Beauty and horror

Environmental author Terry Tempest Williams finds beauty in the midst of devastation

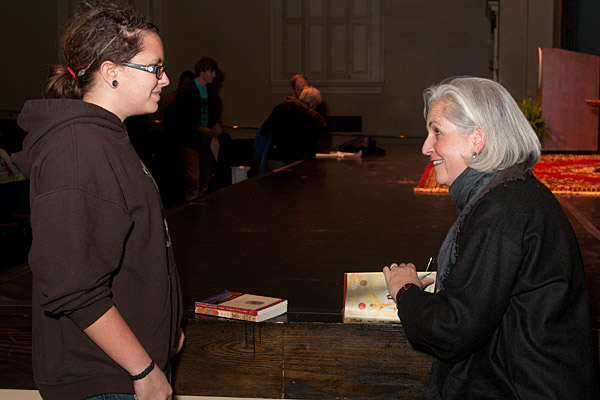

5:31 p.m., March 6, 2012--From the devastation of disasters such as last year’s Japanese earthquake and tsunami or accidents such as the Gulf oil spill or human brutality such as the Rwandan genocide, beauty can emerge, environmental author and activist Terry Tempest Williams told an audience of about 250 at Mitchell Hall last week.

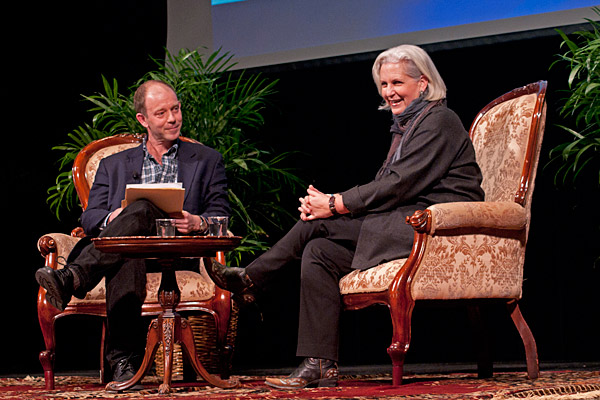

Williams spoke on campus as part of the DENIN Dialogue Lecture Series, hosted by the Delaware Environmental Institute. She was interviewed on stage by McKay Jenkins, Cornelius Tilghman Professor of English and co-director of the College of Arts and Sciences’ Environmental Humanities Initiative.

Campus Stories

From graduates, faculty

Doctoral hooding

Williams is the author of the environmental classic Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place and a dozen other books that touch on themes of environmental destruction and preservation and the power of community and storytelling to overcome the barriers to constructive dialogue about environmental issues.

In her most recent book, Finding Beauty in a Broken World, Williams uses the art form of mosaic as a metaphor to describe how broken ecosystems and human communities may be pieced back together into something of beauty after destructive episodes.

In her conversation with Jenkins, Williams, a native of Utah, described her awakening as a young girl to the possibility of merging her passions for language and landscape through the writing of Rachel Carson in Silent Spring, which her grandmother shared with her.

“I was raised to see the land as whole -- even as holy,” she said.

At the same time, her family’s business for four generations has been laying pipe to carry water and sewage, oil and natural gas, and fiber optic cable across eight western states. The tension between their love of the land and the livelihood earned from it has long been part of her family’s dinner table conversations.

It was the realization after her mother’s death from cancer when Williams was 34 that the large number of cancer deaths in her family were likely the result of exposure to fallout from above-ground nuclear testing in the 1950s that moved her to take a more active stance in her writing and in her behavior. Her first act of civil disobedience was to cross the line at the federal nuclear testing facility in Nevada and face arrest. Since that time, Williams has been motivated to bear witness to environmental devastation and its human toll through her writing.

“I would say that whatever I have been able to bear witness to in my life has been out of love and out of loss,” she said. “It started for me as a young girl when I contemplated life without birds, which were everything to me. I have always been very aware of the fragility of life.”

Williams, who is the Annie Clark Tanner Scholar of Environmental Humanities at the University of Utah, has turned to storytelling as one of the most effective ways of bearing witness. She said she tries to avoid writing polemics and just lets the stories of people and places speak for themselves.

She related to the audience how a storytelling and writing workshop that she and a class of graduate students held for citizens in an area of Wyoming affected by natural gas extraction was interrupted by a powerful state senator who loudly condemned what they were doing as “propagandizing.”

Instead of reacting to the senator’s vitriol on equal terms, she and the students calmly invited him to become part of their storytelling circle, and in the act of telling his own story, the angry senator joined the community.

“In the act of storytelling, we do bypass rhetoric and pierce the heart,” she said, “and we speak from a place of honesty and receive in a spirit of empathy and compassion.”

Jenkins posed the question of how she was able to deal with the grief of all that she had heard and witnessed over time in her own family, in the degradation of the environment and in places like Rwanda where Williams had traveled to help build a mosaic memorial to the victims of genocide.

“I have a friend who said once, ‘Terry, you are married to sorrow,’ and I said ‘No, I just choose not to avert my gaze,’” Williams replied. “I’m not sure we can ever learn to love death, but death is a part of life, and I respect it and it is a great teacher.”

Williams described how she felt compelled to visit the U.S. Gulf Coast to witness firsthand the devastation of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. She recalled a boat trip with an experienced pilot and advocate to a site where the oil slick extended as far as the eye could see in every direction, at a time when the press had declared that the spill was 80 percent contained.

“Our eyes were burning and it was horrible,” she said. “I asked the pilot what was the worst thing he had seen, and he said that the most moving thing he saw was when they had set fire to the ocean and were burning the surface oil to get rid of it, he had seen a line, a pod of dolphins, side by side by side, on the edge of the oil, watching.”

But, she added, it wasn’t until she left the area of devastation and saw the beauty in more pristine areas of the Gulf that she had begun to cry.

“It was the beauty that really broke us open,” she said. “I think when we bear witness, it’s not a passive act. It’s an act of conscience and consciousness that I think does have consequence. I guess it’s a way of saying that unless we grieve what we’re losing, unless we honor the beauty, then we don’t find our way through to that place of action.”

The dialogue with Terry Tempest Williams was co-sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences, the CAS Environmental Humanities Initiative, the Department of English and the Honors Program.

The event was partially funded by a grant from the Delaware Humanities Forum, a state program of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Article by Beth Chajes

Photos by Duane Perry