- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

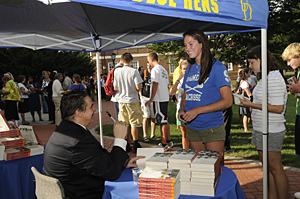

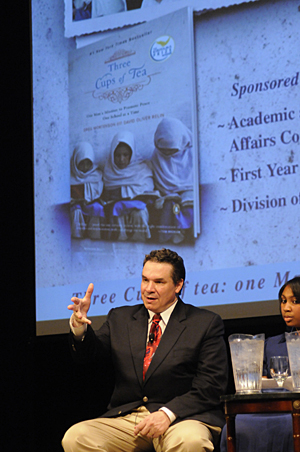

12:54 p.m., Sept. 4, 2009----When Greg Mortenson, author of the best-selling book Three Cups of Tea, wandered into the village of Korphe in Pakistan in 1993, at the end of a failed attempt to reach the summit of K2, the world's second highest mountain, he had no idea how much his future would be intertwined with the villagers who offered him rest and shelter.

Mortenson, the co-founder of the Central Asia Institute, described his transformational experience during two talks to about 1,500 freshmen students and members of the UD community on Thursday, Sept. 3, in Mitchell Hall.

The two seminars filled the 650-seat Mitchell Hall and about 200 listened to the talk in overflow rooms in the adjacent Gore Hall.

Three Cups of Tea, which has sold more 3 million copies, was co-authored with David Oliver Relin.

Featured in the book is the compelling personal account of how Mortenson has worked to make a difference by building schools in the most remote regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“To honor the memory of my sister Christa, who died in 1992 from a massive seizure after a lifelong struggle with epilepsy, I decided to climb Pakistan's K2, the world's second highest mountain in the Karokoram range,” Mortenson said. “After not quite reaching the top, I got lost and ended up in Korphe, where I was welcomed by the chief elder Haji Ali.”

Recovering from his 84-day ordeal on the mountain, Mortenson came across a group of children in the village who were sitting in the dirt and writing with sticks in the sand.

“They had no teacher because the village could not afford the cost of paying someone to do this,” Mortenson said. “I made a promise to Haji Ali that I would come back and build them a school.”

It would be nearly three years before this goal was realized, during which time Mortenson said that he had a pretty steep learning curve when it came to fund raising and school building.

“When I came back, I was told we had to build a bridge before we could build the school,” Mortenson said. “Three years later we had not gotten very far. I was micro-managing everything. Haji Ali told me I needed to go sit down and let the villagers build the school. Six weeks later the school was built.”

As of 2009, Mortenson has established more than 90 schools providing education to more than 34,000 children, including 24,000 girls, in the rural and often volatile regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan where few educational opportunities existed before.

“There are 120 million children in the world who can't go to school, and 78 million of these children are female,” Mortenson said. “I think that the top global priority is that every single child in the world should be able to go to school.”

Mortenson noted that the Taliban has bombed or destroyed more than 800 schools in Afghanistan and 650 schools in Pakistan, with nearly 90 percent of them being schools for girls.

“Their greatest fear is that a girl will get an education, because they know if they do, they will be able to control their society,” Mortenson said. “Some of our teachers are former Taliban members who got out because their mothers told them what they were doing was not a good thing.”

When women in Afghanistan and Pakistan are asked if they want to see more troops, their answer is, “We want peace. We want no fear that our children will die. We want our children to go to school,” Mortenson said.

While there is much to be despondent about in Afghanistan, Mortenson said that the American military commanders have begun to acknowledge that they need to listen more to the people in those areas and to build better relationships.

“Afghanistan is a warrior culture, and the elders respect the opportunity to meet our senior American military leaders,” Mortenson said. “Politicians can start and stop wars, but it is education that brings peace.”

Mortenson said he is encouraged by the growing number of young people in schools such as UD that have committed to helping others at home and around the world.

“I read an article in U.S. News & World Report that in 1970, nearly one-third of college students were participating in service-related work. By 1990, one generation later, this had fallen to 18 percent. Today, it is up to 40 to 45 percent,” Mortenson said. “While colleges can take some of the credit, the main reason it is happening is that it is student driven.”

Mortenson also answered questions from a panel that included Ralph Begleiter, UD's Edward and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Professor of Communication and Distinguished Journalist in Residence.

Joining Begleiter at the 3:30 p.m. seminar were Taria Pritchett, a sophomore education major from Wilmington, and Gabriel Mendez, a sophomore political science and human services major from Monroe, N.Y. Student panelists at the 7:30 p.m. session included Danna Principati, a senior Honors Program elementary teacher education major from West Chester, Pa., and Aaron Yamamota, a senior Honors math education major from Glenolden, Pa.

The questions read by the student panelists were selected from among more than 100 submitted by members of the freshman class who read Mortenson's book as part of the First Year Experience Program requirement. The program is designed to help students succeed both academically and socially in their first year at UD.

When asked how the schools worked to create a curriculum in the Afghan schools dictated by Islamic law, Mortenson answered, “We had elders come in and we had Islamic education, which included teaching five languages, including Arabic.”

About finding the energy to accomplish the work of the Central Asia Institute in building schools and education students, Mortenson said,”You have to be a little crazy and be passionate about what you are doing. You have to not be afraid to think outside of the box.”

The occasional failure or setback in any kind of service work is something to be expected as individuals and groups pursue their goals of helping others. “It takes a lot of hard work and perseverance. There is no way around this,” Mortenson said. “You also must not be afraid to fail. Where we really fail is when we don't listen to other people.”

The thing that stands out the most among all his experiences, Mortenson said, is being there to see a child write his or her own name for the first time. “That is a very incredible experience, because it means that now that child has an identity,” he said. “It also is very precious when your own children learn to read and read their story books to you.”

Mortenson said that he also learned an important lesson from Haji Ali, who died after seeing the village school become a reality thanks to the efforts of Mortenson and the Central Asia Institute and Pennies for Peace projects.

“I saw him once meditating and he told me that someday he would die, and when that happened, he wanted me to visit his grave and listen to the wind,” Mortenson said. “After he died, I did what he asked. I wondered just what I would hear, and then it came to me. It was the voices of the children reading in their school.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Duane Perry