KENYA: Named after Mt. Kenya, Africa's second highest peak, it covers an area twice the size of Nevada. The country's population of 44 million comprises more than 40 indigenous communities, each with its own mother tongue. The majority of the people speak three languages. English and Swahili are the official languages.

KENYA: Named after Mt. Kenya, Africa's second highest peak, it covers an area twice the size of Nevada. The country's population of 44 million comprises more than 40 indigenous communities, each with its own mother tongue. The majority of the people speak three languages. English and Swahili are the official languages.

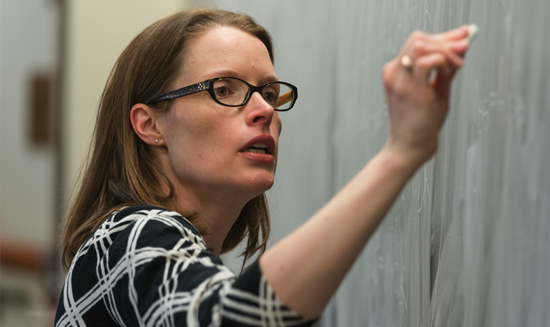

Adrienne Lucas brings her experiences from Africa into her classroom at UD to encourage students to think critically about development policies.

Imagine if a country could harness the power of education to positively impact its economic development. That's the idea behind universal primary education, one of the United Nations' 2015 Millennium Development Goals, and resultant programs like the Kenyan Free Primary Education (FPE) initiative.

Before the FPE policy was enacted in 2003, many children in Kenya could not attend school due to the cost. Additionally, an estimated 1.1 million Kenyan children have lost one or both parents to AIDS.

Yet while FPE and similar programs are becoming increasingly common in developing countries, little research has examined the impact of these programs on student achievement or educational attainment and whether investment efforts have been successful.

Enter Adrienne Lucas, assistant professor of economics in the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics at the University of Delaware.

A development economist, Lucas specializes in the economics of education and disease. Currently, her research focuses on the effects of Kenya's FPE program, as well as secondary school quality, on student achievement in that country. She also is examining the achievement return to a primary school literacy intervention in both Kenya and Uganda, and the intergenerational effects of adult antiretroviral therapy in Zambia.

"Free Primary Education was heralded as the solution to bring universal primary education to all students, but almost immediately after its implementation worries emerged about its true ability to bring students into school and the effect on student achievement," says Lucas. "So the question is, are students learning more, and are more students completing school?"

To that end, Lucas examined test score and primary school completion data from the six years around the implementation of the program and made site visits to Kenyan primary schools to talk with principals to gather information. Based on these data, she has been able to estimate the effect of FPE on primary school completion and student achievement.

Her findings, which were published last year in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, suggest that FPE increased the number of students who completed primary school, including students from disadvantaged backgrounds, and led to, at most, only a small score decline for students who would have been in school anyway.

Lucas makes the effort to bring her experiences in Africa, as well as journal articles and popular press excerpts, into her classroom at UD to encourage students to think critically about the evaluation of contemporary development policies.

"Students in my econometrics course are pretty skeptical at the start about the relevance of the topic, but I like to show them that these are the tools economists use every day to evaluate policy," says Lucas. "It's the basic idea of using data and econometrics to estimate causal inferences about real-world issues and economic and social policies."

The effect of Lucas' approach is evident. In January 2013, she received recognition from UD's Office of Residence Life and Housing as a faculty member who makes a substantial positive impact on students.

And her students speak highly of her class. Says one, "She opened my eyes to the world around me and allowed me to see many things, especially in the field of economics, in a new light. It is because of her that I am considering a career in Sub-Saharan African development."

Lucas is passionate about helping students think critically about issues of causation and says she hopes her own research not only helps them explore cutting-edge research in economics but paves the way for social and economic improvement in Kenya, Uganda and beyond.

"My goal is to give policymakers empirical evidence to guide a coherent policy that leverages the strengths of different types of schools and pedagogical materials, I guess from the naïve belief that it will make a difference," says Lucas.

But with a clear and positive impact on students, a recent grant to conduct further research, and a growing number of publications reporting findings that show increases in educational access, Lucas' belief is anything but naïve.

UD's Adrienne Lucas recently won a $50,000 grant to conduct research on the cost-effectiveness of raising student achievement in schools in Africa and India. The funding is part of a $300,000 grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation through its Quality of Education in Developing Countries (QEDC) initiative, which provides an opportunity to compare the impacts and cost-effectiveness of six school interventions.

During the past year, Lucas has worked closely with Patrick McEwan of Wellesley College and Maria Perez of the University of Washington to evaluate the overall effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a classroom intervention in Kenya and Uganda. The project examines whether the Reading to Learn Program, which mentored and trained teachers and provided limited classroom resources, can increase the quality of education in both countries.

Schools in the two countries were randomly selected to be either in the "treatment" or "control" groups. All schools received the standard government materials. Additionally, treatment schools were given the intervention. All students in the treatment and control schools were given both a pre- and post-test. Lucas is comparing the test score gains of the treatment students to the control students to assess the effectiveness of the intervention.

Last year, practitioners from Sub-Saharan Africa and India met at a conference organized by Lucas and her team to present preliminary findings from all of the QEDC studies.

The team is now conducting a meta-analysis of all developing country, school-based, primary school interventions that measured an achievement outcome and plan to draw together the disparate studies into a cohesive narrative that will inform future education policy.