ISS project

UD researcher prepares studies for International Space Station

1:31 p.m., Sept. 5, 2013--A University of Delaware researcher has received NASA funding to prepare experiments for the International Space Station (ISS).

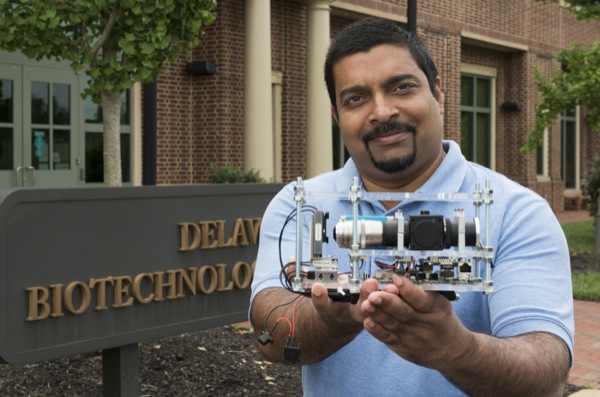

Chandran Sabanayagam, an associate scientist at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute (DBI), is developing a multi-generational study using the small microscopic worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, to understand how gravity affects biological processes at the cellular and molecular scales.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

“Little is known about the influence of gravity on living systems, and how organisms can adapt over many generations to changes in gravity,” Sabanayagam said. “We want to understand the influence gravity has on gene expression, through epigenetics.”

Epigenetics is the study of inheritable changes in protein expression, due to chemical modifications of DNA histone proteins. Unlike DNA mutations that are typically thought to drive evolution in a slow process that can take hundreds to thousands of years, epigenetic changes can occur over a single generation to help an organism adapt to sudden changes in the environment.

Before the project takes flight, Sabanayagam will be preparing ground-based studies that will focus on creating an "altered gravity" environment for the worms.

Sabanayagam’s epigenetic studies will require screening a number worm strains to find the ideal specimen for space investigations. The current cost for ISS crew members to handle experiments is $50,000 per hour, making screening in space cost prohibitive.

Therefore, Sabanayagam needs to develop an altered gravity environment here on the ground. This will be achieved through the development of a rotating fluorescence microscope. Altered gravity will be produced by rotating the microscope and worms in such a manner that the worms become periodically inverted, he said. “If we rotate the microscope and worms in a specific manner, the worms will free-fall and perceive a microgravity environment similar to the ISS.”

This, he said, is one scheme for producing altered gravity whereby the gravity vector moves continuously and smoothly in one direction. But Sabanayagam will also be able to produce other exotic altered gravity environments that probably do not occur in nature, such as random and abrupt changes in rotation.

“The key strategy is to identify genes that respond to altered gravity, and we hypothesize that these genes, or a subset of them, will also be influenced by microgravity,” he said.

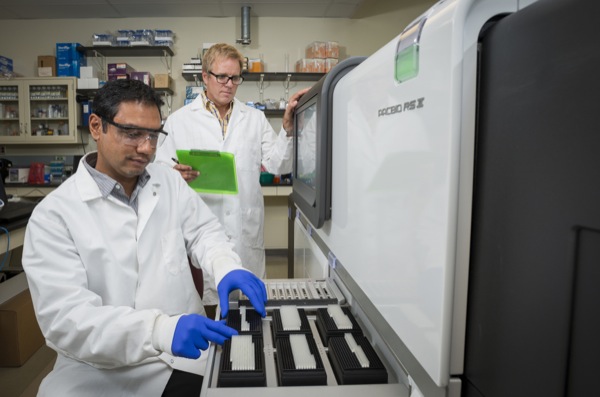

Sabanayagam, who received the grant in part due to his ability to access leading-edge equipment at UD, said the study will utilize the third generation Pacific Bioscience RS DNA sequencer at DBI’s DNA Sequencing and Genotyping Center. UD is one of the few universities in the country equipped with the advanced device.

“The Pacific Biosciences RS DNA Sequencer is the most advanced DNA sequencing platform currently available, UD is extremely fortunate to have it,” said Bruce Kingham, director of the DNA Sequencing and Genotyping Center and project collaborator. “The Pacific Biosciences platform affords us a new level of resolution and specificity that has never existed in genomics research.”

“Once we identify genes that are up-regulated or down-regulated as a result of the animals’ exposure to altered gravity, we can label those genes with fluorescent biomarkers,” Sabanayagam said. “Then we can follow the expression of those genes throughout many generations exposed to altered gravity, ultimately onboard the ISS.

“Worms and humans are more closely related than you would think, because nature seems to conserve basic functions across many diverse animals. The fundamental mechanisms of gravity adaptation in worms will likely resemble a similar response in humans.”

This is not Sabanayagam’s first time developing a microscope whose ultimate destination is space. In fact, the design of the altered gravity microscope builds on a prototype developed for an earlier NASA-funded project where Sabanayagam is working on building a small high resolution microscope that will be used for experiments in satellite orbit.

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson