A special edition of the recurring Messenger feature, My UD

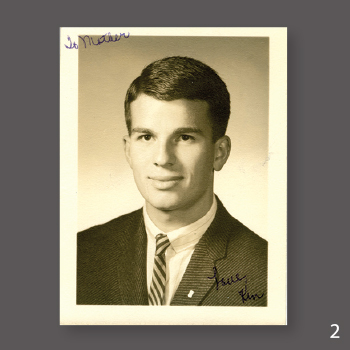

by Ken Adams, AS11, 16M

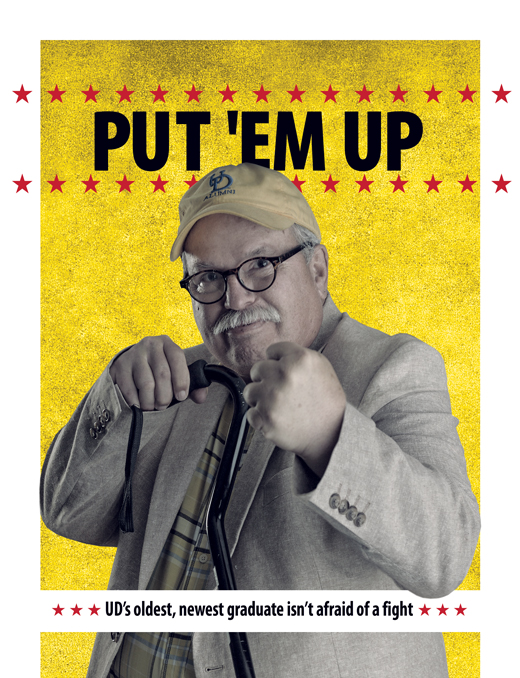

ALUMNI & FRIENDS | They say that fighting never resolves anything. I say it depends on what you’re fighting against.

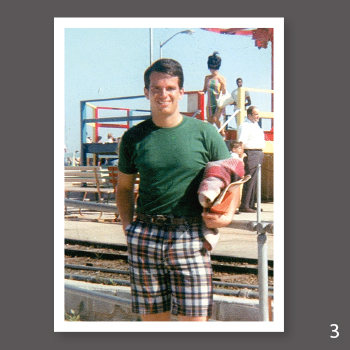

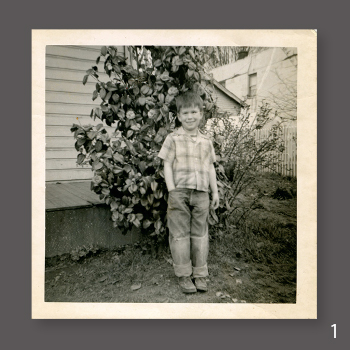

In life, not fighting is sometimes not an option. It’s not an option if you’re a bullied kid in a tough California steel town, as I was some six decades ago. It’s not something that could be avoided by a young, gay man such as myself trying to live without apology or shame during a distinctly unenlightened time in America.

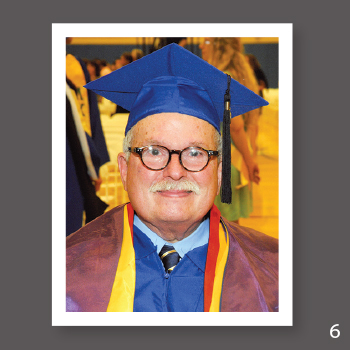

And a fighting spirit certainly helped forge the late-blooming scholar I would become when I enrolled as an undergraduate at UD in 2007, at age 61, surrounded by students a fraction of my age and bombarded by coursework that few near-retirees would care to digest, all while battling Parkinson’s and heart disease.

Through my 70 years, I have believed that to abandon a sense of contentiousness and a willingness to question the status quo is to abandon the very principles that make us capable of fulfilling our potential. To protect and preserve his power as an individual—to remain a thinking, growing human who is capable of seeing injustices, and committed to making it right—a man must not fail to speak out when it’s needed, and a university needs to be a place that instills the courage to do so.

