By tracey bryantOffice of Communications & Marketing

Human migration has lots of consequences for society, including national security

Mark Miller says he was thought of as "an oddball" for choosing human migration as the focus of his studies when he was an undergraduate and later on in graduate school.

"Today, thirty to forty years later, people see a logic to my madness," Miller says softly.

Miller, the Emma Smith Morris Professor of Political Science and International Relations at UD, is a leading expert on international population movements and their consequences across society, from economic development to national security.

Governmental organizations and the United Nations have sought Miller's expertise, and he has testified before Congress and various U.S. commissions on immigration questions. He also has helped lead six Fulbright Institutes on U.S. national security and foreign policy and currently directs the National Security Institute at UD. The latter program, sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, seeks to connect its participating policy specialists and scholars from around the world in an "epistemic community," a network of knowledge-based experts who have been taught together and will maintain lasting ties.

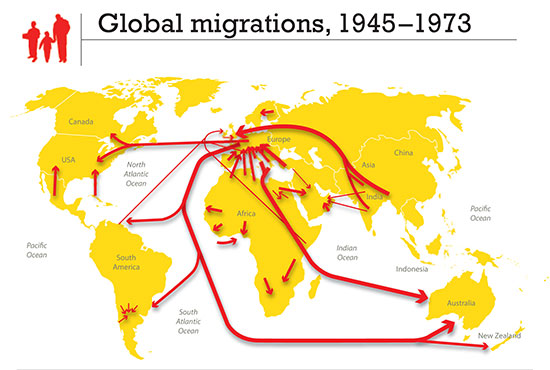

International migration is nothing new, Miller says, but understanding where people are moving now and why can help policymakers better navigate the more globally integrated world ahead.

Throughout history, groups of people have left their homeland to look for new opportunities or to escape conflict. And many millions too were enslaved and forcibly transported. Indeed, Africans long outnumbered Europeans arriving in the New World, Miller notes.

Miller's Irish farmer ancestors, besieged by the Irish Potato Famine, sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States to seek a better life. They were part of one of the largest mass migrations of people in history — between 1820 to 1920, some 60 million Europeans emigrated to the New World, principally to the United States.

Since 1970, Miller says, the world has been experiencing a new age of migration, and not just on a transatlantic scale. Growing socioeconomic gaps in Latin America have propelled people to the United States and southern Europe. Asians and Africans began migrating, with significant numbers of Black Africans moving to France and elsewhere in Europe. Eastern Europeans poured into western Europe, particularly Poles into Ireland and the United Kingdom. And countries along the Persian Gulf began hiring migrant workers — first from other Arab countries and then from Asia.

In addition to these phenomena, in 1990, the Cold War ended with the implosion of the Soviet Union, which marked the need for a new national security policy in the United States.

But developing such a policy was much more complex now, crossing over into the domestic and foreign policy realms. The rise of the Internet and new communications technologies, ethnic cleansing and other violent conflicts, the increasing role of women as migrant laborers and as victims in human trafficking, and concerns about climate change and displaced peoples became new factors in the flowof people and in the flow of policy.

And then came 9/11.

"Al-Qaeda was under the radar screen because of the way our country's security experts were trained," Miller notes.

Although the intertwining subjects of international migration and terrorism came to the fore after 9/11, as Al-Qaeda sleeper cells were identified far beyond the Middle East — in England, Germany and elsewhere — Miller had been studying the dual subjects since he was an undergraduate and says he has always seen them as "one piece of cloth."

"Although radical groups like Al-Qaeda constitute a tiny fraction of the Muslim population," Miller says, "a long time ago, in studying the evidence, I argued that international migration from the Middle East to Europe had important security implications for the United States."

Since the launch of the U.S. War on Terrorism–invasion of Iraq in 2003, thousands of radical Muslims have received military training in camps in the Middle East and North Africa and some have subsequently returned to Europe.

Miller also sees these threats to U.S. national security in the future:

Miller is optimistic, however, that Muslim immigrants can continue to incorporate into Western democracies.

"Muslims in the United States are different — they came here for different reasons. They were not recruited as foreign workers, as was the case for so many in Europe," he says.

"The gist of American immigration history is that groups viewed as problematic and a security threat at one juncture in time will go through an incorporation process if we give them a chance.

"The classic case was the Irish," Miller notes. "I think that will be the outcome for Muslims, as well as for Mexicans and for Guatemalans in the U.S. The historical evidence is on my side."

Miller's book The Age of Migration (www.age-of-migration.com), co-authored with Stephen Castles and published by Guilford Press, is regarded as a classic by policymakers, scholars and journalists. It is a recommended text in political and social science courses around the globe. The fifth edition is slated for publication in 2012.

Additionally, Miller is the author or co-author of The War on Terror in Comparative Perspective; Foreign Workers in Western Europe: An Emerging Political Force; The Unavoidable Issue: United States Immigration Policy in the 1980s; and Administering Foreign Worker Programs: Lessons from Europe.

Miller also has written more than 100 articles, chapters and monographs on immigration, including two com-missioned monographs for the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform. Learn more on Miller's web site.