Escape from

Fort Delaware

Student sheds light on Civil War mystery

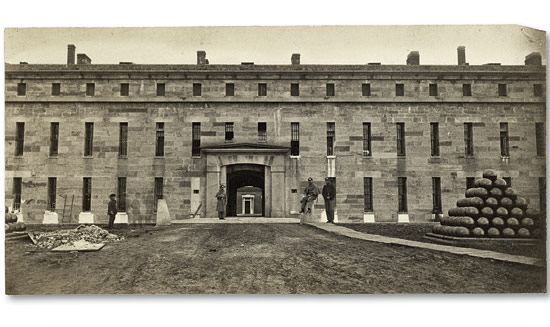

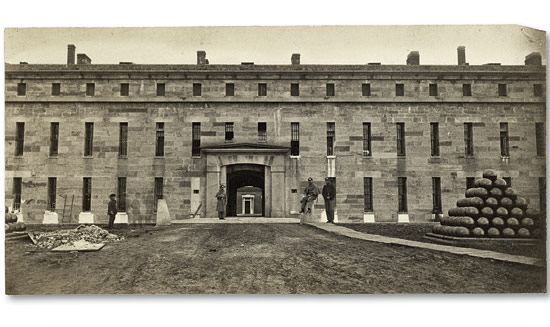

Main entrance ("sally port") to Fort Delaware, post-Civil War, circa 1868 –1870. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of the Delaware Historical Society.

Main entrance ("sally port") to Fort Delaware, post-Civil War, circa 1868 –1870. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of the Delaware Historical Society.

Today, Fort Delaware is a state park. Visitors take a half -mile ferry ride from Delaware City to Pea Patch Island, where costumed interpreters transport visitors back to the summer of 1864. Photograph by Laura M. Lee

Today, Fort Delaware is a state park. Visitors take a half -mile ferry ride from Delaware City to Pea Patch Island, where costumed interpreters transport visitors back to the summer of 1864. Photograph by Laura M. Lee

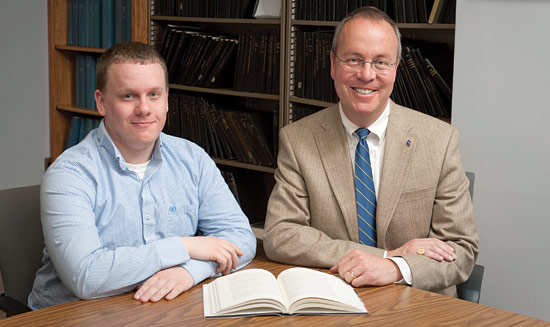

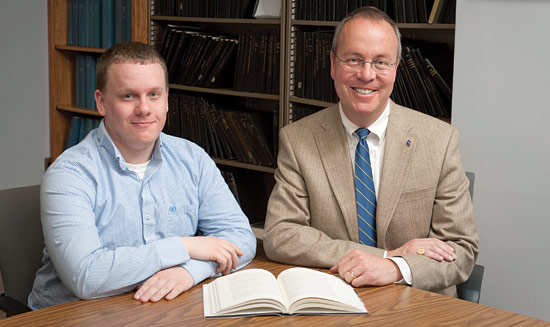

Kevin Mackie (left) with Jonathan Russ, UD associate pro- fessor of history. Russ served as Mackie's undergraduate adviser on the project. Photograph by Kathy F. Atkinson.

Kevin Mackie (left) with Jonathan Russ, UD associate pro- fessor of history. Russ served as Mackie's undergraduate adviser on the project. Photograph by Kathy F. Atkinson.

Pittsburgh heavy Artillery at Fort Delaware, summer of 1864. At one point, there were only 300 Union soldiers to guard nearly 12,000 Confederate prisoners. Lt. henry Warner is the officer (with sword) at left. others are unidentified. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of Delaware State Parks.

Pittsburgh heavy Artillery at Fort Delaware, summer of 1864. At one point, there were only 300 Union soldiers to guard nearly 12,000 Confederate prisoners. Lt. henry Warner is the officer (with sword) at left. others are unidentified. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of Delaware State Parks.

