By Tracey Bryant Office of Communications & Marketing

Flush with fragrant pink phlox and jade-green ferns, mayapples and jack-in-the pulpits, the woodland garden in Annette Giesecke's backyard creates a refreshing retreat, a paradise gained through dedicated weeding and cajoling, the former to keep the forest at bay, and the latter to rein in her rambunctious Irish setters Maia and Kura.

For Giesecke, professor of classics in UD's Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, a garden isn't simply an embellishment to add "curb appeal" or a space for growing tomatoes. Gardens connect us to nature and provide a place for reflection and inspiration. Yet these botanical oases do much more than even that, she says.

"The garden is one means by which humanity tries to find its utopia, its ideal space in nature," Giesecke notes. "I believe that gardens can help humanity move toward a better world."

As Giesecke points out, "utopia" is that ever-shifting horizon toward which human beings are always traveling. Sir Thomas More coined the term, which, derived from the Greek, means both "good place" and "no place," for his book Utopia, published in 1516. The work describes an imaginary island in the Atlantic Ocean with an ideal society. Among their traits, More's Utopians were ardent gardeners who vied to outdo their neighbors.

From the biblical Garden of Eden to New York's Central Park, gardens have been essential to human existence, Giesecke says, but she is concerned that they are becoming undervalued, as humans increasingly distance themselves from nature.

She worries about the residential development she once lived in where the backyards weren't used, and the kids played in the cul-de-sac out front, with each family having its own basketball hoop. When it was time to barbecue, the grills were pulled out onto the macadam driveway rather than onto the lawn.

That's far-removed from the environment Giesecke grew up in, with a mom who was "a really keen gardener," a home in California where it wasn't out of the ordinary to see rattlesnakes in the backyard, and vacation meant camping trips to places like Yosemite National Park with its spectacular mountains and giant sequoia trees.

Giesecke's understanding of the importance of gardens and gardening expanded with her academic training in the classics. She earned her bachelor's degree from UCLA, and her master's and doctoral degrees from Harvard, developing specializations in the areas of Greek and Roman painting, Greek tragedy and Latin epic poetry.

Her studies of ancient wall paintings revealed how much the Romans revered gardens. Roman houses were built around a central courtyard with a garden, and entire walls inside a room would be painted with garden scenes. As a result, the Romans lived entirely immersed in nature.

The House of the Golden Bracelet in Pompeii, Italy, buried by Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D. and unearthed from 1958 through the 1970s, holds some of the most striking examples. Its walls feature intricately painted roses, daisies and poppies, ivy and oleander, sycamore and palm trees. Magpies, barn swallows and numerous other birds are depicted in flight or resting on tree branches and birdbaths.

Recently, Giesecke was invited to present her research as part of a panel on gardens at a conference of the Society for Utopian Studies. As co-panelist Naomi Jacobs, professor and chair of English at the University of Maine, talked about the moral struggle in her garden — of whether to plant ornamentals for beauty, or to plant vegetables to help feed humanity — Giesecke was so moved that she set out to explore the meaning of gardens more deeply.

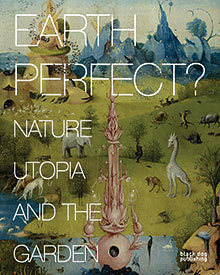

That quest has resulted in the new book EARTH PERFECT? Nature, Utopia, and the Garden, edited by Giesecke and Jacobs. Scheduled for release in May 2012 by Black Dog Publishing in London, the heavily illustrated book includes essays by an international group of scholars and experts from the classics, cultural studies, literature, architecture, art history, horticulture, urban planning, landscape design and philosophy.

For example, environmental artist U We Claus documents his transformation of a former medieval cloister's vineyard in Germany's Odenwald into a work of "sacred" garden art that enables immersion with the natural world.

In an essay structured on the juxtaposition between her gardening practice and the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, organic farmer Susan Willis, a professor of literature at Duke University, ponders how her "island of sustainability" and others like it can matter against a backdrop of massive environmental degradation.

And in his essay, Doug Tallamy, professor and chair of entomology and wildlife ecology at UD, argues that our emphasis on aesthetics in the garden must be replaced by an ecological consciousness that foregoes values of beauty, neatness and control. Instead, he says we should make homes for native plants that can sustain food webs for insects, birds and other creatures — and ultimately for ourselves as well.

UD's Interdisciplinary Humanities Research Center has helped to support Giesecke's work on the book, as well as an extension of it: a four-day symposium to be held at UD in June 2013. The event, co-sponsored by UD, the American Public Gardens Association, Longwood Gardens, and Chanticleer, is aimed at people "who love their gardens and care about the planet" and will discuss issues raised in the book. It also will include tours of nearby public, historic and community gardens.

"What is it about gardens that is important to our imaginations, our psyches, our existence?" Giesecke asks. "It's actually a very complicated concept, and a really, really important thing. If ever there was a time to care about gardens, it's now."