|

2:40 p.m., March 14, 2003--March 23, a University of Delaware professor will be watching with special interest to see how many Oscars the film “Chicago” takes home.

|

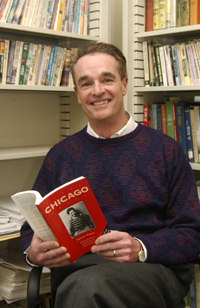

| Thomas Pauly, associate chair of the UD Department of English: “It’s an interesting look at the way that things, even murder cases, get merchandised, and how media-driven murder cases can turn the accused into celebrities,” |

Thomas Pauly, associate chair of the UD Department of English, is an expert on the original stage play “Chicago,” the 1920s murder cases on which it was based, and the young cub reporter, one of the first to reap the benefits of sensationalizing crime, who covered the trials and later suffered personal conflict after turning her journalistic endeavors into a play.

It’s safe to assume that the reporter, Maurine Watkins, who got her crime stories moved to the front pages of the Chicago Tribune by using humor and sensation, never envisioned the Broadway musical version of her play or the most recent film version with its 13 Academy Award nominations.

Pauly became intrigued by Watkins and the crimes that led to “Chicago” as part of his research into crime in the 1920s, the tabloids and the kind of reporters who wrote for them.

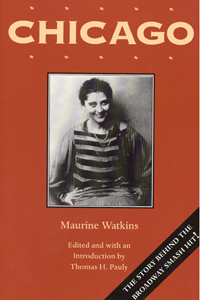

The result is his book, “Chicago,” published by Southern Illinois University Press, which contains Watkins’ 1927 play, as well as several of her articles that appeared in the Tribune in the early-to-mid 1920s.

“It’s an interesting look at the way that things, even murder cases, get merchandised, and how media-driven murder cases can turn the accused into celebrities,” Pauly said. “Maurine Watkins capitalized on ‘murder as humor.’”

Set against the background of the Roaring Twenties, the articles by Watkins sensationalized the cases of Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner, two women on Chicago’s “murderesses’ row” on charges of first-degree murder.

Gaertner, described as “a married cabaret singer with a long history of dalliances,” was charged with the fatal shooting of her boyfriend Walter Law, whom police found slumped over the steering wheel of Gaertner’s car.

Annan, jailed after shooting her lover, was known to have sat down to listen to one of her favorite jazz numbers on a phonograph before telephoning her husband to tell him that she had killed Harry Kalstedt to, as Pauly notes, “save her honor.”

Instead of covering the cases as garden-variety homicides, Watkins spiced her news stories up with touches of humor, recasting the pair as zany and stylish women who were more victims than murderers.

Readers were led into these stories with headlines such as, “Woman Plays Jazz Air as a Victim Dies” and “No Sweetheart Worth Killing—Mrs. Gaertner.”

This approach, Pauly said, got Watkins’ stories moved from the back to the front pages of the Tribune and may have played a role in the eventual acquittal of both women by evidently sympathetic all-male juries.

Pauly said that his research, which included tracking down the original articles in the Chicago Tribune, found that American society in the 1920s, at least as represented in major urban centers like New York City and Chicago, was interested in crime as entertainment.

“Reporters and other writers had begun to portray crime with a sense of humor,” Pauly said. “The public enjoyed and even expected this type of coverage.”

After the acquittal of both women, Watkins quit the Tribune, moved to New York, where she took an editorial position and enrolled in George Pierce Baker’s playwriting class at the newly opened Yale School of Drama. After the acquittal of both women, Watkins quit the Tribune, moved to New York, where she took an editorial position and enrolled in George Pierce Baker’s playwriting class at the newly opened Yale School of Drama.

The result was the play “Chicago,” which premiered in New York City on Dec. 30, 1926, to favorable reviews and an eventual run of 172 performances. In his introduction to “Chicago,” Pauly notes that the road version of the play was a hit in several other major cities and that “Chicago” eventually made it to the silver screen as a silent film in 1928 and became a hit for Ginger Rogers in the 1942 film “Roxie Hart.”

Roxie’s character was based on the real-life murderer Annan, while fellow “murderesses’ row” inmate Gaertner became Velma Kelly.

“What Watkins did was to take all the things she saw while covering the trials of both women and weave it into an interesting story,” Pauly said. “She used the notion of the criminal as the victim. The song ‘He Had It Coming,’ sung by Catherine Zeta-Jones in the role of Velma Kelly, typifies this attitude.”

The media-driven nature of the real-life trials of Gaertner and Annan was similar to the media-hype that surrounded the late 1990s trials of O.J. Simpson, Amy Fisher and the Mendendez brothers, Pauly said.

Although Watkins enjoyed her new status as the author of a hit play, she did not want it known that her articles may have led to the acquittal of murderers.

“When the play came out, she suppressed her newspaper past,” Pauly said. “She did not want people to know that she was seriously involved in the process she was making fun of in the play.”

Watkins was never able to repeat this success, and after a stint of work in New York City and Hollywood, she returned to her parent’s home in Florida around 1940 and lived a life of relative obscurity there until her death in 1969.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Pauly said, several Broadway producers wanted to convert the play into a musical, but all such efforts failed because Watkins, who had become a born-again Christian, refused to sell the necessary rights.

“I think she became more repentant as time went on because she felt she was the one who got them (Annan and Gaertner) off,” Pauly said.

Only after her death, were choreographer and producer Bob Fosse and actress Gwen Verdon able to secure the rights from her estate. Together with composers Fred Ebb and John Kander, they created the musical that reached Broadway in 1975.

Although the opening was upstaged by “A Chorus Line,” the play overcame mixed reviews and enjoyed a successful run. The musical still plays in regional theaters and recent revival is still playing on Broadway.

“I think the movie is pretty good,” Pauly said. “I think it will win a lot of Oscars.”

While Watkins eventually regretted her involvement in the original events upon which her play was based, Pauly said he is happy with the attention his book has received with the success of the movie.

“I don’t feet guilty about the success of the play and the attention it has given my book,” Pauly said. “In fact, I wish there were more of it.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photo by Kathy Flickinger

|