After the Crime

Professor's book examines the power of victim-offender dialogue programs

1:12 p.m., June 27, 2011--In her late 50s, Donna was a woman who had spent her life trusting others. She took in foster children, waved to strangers from her yard, and on a chilly October night in 1996, opened the door for a young boy on her patio.

The 17-year-old outside had only planned to rob her. Instead, he assaulted and raped the tiny, silver-haired lady who had been lying half-asleep in her recliner, waiting for her husband to come home.

People Stories

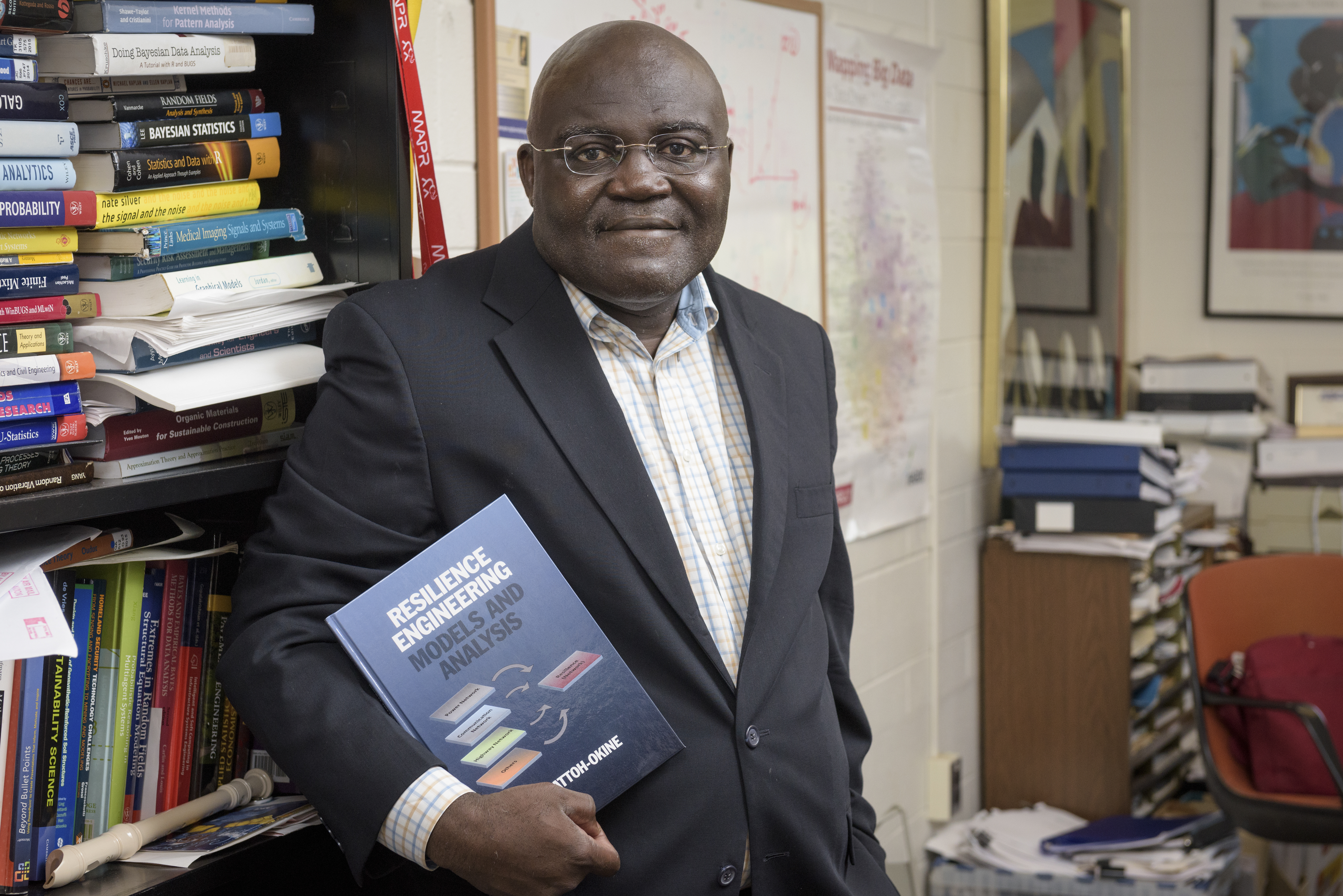

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

The offender was soon apprehended, but questions haunted Donna for years.

Had he been stalking me? Did I fight back? Why me? What did I do?

Seven years later, she saw a public service announcement for Victims' Voices Heard, a non-profit organization in Delaware that offers survivors of violent crimes the opportunity to meet their incarcerated offenders face-to-face. It was through the program that she sat across from her attacker and found her answers.

No, he hadn’t been stalking her. Her house was simply the first one he saw, and yes, she fought back.

“I’m not proud of what happened to me, but I’m proud of the recovery of me,” Donna says in After the Crime, a new book written by University of Delaware Professor Susan Miller that examines the power of “restorative justice” dialogues between victims and offenders.

While the traditional criminal justice model considers crime a violation of the law committed against the state, Miller, a professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, explains that the restorative justice model views crime as a violation of people and relationships. It therefore focuses on meeting victims’ needs and facilitating offender responsibility to repair the harm.

Delaware is one of only 25 states with restorative justice dialogue programs for violent crimes, and Miller, an internationally renowned feminist scholar on gender and policy issues, posits such programs are especially powerful in cases of gender violence.

“There has been real reluctance to use restorative justice in cases of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, child sexual abuse and the like,” she says. “We should reconsider that, at least with post-conviction strategies that occur often years after the incidents.”

Philosophically, Miller understands the rationale: these crimes are characterized by power, control and manipulation. Her book, however, shows how restorative justice dialogues can create “a power shift for victims.”

After the Crime examines 10 different cases from the Victims’ Voices Heard program, including rape, domestic violence, murder, incest and DUIs. All but two (a DUI and murder) involved violent crimes against women and were resolved with empowered victims confronting their attackers and, in some instances, forgiving them.

The effects were similarly powerful for the offenders, and Miller sees that as a larger societal gain.

“Nearly 97 percent of prisoners are released back into our communities,” she says. “If we’ve done nothing to look at their lives, at issues with anger management, victim empathy, conflict resolution and communication, then we’re releasing people who are almost doomed to fail.”

Jamel, who attacked Donna 15 years ago, participated in the Victims’ Voices Heard program because he wanted to apologize and “ease [her] of any agony she may be feeling,” he told Miller. “Whatever needed to be done, I wanted to do it.”

In addition to meeting, he wrote apology letters to Donna and her family members, expressing “how I hurt her, things I wanted to do to make it right, how I put my life together, what I hoped to accomplish during the meditation process.”

To his surprise, Donna wrote back.

“I don’t hate you, and the anger has long passed, ” she wrote.

Donna credits Victims’ Voices Heard, founded in 2002 by Kim Book, a mother whose only daughter was murdered by a school acquaintance, with a newfound peace.

“I think that if I had met Kim years before, I could’ve saved myself a lot of years of needless— I don’t want to say suffering because I didn’t even know I was suffering,” she tells Miller in After the Crime. “I didn’t know what I was doing to myself 'til I stopped doing it.”

“Now,” she adds, “I have my curtains open and the sun shines in and I sit out on the porch and I talk to my neighbors.”

Article by Artika Rangan

Video by Andrea Boyle