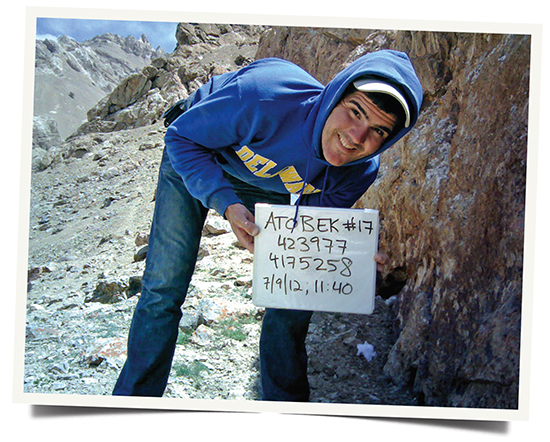

Shannon Kachel tests the camera he just set to ensure proper functioning, and includes the set time, date and coordinates as a backup to his field notes. "Atobek" was the working name he and his colleagues used for the hunting concession study site.

Seattle, Washington

I'm working on an M.S. in Wildlife Ecology.

It involves large carnivores, epic landscapes, exotic cultures, maybe a bit of mountaineering from time to time, and finding workable solutions to seemingly intractable conservation problems—something not unlike my position here at UD.

It's a little bit of a stretch from anything I've ever seen firsthand, but the Saiga antelope of the Central Asian steppes has always captured my imagination. Closer to home, the pronghorn holds a special place in my heart.

Apart from months of agonizing over research methods, triple-checking my packing list, and learning to use the cameras by placing them around White Clay Creek State Park near campus, I spent a lot of time doing cardio intervals and endurance training to prepare for the strains of working at three miles above sea level.

My research took me as high as 17,000 feet above sea level, but I typically slept around 13,000–14,000 feet. As a point of reference, the highest point in the Lower 48 is 14,505 feet.

By day, I spent hours on end hiking ridges and cliff-lines, looking for snow leopard sign. At night, the team and I were fortunate enough to find warm hospitality nearly everywhere we worked. Even when we would arrive in the small hours of the night, local herders were always willing to share a space around the fire in their yurts. Whenever we would visit larger towns to resupply, folks would rent out rooms in their homes and provide a warm meal. When the going got rough in Khorog, I stayed with my local partner's family in a Soviet-era apartment block. We could see army snipers on the surrounding mountainsides keeping watch over the streets. The tension in the air was palpable.

In the Ismaili Muslim tradition, the stranger is revered as a gift from god. Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in the world, yet the hospitality of the people there is unlike anything I've ever encountered. Despite my shortcomings with the languages—locals in my study area spoke a mixture of Tajik, Kyrgyz, Russian, Shugni and Wakhi—I was always made to feel welcomed. I've never felt more open-heartedly embraced in my life.

Shir choi, hands down. A bowl of tea made with yak milk, butter and salt, with chunks of stale flatbread to dip in it—it's the typical Pamiri and Kyrgyz breakfast in Tajikistan. Incidentally, this is the name I've given to one of the big male snow leopards that showed up frequently at my camera sites.

The first time I found snow leopard tracks. I had hiked for miles up an impossibly narrow, steep, ice-filled gorge and stumbled on a beautifully preserved set of pug marks in a rock alcove. The tracks made it real for me, in a way that defies easy description. Suddenly the landscape was full of new potential—suddenly, I saw the snow leopard not as a myth or phantom, but as a living, breathing wild animal.

For this project, my research was limited to Tajikistan, but in reality, the snow leopards that I was studying are part of a regional population that spills over into Kyrgystan, Afghanistan, China and Pakistan, which goes to show that successful conservation in our age of globalization is reliant upon international cooperation.