possible by a special 50th anniversary gift of $100,000 from the University of Delaware Library Associates, UD students and faculty had to make do with facsimiles of Books of Hours for their research and teaching.

The edition acquired by UD was produced in northern France, likely in the city of Amiens, during the late-fifteenth century. Written in Latin and French on vellum, the manuscript consists of 130 leaves and has 10 large painted scenes or “miniatures” and 17 decorated initials. The prick marks visible along the edges are evidence of the metal styluses that kept the pages aligned as the book was born.

Teams of calligraphers and artists would have created the original artwork, illuminations and fancy lettering, with the size of the ornate initial letter indicating the importance of the prayer that followed it, Parkin notes. A small amount of gold is expertly applied to specific letters.

The painted scenes, ranging from shepherds with their flocks learning of Christ’s birth, to the scene of Christ’s resurrection, are surrounded by elaborate swirls, hearts and trefoils, vines and flowers, strawberries (a symbol of virginity), bees, butterflies, bunnies, birds including a peacock, even a monkey. A court jester and dragons also appear, to the reader’s surprise and delight.

The humans depicted offer the reader a lens into medieval fashion — shepherds in stockings wear tunics with cloaks draped around their necks, while Mary is portrayed in full, flowing dresses with modest necklines and, in one view, a small collar.

This painted scene of the Annunciation of Christ helped instruct readers in the correct posture for prayer. The surrounding illustrations also speak to the sense of humor of medieval artists. Note the court jester near the bottom of the folio.

Leading a spiritual life

A typical Book of Hours was organized into sections or “hours,” each containing prayers, psalms, hymns and other devotional texts to be recited or sung at designated times of the day, corresponding with monastic hours of prayers. Typically, prayers were said eight times a day, beginning at midnight, then at dawn, at two intervals in the morning, at noon, at mid-afternoon, at sunset, and ending at bedtime in the evening.

The contents generally included a set of prayers called the Hours of the Virgin, lessons from the gospels, penitential psalms, portions of the Office of the Dead, and a calendar with lists of feast days. The term “red letter day”actually had its origins in these illuminated manuscripts, as feasts of special importance came to be written in red ink to highlight them, Parkin says.

Although Books of Hours were not exclusively women’s books, they often were given to women as wedding gifts, and they would become important household objects.

“A Book of Hours is not a self-help book — not like Dr. Spock — but it was a means to teach your kids how to read, how to pray to Mary and to different saints, and how to live a pious life,” Parkin notes.

The Book of Hours would instruct the mother in how to perform devotions, and she, in turn, would teach her children. The prayers (only the beginnings of prayers were typically included) would help her to form a more personal relationship with God, and particularly with the Virgin Mary, whom she would ask for intercession in prayer, according to Parkin.

In the scene of the Annunciation in Jeanne’s book, the Virgin Mary is shown receiving the revelation of her divine pregnancy from an angel while kneeling before a book on a desk, possibly her own Book of Hours. Besides demonstrating the prayerful posture to be adopted, kneeling with hands together, the illustration shows the Virgin Mary’s book cloaked in green fabric, perhaps to protect the manuscript, another visual message of instruction.

“Many people don’t realize that books were very much a part of the lives of women at this time, and some women engaged in private, contemplative reading. A desk in one’s room, like the desk shown before the Virgin Mary, could make reading even more comfortable,” Parkin notes.

“I just love this stuff,” Parkin half-whispers excitedly, as she pores over another page.

In an October 2011 article in the Newsletter of the University of Delaware Library Associates, Parkin thanks the Library Associates for the opportunity to work with an original Book of Hours, which has inspired her to focus her research and scholarship on manuscript history.

“But perhaps most importantly, it has allowed me to get to know Jeanne Cinot a little better,” Parkin writes. “Through a study of the book itself, as well as the prayers and production of Books of Hours, I have been able to glean a sense of the expectations and assumptions that a newly married woman of the sixteenth century would have and how she might have tended for the spiritual well-being of herself and her family.”

Today, Parkin says she can easily imagine Jeanne reading her Book of Hours.

“Seeing the light reflecting off the manuscript would have been a really stunning sight,” Parkin notes.

Gabrielle Parkin, doctoral candidate in late medieval literature, with the Book of Hours at the University of Delaware Library’s Special Collections.

Gabrielle Parkin, doctoral candidate in late medieval literature, with the Book of Hours at the University of Delaware Library’s Special Collections.

Folio from the University of Delaware Library’s Book of Hours. The book was produced in northern France in the late fifteenth century.

Folio from the University of Delaware Library’s Book of Hours. The book was produced in northern France in the late fifteenth century.