By tracey bryantOffice of Communications & Marketing

What do ants and slime mold (cool!) have in common? They're inspiring new wireless communications networks being developed by UD scientists. . . .

Lou Rossi is a mathematician, not a biologist, but he can wow you with his knowledge of ants.

Did you know that there are over 10,000 species of ants?

Or that these little insects add up to 15–20 percent of the total terrestrial biomass — all the living stuff — on Earth?

"Although ants are nearly blind, they are very successful at finding food," says Rossi, who is an associate professor in UD's Department of Mathematical Sciences. "You miss a few crumbs on the countertop, and you find ants there the next morning. How do they do that? Ants are computing machines," he says. "They do spatial computing, leaving chemical markers — pheromones — on the ground to communicate information to other ants."

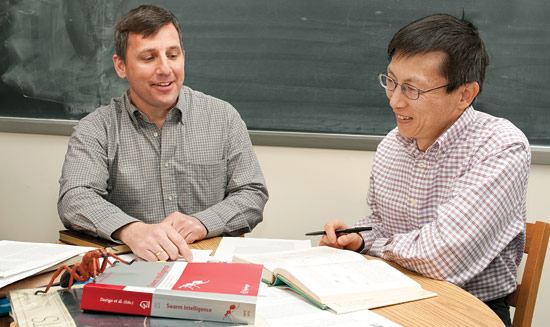

Taking their inspiration from the social behavior of ants, Rossi and Chien-Chung Shen, associate professor in the Department of Computer and Information Sciences, are developing the complex mathematical algorithms required to operate a secure, wireless communications network for soldiers in the battlefield.

The initial research was funded by the National Science Foundation. The current effort is supported by a U.S. Army Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant and involves an industry collaborator, Scalable Network Technologies Inc., based in Los Angeles.

The mobile ad hoc network (MANET) that Shen and Rossi are developing is very different from cell phone networks that rely on cell towers as base stations for message transmission and reception. Such towers would be easy targets in the battlefield. But setting up a MANET has its own set of complicated challenges.

"Every node, or device, in a mobile ad hoc network has to relay messages to other nodes, and most messages will be relayed over multiple hops," Shen says. "If you think of a group of soldiers in a battlefield, not all of them are in range, so they have to rely on other soldiers to route messages to them. Every node has to be a router, and all the nodes are moving. You know who you want to send a message to, but you don't know where they are."

Using ant behavior as their model, Shen and Rossi are developing the networking architecture and networking protocols, or "language," that will enable communication between the MANET nodes.

"Ants efficiently self-organize a large number of unreliable and dynamically changing components for various functions, adapting to the failure of individual ants, to changing conditions and to the lack of explicit central coordination, which makes them an ideal model," Rossi says.

"To solve problems that are inherently complex, we need to look at a system that adapts to uncertainty," Shen points out. "Biological systems designed over billions of years are optimized, so presumably they are more adaptive. That's a driving motivation of our work."

The researchers are generating mathematical algorithms for sending packets of data, passing messages to other nodes, keeping messages, and incorporating markers to maintain information to be routed to other nodes.

Currently in the second of three phases of their SBIR grant, the researchers will put their networking protocols to the test this summer in real-time video demonstrations.

"Our digital ants are already very good at finding the shortest path between nodes, which real ants do very well," Rossi notes.

Ironically, Rossi and Shen met at a presentation at UD on bio-inspired technologies given by a visiting Princeton researcher several years ago. Now Rossi and Shen's collaboration represents one of a small number of research teams working in this novel field in the United States. For example, Harvard scientists are studying bumblebee behavior.

However, the UD team is just as captivated by slime mold and by schools of fish, as they are by ants.

True slime mold, known scientifically as Physarum plasmodium, is a flat, single-celled, amoeba-like organism that can grow to roughly the size of a hand. In response to the chemical cues from nutrients in its environment, slime mold will assemble a complex network of tubes that serves as a resource distribution network for nutrients. This simple creature generates near-optimal networks, connecting multiple food sources throughout the cell body.

"Often, the tubes of a slime mold will be arranged in a geometry that balances efficiency — keeping the total tube length short — and robustness, having multiple paths in case a tube is severed," Rossi says.

The problems faced by slime molds are similar to those that exist in wireless sensor and actor networks (WSANs), which, for example, guide battlefield robots that detect and mark mines.

And in a new National Science Foundation project, the researchers are working to understand swarming by bees and schooling by fish. How many need to be leaders in order to keep the swarm together? With that answer and the anticipated decrease in the cost of robotics in the decades ahead, Rossi foresees the capability to deploy dozens of underwater robots to quickly find the boundaries of the contaminant plume for a disaster like the BP oil spill.

"It would be the ultimate swim team," Rossi says.