Richard Heck's legacy

Chemist Melanie Sanford delivers lecture honoring UD Nobel laureate

1:51 p.m., Nov. 17, 2015--The last time Melanie Sanford, a chemist who has won numerous awards for her groundbreaking work in organic synthesis, was on the University of Delaware campus was in 2011, when she spoke at a scientific symposium honoring Nobel laureate Richard Heck, then the Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UD.

On Wednesday, Nov. 11, Sanford again spoke at the University. This time, she received the Richard F. Heck Award and delivered the 12th annual Heck Lecture — the first such lecture since Prof. Heck’s death in October.

Honors Stories

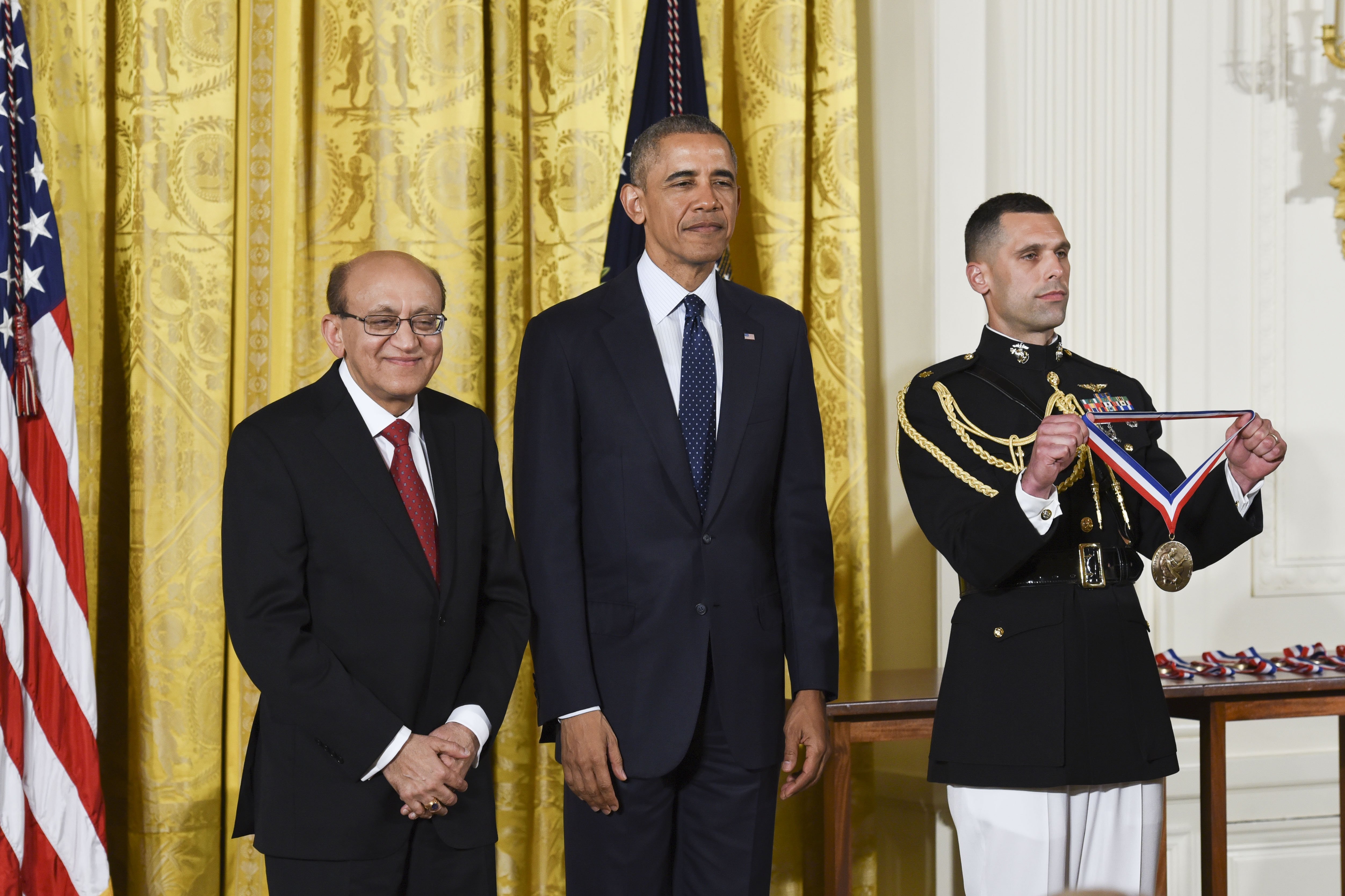

National Medal of Science

Warren Award

“I had the honor to be here the last time Prof. Heck was here,” Sanford told the audience of faculty and students in Brown Laboratory. “And it’s great to be back here today in his honor.”

In introducing Sanford, Mary Watson, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UD, described her research as “revolutionary” and said that, like so many organic chemists, “Her work continues the legacy of Prof. Heck.”

The inaugural lecture in the series, established in 2004, was delivered by Richard Heck himself, Watson noted. She called the 2015 occasion “a special time for all of us to remember Prof. Heck” and said he has been a role model for herself and others.

Sanford is the Moses Gomberg Collegiate Professor of Chemistry and the Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Chemistry at the University of Michigan. Her research focuses on the development of metal-catalyzed carbon-hydrogen functionalization reactions, which have exciting implications for revolutionizing the way that chemists construct a wide variety of important molecules.

In her lecture at UD, Sanford described a number of promising approaches her research group has been taking in its work with aliphatic amines. The importance of those compounds can be seen, she said, by how commonly they are found in pharmaceuticals — including such familiar names as Abilify, Ritalin, Plavix and Januvia — that are taken by millions of people.

Her research group is exploring strategies that, ultimately, would allow scientists to convert a pharmaceutical into a number of derivatives. She described promising approaches using palladium, platinum and iron in catalysis.

Her work has been recognized with many awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship — the so-called “genius grant” — and the Sackler Prize in Chemistry.It has had an impact on how chemists make molecules and also on how they think about the fundamental reactivity of transition metals with organic molecules.

“Melanie Sanford is a chemist reviving and enhancing approaches to organic synthesis previously set aside because of their technical difficulty,” the MacArthur Foundation said in announcing her fellowship in 2011. “Her research focuses on using metal-based agents, primarily palladium, to catalyze reactions that substitute hydrogen in carbon-hydrogen bonds with other atoms or functional groups.

“Through her basic research on organometallic synthesis strategies, Sanford is opening new paths to making important compounds we use every day.”

Prof. Heck received the 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his seminal contributions in palladium-catalyzed cross couplings and other transition metal-catalyzed transformations. The Heck Reaction, as it came to be known, uses the metal palladium as a catalyst to get carbon atoms to link up. His work also spurred a new field of organometallic chemistry, bringing together organic and metal chemists.

Today, the Heck Reaction is one of the most important, fundamental reactions taught to chemistry students and used by industry. It has had a transformative impact in such areas as pharmaceutical development, electronics manufacture, innovative energy technologies, DNA sequencing and disease research.

More about the Heck Lecture and Award

Prof. Heck was a member of the UD faculty from 1971 until his retirement in 1989. He led a highly productive research program and taught graduate and undergraduate students.

The Heck Lecture was created to honor his contributions and to recognize visionary leadership in the field of organometallic chemistry. Lecturers have included three who are now Nobel laureates, six who are members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and five who are members of the National Academy of the Sciences.

A display in the lobby of Brown Lab recognizes Prof. Heck and the late Daniel Nathans, a Class of 1950 UD alumnus who received the 1978 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Nathans’ work with DNA ushered in the field of molecular genetics and laid the groundwork for the mapping of the human genome.

Article by Ann Manser

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson