Taming hurricanes

Offshore wind turbines could weaken hurricanes, reduce storm surge

7:45 a.m., Feb. 26, 2014--Wind turbines placed in the ocean to generate electricity may have another major benefit: weakening hurricanes before the storms make landfall.

New research by the University of Delaware and Stanford University shows that an army of offshore wind turbines could reduce hurricanes’ wind speeds, wave heights and flood-causing storm surge.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

The findings, published online this week in Nature Climate Change, demonstrate for the first time that wind turbines can buffer damage to coastal cities during hurricanes.

“The little turbines can fight back the beast,” said study co-author Cristina Archer, associate professor in the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment.

Archer and Stanford’s Mark Jacobson previously calculated the global potential for wind power, taking into account that as turbines are generating electricity, they are also siphoning off some energy from the atmosphere. They found that there is more than enough wind to support worldwide energy demands with a negligible effect on the overall climate.

In the new study, the researchers took a closer look at how the turbines’ wind extraction might affect hurricanes. Unlike normal weather patterns that make up global climate over the long term, hurricanes are unusual, isolated events that behave very differently. Thus, the authors hypothesized that a hurricane might be more affected by wind turbines than are normal winds.

“Hurricanes are a different animal,” Archer said.

Using their sophisticated climate-weather model, the researchers simulated hurricanes Katrina, Isaac and Sandy to examine what would happen if large wind farms, with tens of thousands of turbines, had been in the storms’ paths.

They found that, as the hurricane approached, the wind farm would remove energy from the storm’s edge and slow down the fast-moving winds. The lower wind speeds at the hurricane’s perimeter would gradually trickle inwards toward the eye of the storm.

“There is a feedback into the hurricane that is really fascinating to examine,” said Archer, an expert in both meteorology and engineering.

The highest reductions in wind speed were by up to 87 miles per hour (mph) for Hurricane Sandy and 92 mph for Hurricane Katrina.

According to the computer model, the reduced winds would in turn lower the height of ocean waves, reducing the winds that push water toward the coast as storm surge. The wind farm decreased storm surge — a key cause of hurricane flooding — by up to 34 percent for Hurricane Sandy and 79 percent for Hurricane Katrina.

While the wind farms would not completely dissipate a hurricane, the milder winds would also prevent the turbines from being damaged. Turbines are designed to keep spinning up to a certain wind speed, above which the blades lock and feather into a protective position. The study showed that wind farms would slow wind speeds so that they would not reach that threshold.

The study suggests that offshore wind farms would serve two important purposes: prevent significant damage to cities during hurricanes and produce clean energy year-round in normal conditions as well as hurricane-like conditions. This makes offshore wind farms an alterative protective measure to seawalls, which only serve one purpose and do not generate energy.

Jacobson and study co-author Willett Kempton, professor in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, weighed the costs and benefits of offshore wind farms as storm protection.

The net cost of offshore wind farms was found to be less than the net cost of generating electricity with fossil fuels. The calculations take into account savings from avoiding costs related to health issues, climate change and hurricane damage, and assume a mature offshore wind industry. In initial costs, it would be less expensive to build seawalls, but those would not reduce wind damage, would not produce electricity and would not avoid those other costs — thus the net cost of offshore wind would be less.

The study used very large wind farms, with tens of thousands of turbines, much larger than commercial wind farms today. However, sensitivity tests suggested benefits even for smaller numbers of turbines.

“This is a paradigm shift,” Kempton said. “We always think about hurricanes and wind turbines as incompatible. But we find that in large arrays, wind turbines have some ability to protect both themselves and coastal communities, from the strongest winds.”

“This is a totally different way to think about the interaction of the atmosphere and wind turbines,” Archer said. “We could actually take advantage of these interactions to protect coastal communities.”

The paper, titled “Taming Hurricanes with Arrays of Offshore Wind Turbines,” appears online on Feb. 26 in Nature Climate Change and will be published in print in March.

Article by Teresa Messmore

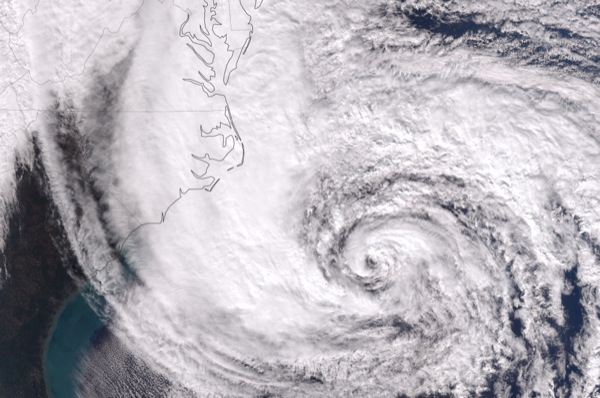

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Suomi NPP VIIRS data provided by Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS)

Photo by Ambre Alexander Payne