Chemical detection

UD laboratory works with Army to detect dangerous chemicals

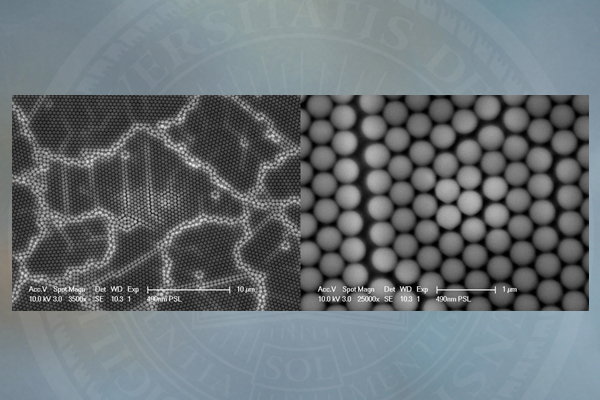

8:59 a.m., Jan. 14, 2015--Led by Mark Mirotznik, the Electromagnetic Materials Laboratory at the University of Delaware is working with the Army Research Office to engineer nanoplasmonic surfaces — materials structured at the atomic scale to interact with light in unusual, specific ways.

Such structures could, for example, help detect dangerous biochemical compounds by changing color if contaminated. “If you monitor what gets reflected back [using a laser], you can detect that a certain chemical is present, even at a distance,” says Mirotznik, UD professor of electrical and computer engineering. In the future, the military could use these materials — scattered over a wide area — to check for substances like anthrax or TNT.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

“We’re using nanotechnologies to engineer tiny little metal patterns at optical wavelengths,” says Mirotznik. “A human hair is about 50 microns across. We’re working on a scale hundreds of times smaller than that.”

By patterning the nanoscale structure, these researchers in effect “dye” surfaces, giving them specific optical properties. “We can design patterns so that if it’s hit by white light, only one of the colors — say, blue — gets absorbed; the rest are reflected away.”

The potential for nanoplasmonic surfaces has also captured the imagination of U.S. Army officials who see a potential application for calibrating military equipment. High-tech sensors can, for example, allow the Army to analyze the chemical contents of a smoke plume just by looking at reflected light.

Calibrating these sensors requires a substance with known, constant optical properties. The colors of many substances change with time and context, but the way a nanoplasmonic surface reflects light is directly and precisely built into its structure.

Aside from providing funding, “some of the Army scientists are so interested in the work that they’re coming over here and working with us.”

Researchers from the nearby U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center visit regularly to work with Mirotznik and his students. “That sort of interaction makes it really interesting,” Mirotznik notes. “I’m having a lot of fun.”