The 153rd military Police Company, Delaware Army National Guard, visited Fort Delaware as part of their annual training in summer 2009. Kevin mackie is in the front row, second from right. he and his brother, Brendan, de- ployed to Iraq in 2007–2008. Photograph by SFC mark P. Del Vecchio.

The 153rd military Police Company, Delaware Army National Guard, visited Fort Delaware as part of their annual training in summer 2009. Kevin mackie is in the front row, second from right. he and his brother, Brendan, de- ployed to Iraq in 2007–2008. Photograph by SFC mark P. Del Vecchio.

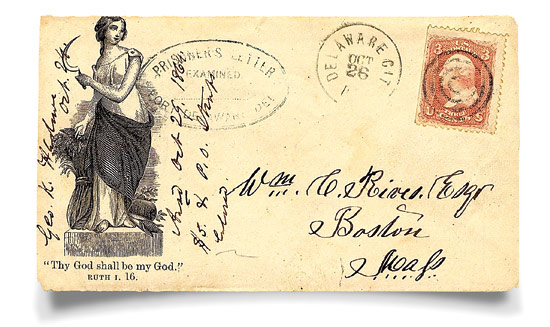

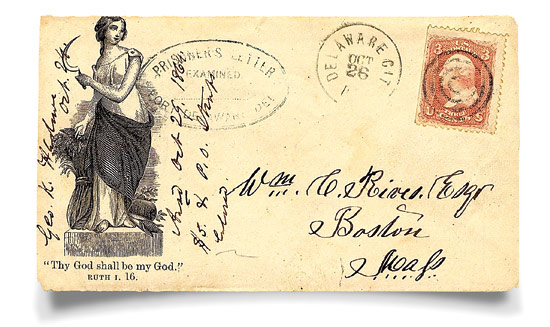

Prisoner letter from Fort Delaware, Oct. 26, 1864

Prisoner letter from Fort Delaware, Oct. 26, 1864

Distant view of Fort Delaware as seen from the river. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Distant view of Fort Delaware as seen from the river. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Prisoners are marched from Fort Delaware in a living history re-enactment of life at the fort. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Prisoners are marched from Fort Delaware in a living history re-enactment of life at the fort. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Fort Delaware's 8-inch Columbiad Cannon is still fired regularly during Heavy Artillery Demonstrations for Fort Delaware visitors. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Fort Delaware's 8-inch Columbiad Cannon is still fired regularly during Heavy Artillery Demonstrations for Fort Delaware visitors. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

In the early days of the Civil War, prison life at Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River was, by most accounts, tolerable. In its first year of operation in 1862, the population varied from 3,434 prisoners in July to only 123 later that year due to routine prisoner exchanges between the North and the South. While the prisoners were mostly Confederate soldiers and officers, some notable political prisoners also were held there.

By August 1863, however, the fort's population had swollen to over 12,000 due to the influx of prisoners from the battles at Vicksburg and Gettysburg.

The brick-and-granite fort, the largest in existence in the United States when completed in 1859, originally was designed as a harbor defense — to keep hostile invaders from sailing upstream to the ports of New Castle, Wilmington and Philadelphia — not to hold prisoners of war.

Wooden barracks sprang up across the island, which was 75 acres at the time, to imprison the growing masses as the Civil War raged on and prisoner exchanges were curtailed.

This sea of humanity, coupled with the stifling heat and humidity of summer and the freezing cold in winter, incubated an epidemic of smallpox and other diseases at Fort Delaware. Lice and bedbugs abounded.

In the end, some 2,400 men — Confederate prisoners, as well as Union guards — would wind up in coffins and be transported across river for burial at Finn's Point cemetery in New Jersey.

Not surprisingly, some prisoners at Fort Delaware would risk their lives in the swift current of the Delaware River in hopes of reaching shore and then venturing south on the "reverse underground railroad."

Reconciling official records with reality

"The official record suggests a low number of prisoner escapes from Fort Delaware. Confederate circles said there were hundreds, maybe thousands. Where is the truth?" asks Jonathan Russ, associate professor of history at the University of Delaware.

Kevin Mackie decided to tackle that question in an undergraduate independent study project last year, with Russ as his adviser. Mackie got the idea for the study from his mother, Laura Lee, interpretive program manager and park historian at Fort Delaware State Park. Lee received her history degree from UD in 1992.

