'Growing Business'

New book looks at economic recovery and job creation in Delaware

2:51 p.m., Feb. 17, 2016--The Great Recession, which lasted in Delaware from 2008 to 2014, hit the First State particularly hard.

The period also saw the disappearance of major employers including Chrysler, General Motors, and Avon. DuPont cut many jobs and the sale of MBNA to the Bank of America also resulted in significant job losses.

People Stories

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

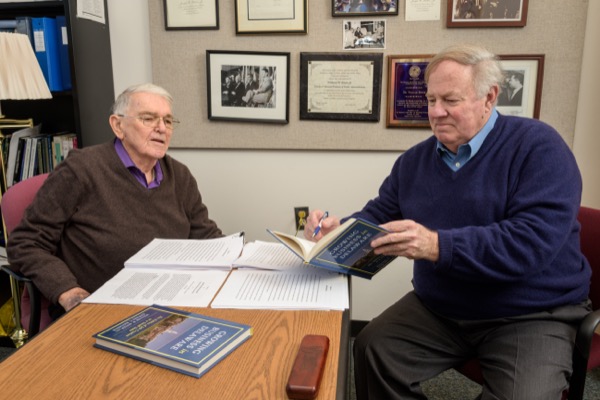

Dealing with these setbacks while trying to attract and keep companies and the jobs they bring is the subject of a new book by two University of Delaware authors.

Growing Business in Delaware: The Politics of Job Creation in a Small State, by William W. Boyer, Charles Polk Messick Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations, and Edward C. Ratledge, director of the Center for Applied Demography and Survey Research, examines the responses from Delaware policymakers and business leaders in addressing these challenges.

Published by the University of Delaware Press, the book is the fourth in the authors’ series about public affairs in Delaware.

In their introduction, the authors recount the cooperation between Gov. Pete du Pont (1977-85) and the General Assembly following a series of adverse business-related events in the 1970s. This collaboration allowed Delaware to adopt a more proactive management approach to economic development.

What followed was a series of economic development initiatives leading to the creation of the Delaware Development Office in 1981, which later became the Delaware Economic Development Office. This gave the First State a nationally unique proactive state management agency for economic development.

During an interview with the authors, Ratledge said that the economic growth measures initiated under du Pont have worked pretty well over time.

“The number of financial industry jobs went from 5,000 to nearly 50,000 today,” Ratledge said. “We now have Bank of America, Capital One and J.P. Morgan Chase, among others. Additionally, J.P. Morgan Chase purchased the south campus of Astra-Zeneca’s Fairfax location for $44 million. The site will eventually house more than 1,000 employees.”

Each of the following six chapters provide an in-depth analysis of a prominent recipient awarded state funding to create jobs, with Chapter One focusing on the rise and decline of Astra-Zeneca.

The next major job growth strategy provided by the state following the 1981 enactment of the Financial Center Development Act involved the Astra-Zeneca pharmaceutical company, the authors said.

Delaware offered a package of incentives that included $18.7 million in cash grants and land, about $79 million in roadwork, $30 million in tax credits, plus training, infrastructure and other perks. This became the most expensive package Delaware had ever offered to keep a company in the state, the authors noted.

While the company employed nearly 5,000 workers at its Delaware locations, a series of legal setbacks, loss of patent protection and corporate acquisitions saw the loss of 550 research jobs in 2010 and another 400 in 2011.

Other chapters focus on Delaware’s port, Wilmington’s Riverfront, Fisker Automotive, Bloom Energy and the Delaware City refinery, while looking at the wide variety of grants, efforts to grow business by other means, and the politics of economic development.

“The state has had some successes and some failures,” Boyer said. “Markets change over time, and the ways companies have to do business changes, too.

Boyer also noted that while some ventures resulted in failures, like establishing Fisker Automotive at the site of the former General Motors Boxwood auto assembly plant, success stories include Wilmington’s Riverfront and the Delaware City refinery.

While the Wilmington Riverfront eventually became an economic development story, it also was an extremely compelling example of brownfield redevelopment, the authors note.

The economic benefits would have been difficult to realize without the considerable remediation work required and the partnerships between businesses, contractors and state and city governments.

“The Wilmington Riverfront project is already solvent,” Boyer said. “The companies that do business there pay taxes, the brownfields are cleaned up and there are hotels and entertainment venues there, as well.”

The politics of job creation, the authors note, involve many factions, each of which thinks their cause and interest are the most important.

“They all think the money should go to them, and they all want to have their own way,” Ratledge said. “At the end of the day, politics permeates everything, including job creation.”

Ratledge also noted that Delaware’s economy is moving away from big companies like DuPont. Changing technology and foreign competition have also resulted in the loss of manufacturing jobs locally and nationally, he added.

“The middle management in companies has disappeared because of computers, and a lot of manufacturing jobs have left, and they are not coming back,” Ratledge said. “It’s a very complex business.”

Although hit particularly hard by the Great Recession, Delaware’s fiscal condition is pretty good, and debt is not a controlling thing as is the case elsewhere, Boyer said.

In the concluding chapter, “Lessons Learned,” the authors note that governments employ two basic strategies to increase economic development and employment.

The first strategy calls for improving the overall attractiveness of their jurisdictions as places to operate by improving the education and skill levels of the workforce, as well as providing adequate infrastructure and a good quality of life for employers and employees alike.

The second strategy, one pursued by Delaware, involves offering firms specific awards, such as cash grants and loans, and, according to the situation, providing favorable tax abatements and rates and enacting legislation favorable to a business. This approach also involves making available free or low-cost worker training, donating a desirable worksite, or reducing some specific cost of doing business, such as subsidizing energy.

The major lessons, the authors conclude, is that due diligence before employing this strategy is necessary, something that has not always been done, and remembering that businesses are always subject to changing markets.

“Job creation will always be with us, and competing with large states with more money is especially challenging,” Boyer said. “When you factor in politics, it becomes a very complicated issue. Delaware wants to be seen as business friendly, and this is something it can do.“

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photo by Evan Krape