In many ways, UD would become that place, giving me the tools to continue fighting those “good fights,” in places far from Newark, among children truly in need of a champion. In other ways, UD was the kind of place that would itself fire up my fighting instinct from time to time—especially whenever I sensed a threat to the open debate of ideas that should be sacrosanct on any campus.

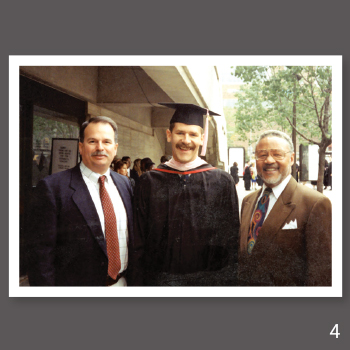

This University was a place where I would: earn a bachelor’s degree in political science (with a minor in women’s studies) and a Master of Arts in Liberal Studies; receive the Raymond A. Callahan Prize and gain acceptance to the Dean’s Scholar Program; hear my name hailed in a university president’s commencement address; and be inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi honor societies.

But to me, my real successes at UD aren’t wholly defined by grades or degrees, and the true worth of the UD experience is about far more than convocation honors and gilt-edged certificates. Achievement means nothing without impact. Ability matters little if it’s not applied. Ambitions are irrelevant if they are not pursued.

That’s true when you’re 18, and still true if you were a 60-something like me who had a nagging need to get the degree that had proved elusive for so long, put on hold by lack of funds and a long career in an assortment of professions, from sales and marketing, to college recruiting, to Wall Street. For me, the drive remained alive, and the flame still flickered within, fanned ever brighter during my years at UD by many brilliant, giving, truly inspired professors—men and women who encouraged me to think, to question, to be an agent of change in a justice-hungry world.

And so I fought. I fought when I won a chance to conduct research in Romania through the Dean’s Scholar Program and the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program, which give students like me the power to design their own curriculum to suit their intellectual interests and passions. For me, that freedom meant a chance to throw some light onto the social injustices I had seen in Romania, where judicial corruption, sex-trafficking of orphans and discrimination against the Roma ethnic group are persistent evils in an otherwise beautiful culture.

I fought whenever I sensed my left-leaning professors veering too closely to a political lockstep on a variety of issues, reminding them of their essential role in fostering individual critical thought among students, and cautioning them against rewarding only the students who parroted their ideological line.

I fought against the limits of my own aging body—against the heart disease and Parkinson’s that means typing with just one finger of one hand, and a cane or wheelchair to get from class to class.

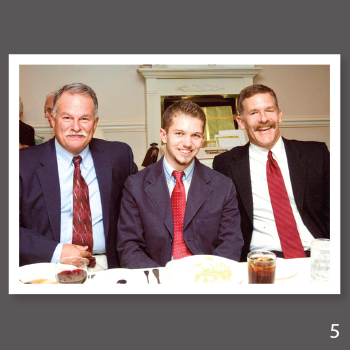

And, as with most of life’s struggles, I would eventually find that past all pain, rewards frequently await. I look at the Romanian orphanages that I have worked to help during my 18 trips to that country, and see they are in better places now. I look at the partner who helps care for me—UD music Prof. John David Smith—and I see all that can be done when done together, through love, with devotion.

I look into the eyes of our adopted son James, and I remember the days when he was a frightened young student at Louisiana Tech who called a crisis clinic in panic after his parents had thrown him out because he was gay.

I answered that call. Along with my partner John, we would become this bright young man’s friends, then his protectors, and now his adoptive parents. In him I now see few traces of the scared boy who would become a man—and a fellow UD graduate—ready to fight his own fights and pursue his own passions.

This is the message we must give to our young, to the next generation of changers, doers, solvers. I look at the many students with disabilities whom I have volunteered to help at UD’s Assistive Technology Center during my years here, and I want to tell them:

Be sure to embrace the lesson I was taught through my years of living, and my time at UD. Keep fighting, no matter who or what you’re fighting for. Don’t despair if you don’t always prevail, because no one really loses until they stop trying to win.