ALUMNI | Shaun Gallagher, AS02, was putting his young son back to bed in the middle of the night when he had one of those fleeting thoughts that can seem brilliant to the sleep-deprived: Maybe he could write a book that would encourage other parents to learn about child development by using their own babies and toddlers as research subjects.

“I knew my mind was just wandering when I came up with this at 3 a.m.,” Gallagher says. “But in the morning, it still seemed like a good idea.”

He talked it over with his wife, Tanya Gallagher, AS04, who at the time was expecting their second child, and the two decided the idea was worth pursuing. With a background in journalism and a lifelong interest in science, Shaun Gallagher figured he could base the book on academic experiments conducted by child-development researchers but also make that work understandable, accessible and fun for parents.

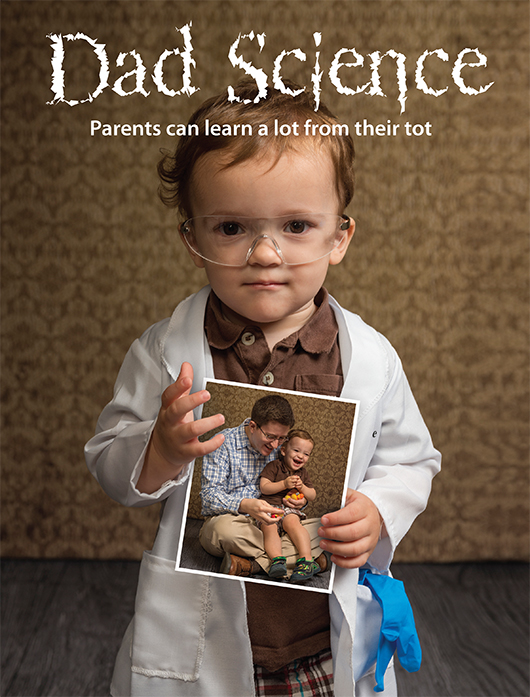

After teaching himself how to locate a literary agent and write a book proposal, Gallagher successfully found a market for Experimenting With Babies: 50 Amazing Science Project You Can Perform on Your Kid, published in October by Perigee, a division of Penguin Books.

When people see the title, he says, they often get the wrong idea, envisioning children being subjected to dangerous experiments or parents becoming anxious about their child’s rate of development. In contrast, Gallagher says he wrote the book specifically to avoid both of those negative scenarios.

“The word ‘experiment’ might sound scary or dangerous, but when you look at the research that child development experts actually do with babies, it’s totally different,” he says. “And I intentionally stayed away from any experiment that I thought parents would use to see if their child ‘measured up’ in some way.

“This book is not an IQ test. This is a way for you as a parent to have fun with your kid—and learn a little about child development while you’re doing it.”

The experiments in the book include one that demonstrates the so-called stepping reflex. Parents who try out this experiment at different times during their child’s first year of life will see how the reflex is present in early infancy, then fades away and later returns when the baby is ready to walk. Other experiments show how babies develop different preferences in reaching for objects and ways in which they follow a parent’s lead in choosing a toy, for example, or trying a new food.

The experiments are labeled according to the simplicity or complexity of duplicating them, the appropriate age of the child involved and the area of research, such as cognitive development, motor skills or language development. In all cases, Gallagher used the underlying academic research as his starting point.

“My background isn’t in child development or psychology; it’s in journalism,” he says. “I feel much more comfortable telling readers what other people—the actual experts—do and what they find. So the academic studies are the anchor of the book.”

Gallagher now is a software engineer for a company that works with online retailers, and his previous jobs in journalism involved some programming and database research, but he never wanted to give up writing. The book, he says, is his outlet—and not the only one.

When Perigee offered to publish Experimenting With Babies, the company also took a look at a website Gallagher founded, www.correlated.org, that surveys readers and then links apparently—some would say, hilariously—unrelated facts and opinions. (Sample: 51 percent of people have attended a wedding where they didn’t think the marriage would last. But among those who own a telescope or binoculars, 70 percent have attended such a wedding.)

The publisher offered Gallagher a two-book deal, and his book about correlations is scheduled to come out next summer.

The Gallaghers, whose family now includes two boys, decided to celebrate parenthood along with Shaun’s writing success. They are donating 15 percent of the Experimenting With Babies royalties to Show Hope, a nonprofit that supports orphaned children and adoptive families.

“We feel that Show Hope is a worthy cause,” Shaun Gallagher says, “and it dovetails nicely with the book, which also is about the bond between parents and children.”

Article by Ann Manser, AS73