"My mom helped me figure out a topic," Mackie says. "She told me that something she really wanted to find out, and something people always ask about on tours is, how many people escaped from the fort?"

During spring semester 2010, Mackie pored through dozens of official reports, Confederate newspapers and testimonies. He drew on the extensive archives of the Fort Delaware Society. He used JSTOR, a database of journals in the humanities, social sciences and sciences available through the UD Library, to access other primary and secondary sources.

The result of his efforts is "Fort Dela-ware Prisoner Escapes: 1862–1865," a 293-page report containing a fascinating array of historical information. In it, Mackie checks the accuracy of the official records by establishing a list of escaped prisoners and comparing the list to those records.

He provides information sheets on each escaped prisoner, as well as the research he uncovered to back up the escaped claim. Although the official reports by the U.S. military put the total prisoner escapes from Fort Delaware at 54, Mackie's research points to a higher number, between 64 and 103.

Mackie provides a year-by-year account that both paints the scene at the fort and points out questionable statistics relating to prisoner escapes. "Official Reports show that zero prisoners escaped in 1862, which is very clearly not the case," he writes in the report. "According to my research, at least 22 prisoners escaped in 1862, with the majority making their escape in the summer. It is likely that this can be attributed to the brutal hot summers on Pea Patch Island, and better conditions in warmer months for braving the river."

He also documents a number of prisoners who escaped en route to Fort Delaware because of the prison's fearful reputation.

"After 1863, Fort Delaware received the reputation among Confederate soldiers as a horrendous prison, compared by one prisoner to the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta,'" Mackie writes. "The post earned this because after the Battles of Vicksburg and Gettysburg, Fort Delaware's crowding contributed to poor conditions. A smallpox epidemic and the brutal summers and winters broke down a prisoner mentally, physically and emotionally. Whether this reputation was exactly true is not of consequence. It does matter though that the Confederate soldiers perceived this reputation."

The great escapes

"Due to poor recordkeeping during the war, we may never know the real number who escaped, but I believe it is on the higher end of the range Kevin suggests," Russ says.

On the Union side, prison officials were under a lot of pressure, and there was a disincentive to report real numbers. At one point, there were only 300 Union soldiers to guard nearly 12,000 prisoners, Mackie notes. On the Confederate side, there was great propaganda value for the Richmond newspapers to cite more escapes to boost southern morale.

"Still, that's a remarkably small number that escaped," Russ notes. "It confirms how difficult a terrain this was, and many people couldn't swim. Many who were taken as prisoners were exhausted and malnourished, entering the prison in a weakened condition to begin with. If they made it to shore, they were still in hostile territory, and then they had to find people to help them work their way down South."

The methods of escape by prisoners were as varied as the southern states they represented in the great fight.

Some escapees impersonated Union soldiers and snuck out with regiments returning to shore. Others created life preservers out of canteens and floated their way to freedom. One got away on a coal boat; another bribed a guard. The stinking privies and sewers became escape routes.

But most impressive to him, Mackie says, in the prison hospital (one of the best in the military), a prisoner removed a body from a coffin, covered it in blankets and then hid inside, so the story goes. When the coffin reached New Jersey (Fort Delaware's dead were buried across the river at Finn's Point National Cemetery near Fort Mott), the prisoner jumped out and ran into an apple orchard. He later stole a boat and rowed across river to the Delaware shore to begin the next leg on his journey south.

In another instance, a Confederate soldier from Florida is said to have ice skated to freedom. The story from Jackson Wrigley of the 21st Georgia Infantry was retold by his great-great grandson Stan Wrigley, of Lubbock, Texas, in the Fort Delaware Society's "Fort Delaware Notes" in April 1981.

The river had frozen solid in the winter of 1863–64, and some Confederate prisoners from Florida had never seen snow or ice. The Union soldiers were ice skating on the river and asked the Floridians if they would like a try.

"The guards strapped skates on the prisoners and took them out on the river," Wrigley's account goes. "The Floridians of course were falling continuously with the guards laughing uproariously at them. One kept getting farther and farther out on the river although he was having some of the most hilarious pratfalls. But as soon as he was out of musket range of the guards, he set off down the river like a professional skater and was never seen again."

