Marine scientists take research to extremes

RESEARCH | A UD-led research team set sail on the Pacific in November for an expedition in which several scientists plunged deep into the sea to study environments that included scalding heat, high pressure, toxic chemicals and total darkness. And, just to make “Extreme 2008: A Deep-Sea Adventure” even more exciting, the researchers took thousands of schoolchildren along with them.

The young students from more than 350 schools around the world actually remained on dry land, using technology to join the National Science Foundation-funded voyage on a virtual field trip.

As the scientists worked at sea, they were connected to students through an interactive Web site, where blogs, dive logs, video clips, photos and interviews were posted daily. The students also wrote to the scientists, designed some of their own experiments and participated in a virtual science fair. A capstone experience for selected schools was a “Phone Call to the Deep,” linking their classrooms with researchers working live in the submersible Alvin on the seafloor.

The three-week expedition, led by Craig Cary, professor of marine biosciences in the College of Marine and Earth Studies, left Nov. 10 aboard the research ship Atlantis from a port in Manzanillo, Mexico. Team members—researchers and graduate students—were from UD, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the J. Craig Venter Institute and the universities of Colorado, North Carolina, Southern California and Waikato, New Zealand.

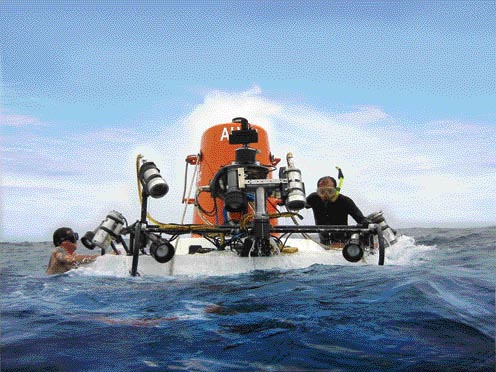

Scientists conducted research on hydrothermal vents at two deep-sea hot spots, where they took the submersible Alvin down from one to nearly two miles below the surface. Built to withstand crushing pressures and to pierce the utter blackness of the deep, Alvin let the scientists observe life around the steaming vents and collect samples for analysis. Both Atlantis and Alvin are owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The scientists’ focus was marine viruses and other tiny life forms called protists. These organisms prey on bacteria, the primary food for vent dwellers ranging from ghost-white vent crabs to bizarre-looking tubeworms.

Eric Wommack, an associate professor with joint appointments in the colleges of Agriculture and Natural Resources and of Marine and Earth Studies, joined Cary in leading the UD contingent. Based at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute, Wommack is an expert on marine viruses and deployed specialized equipment to capture them for analysis in the shipboard lab.

Young students participating in the virtual field trip relayed numerous questions about hydrothermal vents, sea creatures and the researchers’ living and working conditions. Here is a small sampling; for more about the trip, visit www.expeditions.udel.edu/extreme08.

Q: What are hydrothermal vents?—Jazmin, California

A: Hydrothermal vents are cracks in the land or ocean floors where geothermal, intensely hot water spouts out. These vents are most often located at or near volcanic sites and where the tectonic plates are spreading. Most people think of the vents as only being under the ocean, but a more famous one exists on land at Yellowstone National Park.—Bekki Helton, MS ’07 PhD, UD postdoctoral researcher

Q: Why do you think the animals in the depths of the ocean can sustain that amount of pressure and humans can’t?—Andrea, Missouri

A: I think it’s interesting that some of the microbes we bring up to the surface can survive the pressure change without any trouble. The change in temperature is usually more difficult for them to handle, and many of them die if we don’t keep them cold. The larger animals that live at the vent sites usually can’t survive the change to atmospheric pressure, probably for the same reason that we can’t survive at high pressures. Both people and hydrothermal vent animals are composed mostly of water, and our organs are made to pump fluids (blood, for example) that are under a certain pressure. If the outside pressure changes, our organs simply aren’t able to work properly.—Kathy Coyne, UD assistant professor of marine and Earth studies

Q: With all the chemicals in the water near the hydrothermal vents, how is it possible for organisms to exist there?—Carly, New Jersey

A: In nature, one organism’s poison is often another organism’s food. This is exactly the case at the deep-sea vents. Most organisms living in non-extreme environments would not be able to survive surrounded by toxic substances like hydrogen sulfide. The organisms living near the vents have evolved tolerance to these chemicals.—Shawn Polson, UD postdoctoral researcher

Q: What is it like on Alvin?—Jovanni, North Carolina

A: Small, cold and wet, but very cool. The nine-hour dive goes by soooo fast you hardly believe you have been in there that long. Most of the time we are working so hard that we forget to even eat or drink. I have been down over 50 times, but every time is equally as exciting and rewarding.—Craig Cary

Q: What one word would you use to explain what you see in the deep sea?—Alex, Missouri

A: AWESOME!!—Kathy Coyne

For more on research at the University of Delaware, visit www.udel.edu/research.