NSF Career Award

NSF award supports Cirillo's research on improving high school math instruction

12:43 p.m., Feb. 9, 2015--Developing proofs is an essential mathematical process that students should learn in high school classes in order to move on to higher levels of math, according to the University of Delaware’s Michelle Cirillo.

But too often, she says, students don’t understand it — making their transition to college-level math classes particularly difficult.

Honors Stories

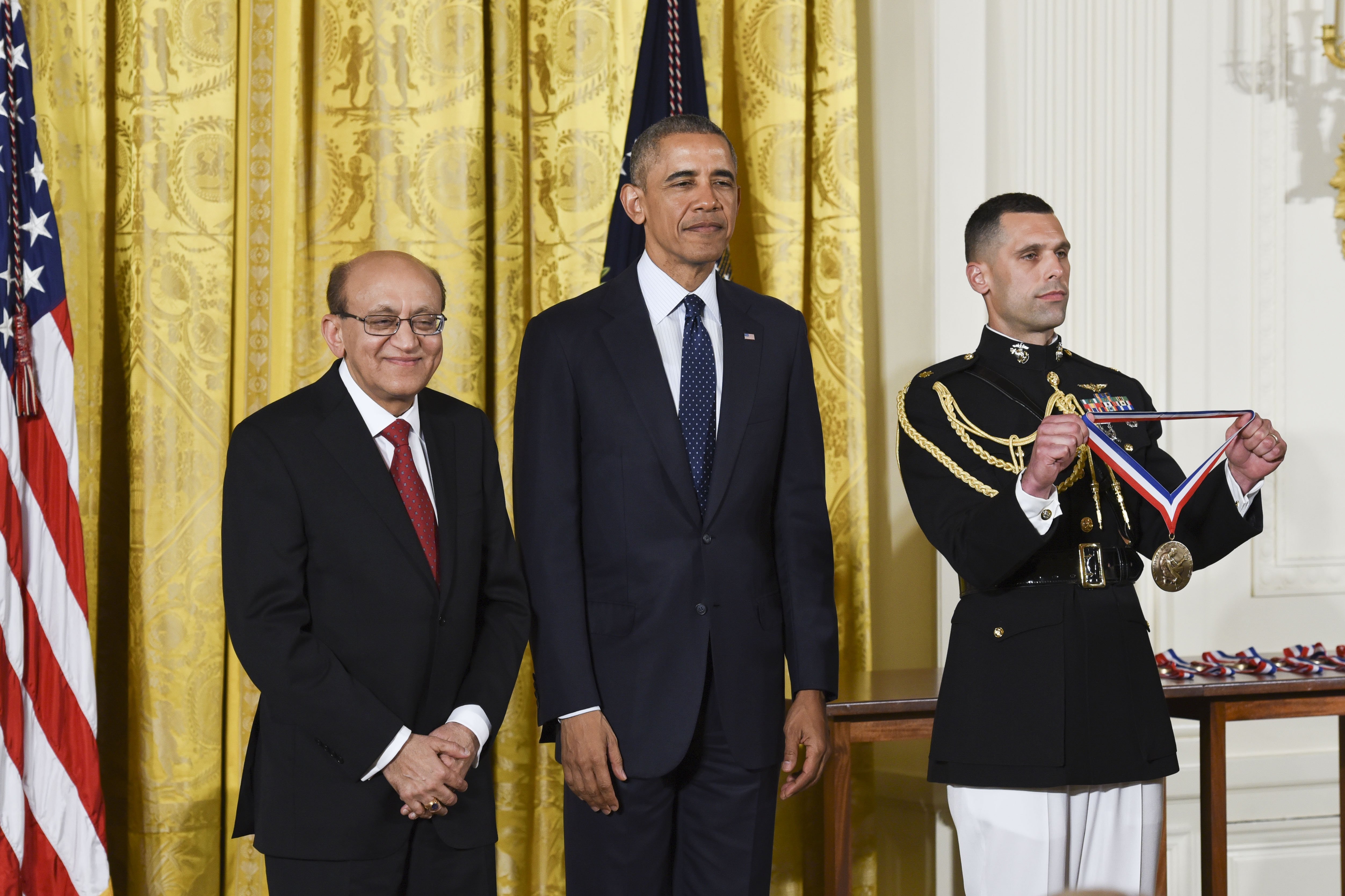

National Medal of Science

Warren Award

“Proof is a central mathematical process and really is the gateway to higher math,” said Cirillo, an assistant professor of mathematical sciences who has been awarded a prestigious national grant supporting her research to find better ways to teach the skill. “But many people have found that proof is one of the most challenging concepts for students to learn and for teachers to teach.”

The National Science Foundation (NSF) recently selected Cirillo to receive a Faculty Early Career Development Award as she works to help high school teachers and students improve the process. The $874,000 grant, “Proof in Secondary Classrooms: Decomposing a Central Mathematical Practice,” will support her research and education program for the next five years.

The highly competitive NSF awards recognize junior faculty for their role as teacher-scholars and are given to those scientists and engineers considered most likely to become the academic leaders of the 21st century.

Cirillo, a former high school math teacher who now prepares prospective teachers through the College of Arts and Sciences’ Secondary Teacher Education program, said her research led her to develop a possible intervention to improve teaching the proof process in the context of geometry. She tried it out in a small, exploratory study with good results.

“I wanted to show that if you teach proof in a different way, students can be successful,” she said. “When I worked with teachers who tried it, their students did succeed. And the teachers told me that for the first time in their careers, they heard students give positive feedback about learning proof.”

The key, Cirillo said, is breaking down the process of developing a mathematical proof into smaller components, easing students into the idea that a formal proof is necessary as a way for them to explain their thinking. She developed a series of specific sub-goals for students to master as they learn the overall skill.

“One of the goals is for students to understand proof as a mathematical process,” she said. “Instead of following a teacher’s demonstration of proving and then copying that process — a kind of show-and-tell method that’s often used now — students can learn proof as a way to reason.”

Cirillo will work closely with classroom teachers over the next five years. Her first steps will include recruiting teachers in the area and developing a series of 16 lesson plans and student assessment materials.

In the second year of the research, she will have teachers from the exploratory study pilot the new lesson plans, and she will collect baseline data on a new group of teachers. That summer, teachers will use the new approach to teach small groups of students. During the next two school years, teachers will use the lesson plans in their classrooms.

Throughout the process, Cirillo said, lessons will be video-recorded, and teachers will be valuable partners in assessing how the lessons work and what should be changed to fine-tune them. Eventually, the lessons may be compiled into a professional development program.

“My research model is a professional development model, where I consider the teachers to be my partners and colleagues as we work to solve a problem of practice,” Cirillo said. “Connecting research to practice — that’s always my goal.”

Article by Ann Manser

Photo by Ambre Alexander Payne