This talk is based on a section of the book I’m writing, Juan

Q. Citizen: Puerto Rican Migrants and the Politics of Citizenship in NYC,

1917-1970. The larger project takes the abstract question of citizenship,

a preoccupation of political and policy history in the last decade, and

turns it into a real analytical problem for social history: what did this

central category of political status mean in everyday life, especially

when that status was as complex and embattled as it was for Puerto Ricans--who

seemed to remain, even as migrants in the metropole, colonial citizens?

Puerto Rico, as you know, was an unincorporated territory of the US after the 1898 war; US Congress conferred citizenship on Puerto Ricans in 1917, as part of a struggle to define the status of the island in relation to the US (this struggle, of course, would continue throughout the 20th c and is still not resolved today). By the end of World War I--partly because of the Jones Act’s citizenship provision, partly because of wartime economy--the beginnings of a Puerto Rican migration began and continued throughout the 20s so that, by 1930, there were 40-50,000 Puerto Ricans in NYC, most by that time living in East Harlem or Brooklyn, downtown or near the Navy yard. Much has been written, by social scientists especially, from

a distance and from various policy perspectives, about these migrants as a “problem” for

the US. In trying to write a social history of Puerto Rican migrants’ citizenship,

I look at how migrants created a “practice of citizenship” that helped to define

their integration in US society and polity. I also explore Puerto Ricans’ expectations

of rights as citizens. But just as important, migrants not only used their citizenship status discursively, as a rallying point to try to mobilize a more focused and activist political culture within the colonia, but also as a category of identity, a place from which to claim rights as citizens of the city and as members of the nation. Though, of course, this idea of membership in the US was complicated by the ambivalence of many Puerto Rican migrants about the political relationship of the island to the US. Nationalist migrants--who were mostly members of the elite until the mid-30s--were defiant about NOT being members of the nation, but wanted to be able to use their citizenship as a tool, a source of leverage to get political backing in the US for the cause of independence. But today I’ll be talking only about how Puerto Rican migrants saw their place as local citizens of New York City, attempting to find a secure place in the city during the Depression. Though Puerto Ricans recognized that they had a certain disadvantage, compared to other immigrants, because they were colonized citizens, many working class migrants sought to use citizenship rights to better their position in what one colonia Democratic boss called the “politics of here”: employment, housing, freedom from discrimination. An essential element of defining who they were in the city, especially in the first two decades of a major Puerto Rican migrant presence there, had to do with race. So, my goal is to show you how Puerto Ricans’ ambiguous racial identity hindered their efforts to secure the kind of protections that US citizenship promised in a moment in which the protections of citizenship articulated by the nation--or at least, by the FDR administration--were dramatically expanding to include not just constitutional rights but also economic and social rights. One of my objectives with this section of the book is to use the Puerto Rican case to probe the limits of liberalism’s broadening definition of US citizenship in this period. I’m interested in how the notion of formal equalities of citizenship relate to the inequalities generated by race. These were, of course, entrenched inequalities that African Americans, especially in the north, were actively challenging by the 1930s. The perception of, and response to, racial inequality was much more complicated for Puerto Rican migrants who were relatively new actors in the black and white racial drama of the urban north. Puerto Ricans struggled to adapt their understanding of race within a broad social field--I actually find the kind of old-fashioned term “social race” useful here--with the growing understanding, by the very beginning of the Depression, that it is a specifically white citizenship that migrants should be striving to attain in the US. My starting point for the chapter of the book that deals with migrants’ evolving racial identity in NYC is a series of public debates on Puerto Ricans and blackness in the early thirties that appeared in the colonia’s newspaper of record, La Prensa, a more or less elite publication that maintained an active “from our readers” pagsome degree of diversity of opinion. The first such debate was inspired by a 1930 New York American article called “Newcomers in the Slums of East Harlem,” on the increased migration of Puerto Ricans to New York since the beginning of the Depression. The article, which characterized the new migrants as “wretched” and “the lowest grade of labor,” “lower than the colored worker,” inspired residents of the Puerto Rican colonia to deluge La Prensa with letters of protest. Members of the community’s Nationalist elite railed against an unwanted citizenship that subjected them to such injustice. La Prensa’s editors printed multiple letters from Maria Mas Pozo, a well-known Nationalist activist, who issued this strident plea:

So an important question is why, exactly, at this moment, would migrants--at least the vocal, politically active migrants--be increasingly concerned about the idea that “they see us as black Americans”, as one La Prensa reader put it in 1931? Clearly migrants’ new anxiety about racial identity and racial prejudice--an issue barely discussed in the colonia in the twenties-- was not just a reaction to a few magazine articles. One part of the answer to the question “Why now?” came from anecdotal evidence of growing prejudice against Puerto Ricans, as the number of migrants grew noticeably in NYC during a period when most other immigrant streams were slowing down or had stopped altogether. It was a prejudice expressed in terms of a conventional US racism in which race is understood in binary terms, so Puerto Ricans must be “black”. Another clue about Puerto Ricans’ evolving racial identity in NYC comes from a different set of sources, ID cards, distributed by a job-placement office created in 1930 by the Puerto Rican Dept. of Labor in conjunction with US officials, which would later come to be called the Migration Division. The objective was to serve the mass of Puerto Rican migrants who arrived in the US jobless, usually, with American citizenship in hand but no passport to prove it. The Identification Office would issue “ID cards” to migrants so that they could prove their American citizenship, and thus garner, they hoped, a slight advantage as they competed with other “foreigners” in the labor market. A key part of identifying applicants was to label their “complexions”. I’ll show you some examples of the applications but first I want to emphasize some key trends in my sample of the compexion labels out of a total of about 30,500 applications between 1930 and 1949. I looked at roughly 1 in 6 of these applications and recorded the complexion labels of each. The first key point is the variation in the labelling terminology--not just “black,” “white,” or “mulatto.” About 15 different labels were used in the 2 decades I looked at, including “brown,” “dark brown,” “light brown,” “ruddy,” “olive,” and “regular”. These were Puerto Rican labels, not North American ones. The second major point is that there were trends in the variations of the labels applied to applicants. Applicants were represented most consistently as “dark” during the thirties--up until about 1938--a time when Puerto Ricans were coming to be seen as an economic and social threat in New York City. Then applicants began to be “lightened” (both by applicants themselves, if they filled in the “complexion” blank, and by employees) during the forties, a period during which a permanent relationship with Puerto Rico--possibly involving statehood for the island--seemed likely, inspiring a discourse in the US about racial lightening and the island’s “vanishing Negro.” More specifically, in this period, no applicants were labelled white, and the number of applicants labelled “light” declined from about 7% in 1930 to 4% in 1938. Then, by 1945, the proportion of applicants labelled “light” had risen to 12%, and a few applicants were given the label “white.” There are no corroborating data now to prove, absolutely, that these shifts reflect social interpretations of race rather than actual trends in the skin color of migrants applying for the ID card, but the sources are most suggestive of a subjective, social interpretation.

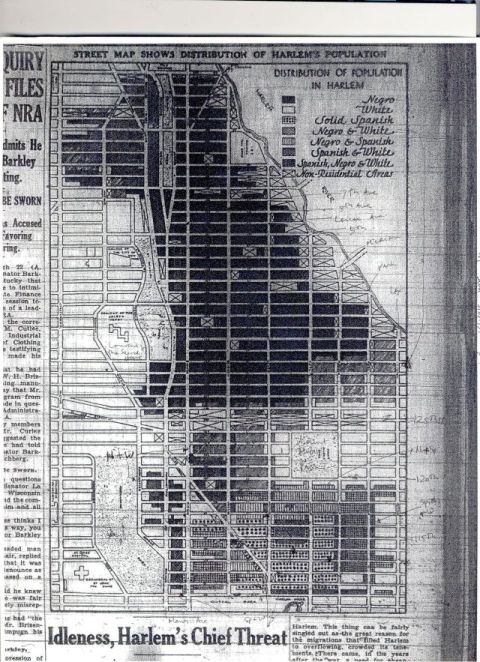

A somewhat obvious point to make about these examples is that they underline Puerto Rican migrants’ uneasy fit in the racial milieu of the United States, and suggest the uneasiness of white America in defining this new nonwhite population. But it wasn’t white Americans who were applying the complexion labels to Puerto Ricans! So we need to consider, also, the role of Puerto Ricans’ own understanding of race defined across a complex social field--race determined by phenotype markers together with class and culture: the employees who made the final decisions about “complextions” were all Puerto Rican, many of them middle class migrants with more education and higher social status--and probably lighter-skinned overall--than the laregly working class clients they served. What investment did the ID office employees have in making sure their job-seeking clients did not think of themselves as “white” as they began their lives in the US? Was this a way that a group who perceived themselves as socially superior could assert some sense of privilege in a city that refused to see the shades of difference between them and their poorer fellow migrants? Or were the ID office employees trying to protect their clients, after a fashion, from the dangers of misconstruing their racial identity as poor, nonwhite newcomers to NY? And then, after nearly a decade on the mainland where normative ideas about race were strictly binary, and at a moment when seeing Puerto Ricans as “white” seemed like a national concern, could the ID office employees have changed their approach to labelling? A problem with this explanation is that it suggests that employees consistently carried out hazy goals of white North Americans’ racial ideology. So, is the “complexion” label primarily a reflection of how Americans (white, but not exclusively) perceived the racial identity of Puerto Rican migrants, or did the label reflect as much, or more importantly, Puerto Rican perceptions of race? There is another question that I can answer more concretely by looking at migrants’ enacting of conflict with their neighbors in the city: What did migrants in general think that their racial identity meant in the context of the mainland, and how did this evolving racialization shape their practice of citizenship as residents of NYC? An answer may be found through the examination of the 1935 Harlem riots in New York--several days of upheaval inspired by the arrest of a Puerto Rican boy who was immediately identified, by the media and by the mostly African American participants in the riots, as simply “Negro.” It was a riot that came to symbolize the plight of African Americans exclusively. How and why did Puerto Rican Harlemites absent themselves, almost entirely, from this “protest against social and legal injustice” that had begun, in the first place, with a Puerto Rican boy? And what did their role in the riots, which took place just blocks from the biggest Puerto Rican migrant neighborhood in the city, say about Puerto Ricans’ perceptions of themselvesas residents, citizens, of the city? In the aftermath, the African American press and city officials in New York agreed that the Harlem riot stemmed from the problems of “Negroes,” and did not concern Puerto Ricans, and many middle-class and elite Puerto Ricans were happy to support that perspective. Just as it treated issues of racial injustice, like lynching, as problems of little concern to Puerto Ricans, La Prensa reported on the rioting in central Harlem in distancing tones, calling the incident “race riots” among the “colored elements of that neighborhood.” The editorial printed two days after the riot offered an explicit warning about the dangers of Puerto Ricans’ being implicated in the riots. “The fact that it was a Puerto Rican boy who was the origin, or excuse, for the noisy disturbances and clashes with the police, could serve as the basis for a new, negative interpretation of…the Hispanic community here,” wrote the editors. They distinguished the “colored” sections of Harlem as characterized by “intense political activity” and “bizarre cults” (a reference to the Church of Father Divine). On the other hand, “entirely separate from this is the Spanish-speaking group of the neighborhood, with distinct problems, absolutely different interests, and ethnic characteristics that disassociate Hispanics from their colored American neighbors.” The editorial closed with a warning that “events and situations created by the other half of the district, not Hispanics” threatened to exacerbate the preexisting antipathy of “the authorities” towards Hispanics. The editors admonished their readers: “You must not ignore the fact that, once again, the discredit and unwanted notoriety generated by non-Hispanic Harlem, falls upon our part of the neighborhood.” La Prensa editors further staked out the social distance

between American blacks and Puerto Ricans by reporting extensively on

the damage done by rioters (presumably African American) to Hispanic-owned

businesses in Harlem, especially those located near the corner of 116th Street

and Lenox Avenue. The paper also gave detailed descriptions of window-breaking

and looting in four stores owned by Hispanics, and damage done to 40 Hispanic-owned

stores. Yet while La Prensa editors were anxious to defend the

distinction between Spanish-speakers and African Americans in Harlem, they

assailed what they referred to as the “racial dividing line” erected by some

black businesses, who “have in their shop windows signs that say ‘colored,’ indicating

that people of the white race are not welcome.” The thinly disguised point

here was that many of the Hispanic residents of Harlem counted themselves as

members of “the white race.” The presentation of this interview advertised La Prensa’s desire to distance Puerto Ricans in general (and Rivera in particular) from the “racial hatred” that “exploded” in Harlem. In describing a woman who had tried to defend Rivera from his accusers, the interviewer had described an “incident with the woman of his [Rivera’s] race”--meaning African American--a comment that reveals something more complex about the perception of difference between Puerto Ricans and African Americans. It suggests that Rivera’s status as a Puerto Rican “of the colored race” did not presuppose any common cause, socially or politically, with an American “of the colored race.” Rivera may have been called “black” by Puerto Ricans and Americans (white or black) alike, but this did not mean that, in the eyes of Puerto Ricans, he had any social kinship with the African American woman who allegedly incited the crowd at the Kress store. One working class La Prensa reader staked out a similar social distance from African Americans in his commentary on the riot, but drawing on the political language of the radical left. Libertad Narváez, who lived on the eastern edge of the area of the rioting, presented a passionate critique of the conditions created in Harlem by the “explotadores capitalistas,” expressing deep sympathy with the plight and the grievances of the rioters.