A "remarkable work"

"This is remarkable work for an undergraduate," Russ notes. "Kevin did a great piece of research. For other students, this is a terrific reference tool to better understand not only the conditions of prison life, but to gain insight into recordkeeping in this area and the disincentive to honestly report."

Mackie, a member of the Delaware National Guard, served in Iraq in 2007–2008. Because of the experience, he says the prisoner escapes "hit home" with him.

"I understood the desire to get back into the fight," he says.

Mackie's military service has since paid his way through college. After returning from Iraq, he took classes year-round and graduated from UD with his bachelor's degree in history in January 2011. He is now working at ING Direct in Wilmington, Del.

"I always grew up doing the history thing," Mackie says, noting that he took part in his first Civil War re-enactment at Fort Delaware at the age of eight. "It's where my passion is. My biggest hope is that another historian can take my research, expand it and get an even better number."

Copies of Mackie's report have been provided to the Delaware Historical Society and to the University's Special Collections.

— Editor's Note: Special thanks to Laura Lee and Brendan Mackie for their assistance with the historic photographs included in this article.

Main entrance ("sally port") to Fort Delaware, post-Civil War, circa 1868 –1870. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of the Delaware Historical Society.

Main entrance ("sally port") to Fort Delaware, post-Civil War, circa 1868 –1870. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of the Delaware Historical Society.

Today, Fort Delaware is a state park. Visitors take a half -mile ferry ride from Delaware City to Pea Patch Island, where costumed interpreters transport visitors back to the summer of 1864. Photograph by Laura M. Lee

Today, Fort Delaware is a state park. Visitors take a half -mile ferry ride from Delaware City to Pea Patch Island, where costumed interpreters transport visitors back to the summer of 1864. Photograph by Laura M. Lee

Kevin Mackie (left) with Jonathan Russ, UD associate pro- fessor of history. Russ served as Mackie's undergraduate adviser on the project. Photograph by Kathy F. Atkinson.

Kevin Mackie (left) with Jonathan Russ, UD associate pro- fessor of history. Russ served as Mackie's undergraduate adviser on the project. Photograph by Kathy F. Atkinson.

Pittsburgh heavy Artillery at Fort Delaware, summer of 1864. At one point, there were only 300 Union soldiers to guard nearly 12,000 Confederate prisoners. Lt. henry Warner is the officer (with sword) at left. others are unidentified. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of Delaware State Parks.

Pittsburgh heavy Artillery at Fort Delaware, summer of 1864. At one point, there were only 300 Union soldiers to guard nearly 12,000 Confederate prisoners. Lt. henry Warner is the officer (with sword) at left. others are unidentified. Photograph by John L. Gihon, courtesy of Delaware State Parks.

The 153rd military Police Company, Delaware Army National Guard, visited Fort Delaware as part of their annual training in summer 2009. Kevin mackie is in the front row, second from right. he and his brother, Brendan, de- ployed to Iraq in 2007–2008. Photograph by SFC mark P. Del Vecchio.

The 153rd military Police Company, Delaware Army National Guard, visited Fort Delaware as part of their annual training in summer 2009. Kevin mackie is in the front row, second from right. he and his brother, Brendan, de- ployed to Iraq in 2007–2008. Photograph by SFC mark P. Del Vecchio.

Prisoner letter from Fort Delaware, Oct. 26, 1864

Prisoner letter from Fort Delaware, Oct. 26, 1864

Distant view of Fort Delaware as seen from the river. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Distant view of Fort Delaware as seen from the river. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Prisoners are marched from Fort Delaware in a living history re-enactment of life at the fort. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Prisoners are marched from Fort Delaware in a living history re-enactment of life at the fort. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Fort Delaware's 8-inch Columbiad Cannon is still fired regularly during Heavy Artillery Demonstrations for Fort Delaware visitors. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.

Fort Delaware's 8-inch Columbiad Cannon is still fired regularly during Heavy Artillery Demonstrations for Fort Delaware visitors. Photograph courtesy of Doug Baker.