No salt? No problem

Cloves, the dried flower buds of a tree native to Indonesia, offer a number of health benefits, including anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Cinnamon, which comes from the inner bark of a tropical evergreen tree, is a natural way to control blood sugar. Saffron, harvested by hand from the stamen of the crocus plant, is one of the world’s most expensive spices.

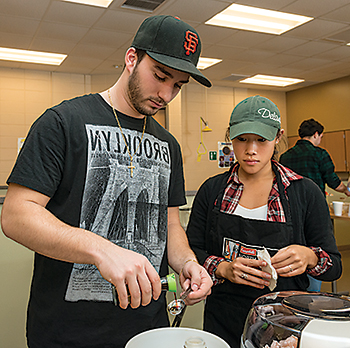

These were just a few of the facts offered by instructor Laura Masullo during week seven of “The Spice Kitchen: Taste the Flavor,” a new one-credit course offered last spring at UD. Masullo, who completed her master’s degree in nutrition in May, tosses up ingredients and tosses out spice trivia as she teaches students how to make “flavorful swaps” by substituting spices for salt in daily food preparation.

During the week in which cloves took center stage, the students learned how to make braised lentils, spiced saffron jasmine rice and autumn apple brew. The recipes are all prepared using methods that reduce fat as well as sodium.

The brainchild of Marie Kuczmarski, professor of behavioral health and nutrition, the course is aimed at helping people become more knowledgeable about spices and their potential health benefits.

“Current dietary guidelines emphasize the need to reduce dietary sodium for better health,” Kuczmarski says. “But if you’re going to take out the salt, you’d better add some flavor to your food in other ways.”

If nutrition and dietetics students learn how to prepare such dishes, the expectation is that they will pass those healthy cooking techniques along to their future clients.

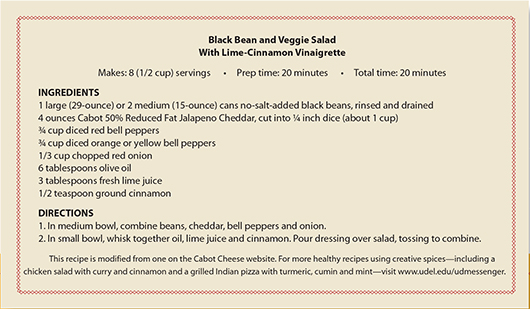

Black Bean and Veggie Salad

Curried Chicken Salad

Grilled Indian Spiced Flatbread Pizza with Tomatoes and Goat Cheese

Summer Squash Sauté

“While registered dietitians are well aware of the need to reduce dietary sodium, they’re not necessarily culinary connoisseurs,” Kuczmarski says. “I think it’s important that we not only advise people to cut back on salt but also provide them with specific ways to do that without sacrificing taste.”

The course was first taught in fall 2011 in the departmental food lab, which has six cooking stations and is equipped with a mirrored demonstration table. The 14-week class consists of four presentations and 10 spice labs, with different students given the opportunity for hands-on cooking experience each week.

Kuczmarski and graduate student Elisabeth Jones conducted a detailed evaluation of the course on a sample of 18 students during its inaugural semester and reported their results in a paper published in Creative Education in 2012.

Their overall conclusion? A culinary class focused on spices can enable college students to learn approaches to healthy, flavorful cooking.

“Most of us are aware that food consumed in restaurants typically contains more sodium, fat and calories than home-cooked dishes,” Kuczmarski says. “However, many people, especially young adults, have limited knowledge and experience cooking with a wide variety of foods as well as with herbs and spices. Courses like this can go a long way toward bringing people back into the kitchen, where they can prepare their own food in healthier ways.”

Article by Diane Kukich, AS73, 84M