Narváez defended the alleged role of the Communists

in the riots, asserting that Communists “are the only ones who defend the interests

of the black worker in this country, and the only ones who sincerely represent

and openly support…the highest social, racial, national and political aspirations

of this oppressed race.” His rhetoric can be read, then, as very typical of

Communist discourse on racial egalitarianism--especially that which gained

currency across Harlem in the thirties. Yet many Puerto Rican activists expressed bitter resentment about their absence from the studies and reports about living conditions in Harlem that appeared in the wake of the riots. Mayor LaGuardia, in his first public statement about the riots, made on the following day, promised to appoint a committee of “representative citizens” to study the riot and its causes. But that “representative” Committee turned out to consist only of African Americans and white Americans, despite the fact that Puerto Ricans comprised the majority or plurality of residents on about one quarter of Harlem’s residential blocks and ranked second only to African Americans as the largest national or “ethnic” group in the neighborhood. Puerto Rican activists and leaders of el barrio’s organizations had expected to participate in the discussions about conditions in Harlem. Jesús Flores, head of the working class labor organization Unidad Obrera, wrote to the Mayor’s Committee:

Another letter to the Mayor’s Committee, from the Comité Pro-Puerto Rico, repeated the same message, “So that you may hear the different slights and humiliations to which the Puerto Ricans are subjected, we expect from you, that you allow this Committee, which is composed of more than 60 organizations, Spanish-speaking and in their majority Puerto Rican, to testify.” Other Puerto Rican leaders objected forcefully to the fact that Puerto Ricans were excluded from representation on the Mayor’s Committee. Representatives of two of the more elite colonia organizations wrote to the Mayor several months after the riots to point out what they saw as the injustice of this exclusion. Isabel O’Neill, a Nationalist activist, wrote to the Mayor a harsh indictment of his treatment of Puerto Ricans:

Although, in the end, no Puerto Ricans spoke out publicly as actual participants in the riots, the aftermath of the riots represented a key moment in colonia political culture. Puerto Ricans had seized on the moment surrounding the riots as an opportunity to articulate an evolving language of rights; and in constructing this “rights talk,” the two major factions in the migrant community--the mostly Nationalist elite and the working class left--managed to unite on the question of local conditions and local political representation. Both articulated their rights to “recognition in civic affairs in this city” in similar race-blind language. While African American activists in Harlem sought to link their poverty and social oppression to their racial identity, Puerto Ricans wanted to do the opposite. They wanted access to white citizenship. Even Libertad Narváez, who was probably a Communist

and who railed against the treatment of “black workers,” was careful to talk

about the rioters in the third person. He supported the struggle of “their

race,” but suggested no common cause between “them” and Puerto Ricans. By 1935, Puerto Rican New Yorkers had settled on an ad hoc strategy: Puerto Rican migrants sought to deflect attention away from the question of their racial identity by articulating concerns that were parallel to but not in common with African Americans. In the demands they made of city officials and in staking out their territory in post-riot Harlem, migrants sought--using a nascent language of rights very similar to that of their African American counterparts in Harlem--to disaggregate questions about their racial identity from their rights as Harlem residents and as American citizens. Sociologist Margaret Somers has asserted that “citizenship rights are practices, not ‘things’.” (1) Following Somers’ admonition, my goal in examining (or reexamining) this material is to examine the practices--discourse as well as strategic action--of Puerto Rican migrants as they sought to reconceptualize their identity as American citizens in the face of intensifying racialization in the media--their categorization as “black” in North American terms. In the social history of African Americans and other “minority” groups in the United States, the disconnect between ideal and real forms of citizenship has been quite obvious. To advance our understanding of the meaning of citizenship for actual people then, we have to look not just at what citizenship promised or provided in terms of rights, but at how various groups have articulated their expectations of citizenship rights, using different strategies in different contexts. Puerto Rican migrants in the Depression demanded a de-racialized identity as Americans, hoping to counter the “political and civic indifference and unmindfulness at which we feel aggrieved.” That expectation was not to be born out; but the “end of the story” is only one part of a history of Puerto Ricans’ US citizenship on the mainland. Notes 1. Margaret Somers, “Citizenship and the Place of the Public Sphere: Law, Community, and Political Cutlure in the Transition to Democracy,” American Sociological Review 58 (October 1993): 587-620. Bibliography Archival Sources

Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies, Philadelphia Leonard Covello Papers

Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, New York City

Jesús Colón Papers

Erasmo Vando Papers

Migration Division Records

Costureras Oral History Project Transcripts

Pioneros Oral History Project Transcripts

Municipal Record and Research Center, New York City

Fiorello H. LaGuardia Papers

Works Progress Administration (WPA) Files

Newspapers and Periodicals

Amsterdam News La Prensa New York American New York Herald-Tribune New York Sun New York Times

Books, Articles, and Dissertations Allen, James S. The Negro Question in the United States. New York: International Publishers, 1936. Anderson, Jervis. This Was Harlem: A Cultural Portrait, 1900-1950. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1981. Applebaum, Nancy P., Anne S. Macpherson, and Karin Alejandra Rosemblatt. Race and Nation in Modern Latin America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. Barkan, Elizar. The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States Between the World Wars. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Bunche, Ralph. The Political Status of the Negro in the Age of FDR. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973 [1940]. Cabranes, José. Citizenship and the American Empire: Notes on the Legislative History of the United States Citizenship of Puerto Ricans. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979. Clark, Truman. Puerto Rico and the United States, 1917-1933. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1975. Dalfiume, Richard. “The Forgotten Years of the Negro Revolution.” Journal of American History 60 (June1968): 90-106. Fogelson, Robert, and Richard Rubenstein, eds. The Complete Report of Mayor LaGuardia's Commission on the Harlem Riot of March 19, 1935. New York: Arno Press, 1969. Gordon, Maxine. “Race Patterns and Prejudice in Puerto Rico.” American Sociological Review (1949): 294-301. Graham, Richard, ed. The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870-1940. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990. Greenberg, Cheryl. "Or Does It Explode?" Black Harlem in the Great Depression. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Haney-López, Ian F. White By Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996. Lapp, Michael. “Managing Migration: the Migration Division of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1948-1968.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins, 1991. Lee, Sharon M. “Racial Classification in the U.S. Census, 1890-1990.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 16 (January 1993): 75-95. Martinez-Alier, Verena. Marriage, Class and Colour in Nineteenth Century Cuba: A Study of Racial Attitudes and Sexual Values. London; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1974. McKay, Claude. Harlem: Negro Metropolis. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1968. Moore, Robin. Nationalizing Blackness: Afrocubanismo and Artistic Revolution in Havana, 1920-1940. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997. Mörner, Magnus. Race Mixture in the History of Latin America. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1967. ______. Race and Class in Latin America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. Nobles, Melissa. Shades of Citizenship: Race and the Census in Modern Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000. Rodríguez, Clara E.. Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States. Critical America. Ed. Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. New York: New York University Press, 2000. Rodríguez, Clara E., and Virginia Sánchez-Korrol, eds. Historical Perspectives on Puerto Rican Survival in the U.S. 2nd ed. Princeton: Markus Wiener, 1996 [1980]. Savage, Barbara. Broadcasting Freedom: Radio, War, and the Politics of Race, 1938 1948. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999. Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue, Volume I: The Depression Decade. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981. Skidmore, Thomas. Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974. Wade, Peter. Blackness and Race Mixture: The Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ______. Race and Ethnicity in Latin America. Chicago: Pluto Press, 1997. Wolters, Raymond. Negroes and the Great Depression. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 1970. |

But

it was commentary on race framed absolutely in black and white--even on the

part of a Puerto Rican communist sympathizer! So Narváez’s letter signifies

yet another instance of silence on the place and plight of Puerto Rican migrants

in Harlem, this time from the left. Not only did Narváez fail

to mention that there were large numbers of Puerto Ricans who would identify

themselves (or be identified by others) as “Negro workers”; he also ignored

the fact that Puerto Ricans had been expressing for years the same grievances

as African Americans concerning housing, relief, and discrimination.

But

it was commentary on race framed absolutely in black and white--even on the

part of a Puerto Rican communist sympathizer! So Narváez’s letter signifies

yet another instance of silence on the place and plight of Puerto Rican migrants

in Harlem, this time from the left. Not only did Narváez fail

to mention that there were large numbers of Puerto Ricans who would identify

themselves (or be identified by others) as “Negro workers”; he also ignored

the fact that Puerto Ricans had been expressing for years the same grievances

as African Americans concerning housing, relief, and discrimination.