Poultry in Motion: UD and the poultry health system

OUR FACULTY | Baked, grilled, fried. Sautéed in spinach and cooked in wine. Drenched in sauce. Seared on the barbeque. Of all the ways to eat chicken, perhaps none is more important than the one we probably think of least: Safely.

Poultry is a staple in the global diet, and especially so in America, where the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates the average American consumes 54 pounds each year.

Ensuring a wholesome product from farm to table is critical for public health and for the industry itself.

In fact, no bigger business than poultry exists in Sussex County, Delaware, and elsewhere on the Delmarva Peninsula, where an estimated 560 million birds are produced each year for consumption, contributing more than $5 billion annually to the local (Delaware-Maryland-Virginia) economy.

On the Peninsula, some 1,700 private family farms raise chickens for one of the “Big Five” companies: Allen-Harim, Amick, Mountaire, Perdue and Tyson. On a good day, flock supervisors send tens of thousands of chickens to the processing plant and on to families’ tables. On bad ones, they take sick birds to UD’s “Dr. Dan.”

A juggernaut in production

Surrounded by miles of farmland far from Newark, the Carvel Research and Education Center in Georgetown, Delaware, still has the unmistakable look of UD, as if its Georgian brick façade were lifted off the Green and transported 80 miles south.

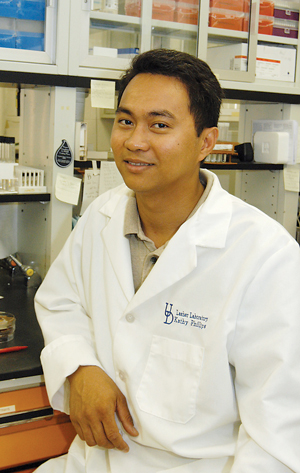

Adjacent to the main building is Lasher Laboratory, named for avian vaccine pioneer Hiram N. Lasher, and here, at the helm of Delaware’s primary poultry health diagnostic center, stands poultry veterinarian Dan Bautista.

As director of Lasher Lab, he is responsible for detecting diseases as soon as possible to differentiate “normal” illnesses like bronchitis from devastating ones like avian influenza (AI), the latter of which carries an almost immediate impact on production and trade.

The high-tech laboratory recently underwent a state-funded $4 million renovation, and it is there that Bautista and his team assess thousands of cases each year, testing the vast majority for AI, as well as checking for bacteria like salmonella, which can cause food-borne illness.

Bautista grew up on a farm in the Philippines, raising crops and livestock like hogs, chickens, cattle. He lived “farm-to-table” before the term was popular, and his basic understanding of veterinary anatomy and physiology helped him during his formal veterinary training.

He attributes his professional trajectory to that of many children who grow up with a firsthand appreciation for agriculture. “It’s the same story with agriculture professionals raised from farm families here in the U.S.,” he says of his reasons for entering the field. “Mine’s just from the other side of the world.”

Bautista worked for a few years as faculty at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of the Philippines, in the mid-1990s, when he began to notice that imported frozen chicken products from the United States were far cheaper than even live birds from local farms. “I remember thinking, ‘Wow. The U.S. must be a juggernaut in poultry production.’”

Individual chickens, after all, are fairly cheap. The way to make money is in volume.

He would soon see the size, efficiency and technological prowess of the global juggernaut that is the U.S. poultry industry and U.S. agriculture as a whole when he enrolled in graduate school and poultry residency at the University of Maryland in 1999, and then worked for the Maryland Department of Agriculture. He joined the UD Lasher Lab in 2006, working to keep Delmarva poultry free from important diseases like avian influenza.

Transmitted through the droppings of waterfowl, which help to spread the virus during annual migration events, AI is considered the most potentially devastating poultry disease.

The Delmarva Peninsula is one of the top-10 broiler producing regions in the country, and the Delaware Bay happens to be one of the biggest stopovers for migratory waterfowl. An ever-present virus in wild birds, avian influenza remains a threat to domestic poultry production.

A perceived risk of AI can lead to trade bans that hit us right in the GDP. Take, for instance, the 2004 outbreak, in which the fast-mutating strain of a global AI killed millions of birds and cost billions worldwide. That year, the Delmarva region survived three cases of low-pathogenic AI—not harsh enough to infect and kill many chickens, though its mere presence led to embargoes of poultry exports and significant losses in earnings.

Lauded internationally, the “Delaware model” combines University research with industry expertise and state and federal partnerships, resulting in fast and accurate diagnostic testing, complemented by fast and aggressive response. It’s a well-honed, highly coordinated system amongst multiple agencies.

“If there’s a fire,” adds Bautista, “we don’t waste a second debating who’s going to put it out.”

And such targeted action doesn’t end with AI.

Samples collected from sick chicken flocks are constantly transported to the UD’s Charles C. Allen Laboratory in Newark, where they undergo further investigation, analysis and study.

“We’re very fortunate,” Bautista says. “We have the eyes and ears into what’s going on in the field, but just as importantly, we have the disease agents to study.”

It’s a powerful combination, and one of immense value to the Delmarva poultry juggernaut.

“Healthy chickens translate to healthy food,” says Bruce Stewart Brown, senior vice president for food safety, quality and live operations at Perdue Farms, which processes around 6 million birds each week in the Delmarva region. “There are some serious diseases that cause significant problems—and change all the time.”

So then how do we combat an ever-changing challenger?

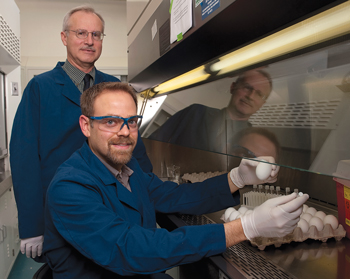

For Jack Gelb, professor and director of the University’s Avian Biosciences Center, and scientist Brian Ladman, the answer is stopping it before it starts.

Feeding a growing population

In 2011, Gelb, ANR74, 76M, and Ladman, ANR97, 01M, BE05M, ANR15PhD, noticed a rather peculiar outbreak of avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a common poultry disease known as “1639,” on three different farms. Each one carried 20-30 percent mortality per flock (as opposed to the 4 percent average). Some 100,000 chickens died—low numbers, relatively speaking—and with time, the disease seemed to go away on its own, as they sometimes do. The researchers carried on, giving it little thought beyond the always-enticing aspect of investigating something new.

The “Delaware model”

Then, in 2014, “it was like jailbreak,” as the disease resurged and was found throughout the Peninsula. More than 100 cases were reported, with nearly half a million chickens affected throughout the region. The disease represented an animal welfare issue as well as an economic one.

In Newark, at UD’s Allen Lab, both Gelb and Ladman helped develop an experimental vaccine at the request of the poultry industry. In 2016, one of the most affected companies began using the vaccine in all of their Delmarva flocks—and have witnessed a marked reduction in outbreaks.

“We’re not just talking about farming chickens, we’re talking about growing food,” says Gelb. “Any threat to that system impacts us all.”

And Gelb means “all” in the literal sense. One of the great advances of our time, he says, is feeding a growing population with affordable products, while respecting animals and raising them safely.

For Bautista, who immigrated here nearly two decades ago, the United States is a leader in this endeavor.

“I feel like I joined a winning team,” he says of the American poultry system. “We’re thinking more globally; we’re thinking in terms of safety and health, with the belief that by constantly safeguarding the production of wholesome, locally grown chickens, we can have a major and meaningful impact on human health and safety. Because at the end of the day, it’s a trust issue: ‘Would I feed this to my kids?’ That’s the ultimate question, right? And I would. I do.”