Redding Lecture

Law professor, activist Lani Guinier urges new look at access to higher education

8:45 p.m., Oct. 3, 2013--If the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court was the beginning of the end of the Jim Crow system of repression against African Americans, then activist, author and educator Lani Guinier wants Americans to think about who really won and who lost.

Guinier, Bennett Boskey Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, spoke to issues of societal privilege and access to higher education during the annual Louis L. Redding Lecture, held Wednesday, Oct. 2, in Gore Recital Hall of the Roselle Center for the Arts.

People Stories

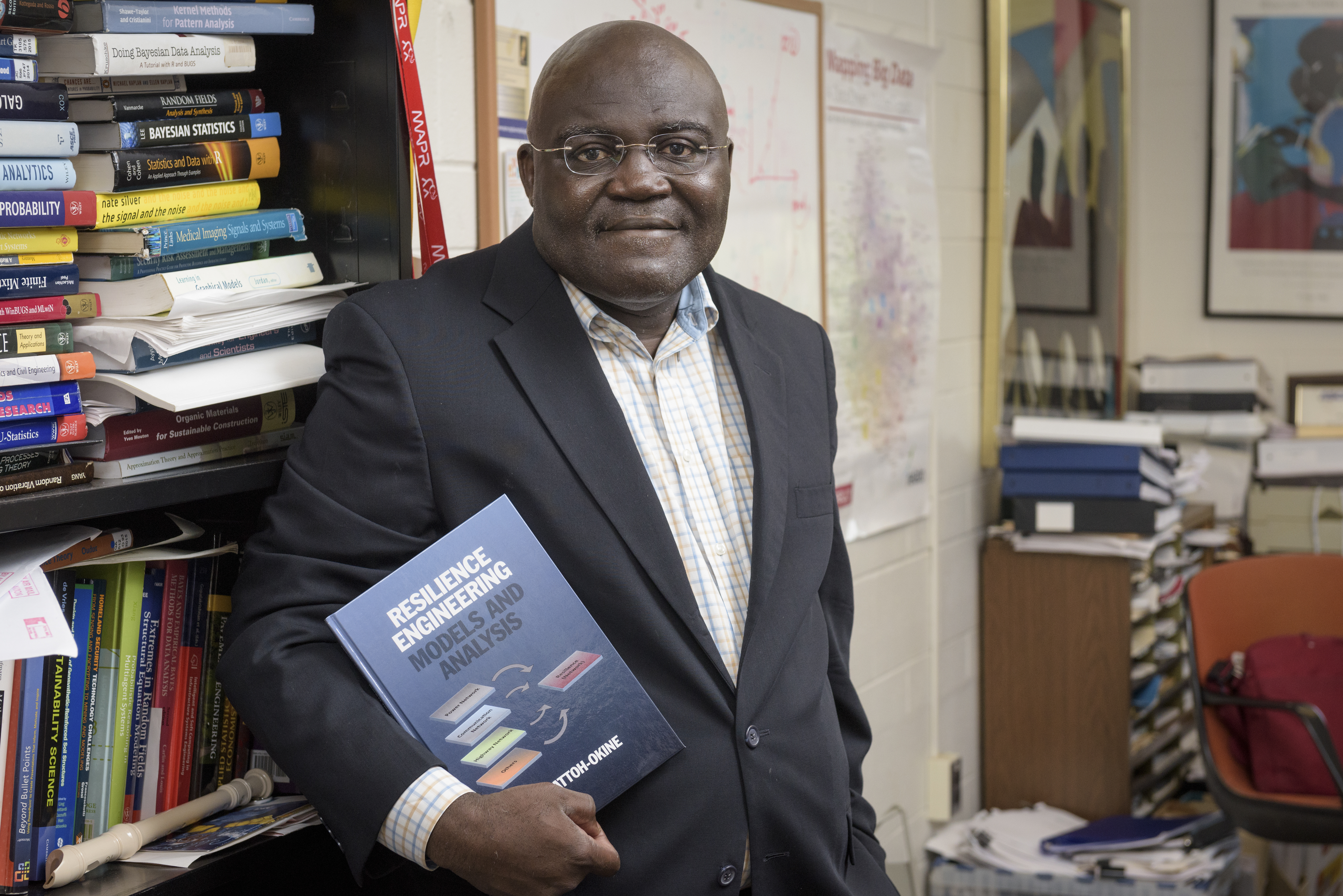

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

The annual lecture recognizes the civil rights efforts of Louis L. Redding, the first African American attorney admitted to the Delaware Bar in 1929. A new residence hall on UD’s East Campus has been named in his honor.

After welcoming remarks by University Provost Domenico Grasso, Guinier was introduced to the standing-room-only audience by Margaret Andersen, Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Professor of Sociology and executive director of the President's Diversity Initiative. Andersen also welcomed members of the Redding family in the audience.

“Lani Guinier is an accomplished social justice advocate and in 1998 was the first African American woman appointed to a tenured professorship at Harvard University,” Andersen said. “Because of her stalwart commitment to social justice, she is seen as a woman who doesn’t shrink from public controversy.”

In beginning her talk, “Rethinking Race and Class,” Guinier lauded the efforts of the Delaware attorney who was instrumental in ending segregation in education at the state and national level.

“I’m really happy to have the honor and privilege of speaking to you in the name of Louis L. Redding,” Guinier said. “He was a lawyer, and many of the cases that he won became the basis for his participation in the most famous civil rights case and perhaps the most famous case brought before the U.S. Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Education.”

Almost 60 years later, Guinier questioned whether or not the landmark case went far enough to justify the celebrations marking the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s and beyond.

“We have repudiated Jim Crow, but not in terms of the institutional hierarchy,” Guinier said. “Some groups have been able to succeed, but others have not been so successful in a society that allocates privilege to a very small percentage of people.”

In examining the plight of those who feel excluded from a societal hierarchy based on power and privilege, Guinier noted confusion and bitterness experienced by working class and poor white students after the 1957 desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas.

“When the nine African American students showed up to go to classes, they were met by a mob of white people who were very angry,” Guinier said. “At the same time, the upper middle class citizens of Little Rock had just put up a new high school on the west side of the city, a school for which they had privately raised the money to build.”

Left behind at the old high school, the working class and poor white students felt a sense of lost opportunity, being denied access to an American dream where the means to success were hard work and playing by the rules, Guinier said.

“The nine children at Little Rock Central High School were very brave,” Guinier said. “At the same time, we also underrated the confusion of the poor whites who saw the upper class whites move to the new school on the other side of the city.”

The experiences of such groups, Guinier said, mirrors the miner’s canaries that were taken into the mines because their fragile respiratory systems would signal the dangerous presence of toxic air and the need for the men to evacuate immediately.

Guinier detailed this societal metaphor in The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power, Transforming Democracy, a book she coauthored with Gerald Torres.

A selective distribution of resources in American society, Guinier said, reveals that the issue is not just about race, but also about class.

“We also have not provided for working class white people, and as a result racism becomes a useful tool for redirecting resources,” she said. “This creates interference and hostility between people who really have a lot in common.”

When it comes to access to higher education and the top undergraduate and graduate programs, Guinier said that standardized tests and a culture of competition serve to keep women and underrepresented students for realizing their full academic potential.

“In the case of law school, women are the miner’s canaries,” Guinier said. “All of this is not about race or class or gender, but the way in which we take for granted that competition is the basis for awarding individual merit.”

In noting that America has a lot to be proud of, Guinier urged her audience to pay attention and learn from its “miner’s canaries” who see things from a very different perspective.

“We need to take a look at this,” Guinier said. ”We can do a lot better.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Lane McLaughlin