NSF Career Award

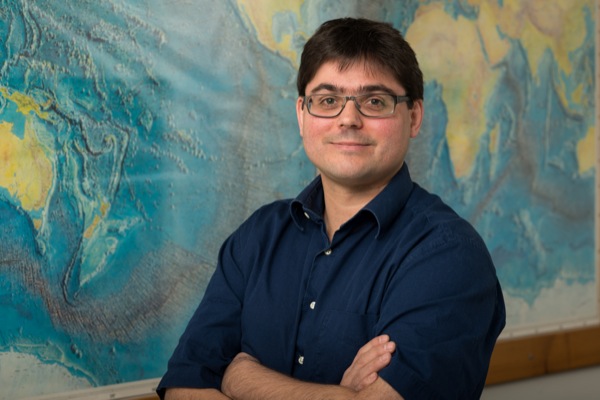

CEOE's Kukulka receives prestigious award for research on upper ocean turbulence

12:56 p.m., March 26, 2014--Picture pouring milk into coffee: Don’t stir, and the milk and coffee combine slowly. Swirl with a spoon, and suddenly the two mix together quickly.

“It’s the same thing with the upper ocean,” said Tobias Kukulka, assistant professor of the physical ocean science and engineering in the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment. “But wind, waves and currents do the mixing.”

Honors Stories

National Medal of Science

Warren Award

Kukulka received a prestigious Faculty Early Career Development Award from the National Science Foundation to investigate upper ocean turbulence and particle transport. His research has implications on the motion of pollutants, plankton, nutrients and air bubbles as they work their way through the seas.

When waves and currents churn water into a series of long, whirling masses, noticeable as bands of bubbles on the sea surface and aligned with the wind, the phenomenon is called Langmuir circulation. These vortices and breaking waves interact, causing water in the upper ocean — roughly the top 30 meters (100 feet) — to mix together.

Kukulka studies those complex processes, taking numerous variables into account, with sophisticated mathematics and computer models (watch a video here). With support from the NSF Career Award, he endeavors to summarize the physics at play in a new method that follows the motion of particles. Then, he will apply his analysis to understanding a major ocean pollutant known as the “great ocean garbage patch.”

When many people hear about a giant garbage patch in the ocean, they picture a massive, floating island of tangled milk jugs, six-pack rings and grocery bags. While that kind of debris certainly causes serious problems for sea life, marine garbage patches are actually made up of millimeter-sized bits of plastic.

The buoyant, degrading plastic pieces are widespread throughout the world’s oceans and congregate in large areas, transported by currents. The specks of litter do not just rest on the surface; they are constantly bobbing up and down in the water with movement caused by wind and waves.

Traditionally, plastic marine debris is measured along the surface where particles presumably float. But kinetic energy from upper ocean mixing could be pushing the plastic below the surface.

“If it’s very turbulent, then these small plastic pieces are actually drawn down and submerged,” Kukulka said. “So potentially, we need to really look into a different approach from just measuring the surface, and this modeling can help.”

The same principles could transfer to other applications and prompt revisiting of ideas on particles trapped in the upper ocean. Oxygen-producing plankton could be getting less sunlight than we think. More carbon dioxide from the air could be entering the water through air bubbles.

Weather and long-term climate models may not accurately be taking into account the exchange of heat between the air and the ocean — models that Kukulka hopes to improve within a few years.

“We need to understand how the wind wraps over the ocean surface,” he said. “Tropical cyclones and hurricanes are driven by air-sea heat fluxes.”

The heat exchange, in turn, depends on surface temperature, which is determined by mixing with cool deep water.

The plastic pollution application tends to resonate most with the public, Kukulka finds, and he will focus on that area for several education and outreach activities through his Career Award. Working with the Sea Education Association (SEA), he plans to create a more effective way to quantify ocean pollution. He or his students intend to lecture on the subject for SEA undergraduate programs, such as the semester at sea.

Kukulka will also develop a lab unit for high school students, bringing a water tank to classrooms that shows upper ocean physics. The unit will be included in Summer Residential Programs, aimed at increasing participation of underrepresented minorities.

His hope is to teach physics and environmental science in engaging ways, while also clearing some misconceptions about marine debris.

“When I start talking about millimeter-sized pieces, it’s a surprise to many people,” he said. “I’m excited to bring the research to all levels, from high school to graduate programs.”

About the professor

Tobias Kukulka studied physics at Freie Universität Berlin in Germany before earning a master of science degree in environmental science and engineering from Oregon Health and Science University.

During his doctoral studies at the University of Rhode Island, he researched the effect of breaking waves on wind and ocean surface waves and finished his Ph.D. in 2006. He then worked as a postdoctoral scholar at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and joined the University of Delaware in 2010.

His research is frequently published in the Journal of Physical Oceanography and Geophysical Research Letters and has attracted media attention from National Public Radio, MSNBC and other major outlets.

Article by Teresa Messmore

Photo by Evan Krape