| 1. Introduction

In his famous Décadas del Mundo Nuevo (1530), the chronicler Pedro Mártir de Anglería bore out the heinous nature of the Amerindians by reporting a harrowing event that occurred in October 1513. In a Panamanian village, after slaughtering the chieftain of Quarequa and many of his warriors, Vasco Núñez de Balboa fed his fierce attack dogs with the flesh and bones of forty “Indians” accused of indulging in sinful acts of sodomy and idolatry as well as other abominable crimes. This event, quite common during European colonial expansion, served to exemplify the moral superiority of the conquerors over such barbarous behavior that ran contrary to established morality. Nevertheless, it is worth asking what kind of rational motivation could justify such a slaughter. What was the motive behind such ruthless annihilation perpetrated by the Spaniards? According to Pedro Mártir, the events occurred as follows,

This paragraph illustrates the methodical use of force during the first years of the Spanish conquest. Far away from any legal jurisdiction, the implementation of this cruelty was not based on an unrelenting coercion. Nor did these acts of cruelty and punishment disappear completely. The brutality of the massacres and the ravage of entire villages led by the official governors and their hunting mastiffs displayed an aggressive attitude that was executed in its purest and most radical form. And above all, it was periodically vented on the Indians not only because they could not offer any resistance, but also because they could never be degraded enough.2 Beyond Columbus’s perfunctory descriptions, the landscape of the New World proved to be, for the first royal historiographer of the Indies, the Spanish humanist Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, an inexhaustible source of knowledge and the main organizing principle in the first books of his Historia General y Natural de las Indias(1535)3. However, this popular image of a terrestrial paradise was soon superseded by a pessimistic view of corruption and wickedness. Unlike the peaceful Tainos, the warlike Caribs, well equipped with bows and darts, resisted the advance of the Spanish soldiers and indulged themselves in total licentiousness and even cannibalism. By 1540, however, while preparing a complete edition of the fifty books of his vast Historia, Fernández de Oviedo’s sensitivity toward his fellow countrymen’s social and moral conduct entailed a progressively sympathetic awareness of the tragic situation of the Amerindians, to the point of assigning them attitudes of Christian devotion. Drawing from the standpoints of post-colonial theory, what I propose in this article is to study the very different patterns of elaboration, enlargement, and reelaboration of Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia, rather than reduce his magnus opus to a mere instrument of political expediency. No doubt the emphasis on the negative and brutal aspects of the Spanish intervention obscures the coherence of Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia. His was not simply a propagandistic work, but a fractured, contradictory, and conflicting narrative. However, while mimetic violence against the Amerindians tends to presuppose a correspondence between the barbarism of the natives and the barbarism of the Spaniards, I shall argue that his criticisms also played a moralizing role, with the goal of better serving the interests of an imperialist project in which he completely believed. 2. The Offspring of the Devil

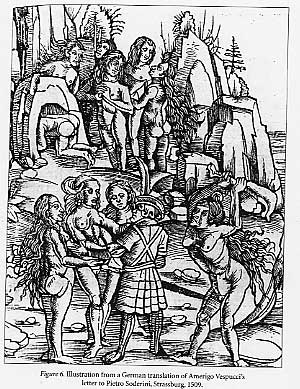

It is quite easy to discern the symbolical effect this picture had for Fernández de Oviedo. Lacking a cognitive vocabulary to apprehend native rituals, Fernández de Oviedo’s assumptions were founded on available images, such as demons incubus or succubus who fornicated licentiously with humans while they slept, witches, Sabbaths and the like, which allowed him to attribute, with total self-assuredness, evil actions to malignant spirits. Indeed, most of the chroniclers were so thoroughly imbued with a heterologous principle of negation that they looked at the social components of every single native society they found with profound skepticism10. The New World’s natives showed several behaviors that attacked the established morality, sapped the energy and determination of bodies, and corrupted its character. Those chroniclers agreed that the Indians lived imbued in an ongoing obscenity that controlled them totally. Not surprisingly, then, their evil actions were often attributed to an impure substance that smeared all they touched11. Of course, the one responsible for such festering antagonism was none other than Lucifer, the Prince of rebel angels, omnipresent figure in most of the chronicles and relations, who eagerly abducted the souls of the Indians and swooped them down. 3. Ambivalent Barbarity in the New World

Little wonder, then, that the Spaniards identified the presence of evil in the Indies and made it compatible with an ideal positive cosmovision. This neat division between those who chose God and good and those who chose the Prince of the Damned and evil had its explanatory advantages: namely, a convenient dualism with which to explain pagan cults. But what else could a Spaniard imagine after witnessing the “religious rites” that the natives willingly practiced, and that utterly offended those who could not avoid witnessing such “barbaric” behavior? Not surprisingly, a fetishizing connection quickly emerged between native religious practices and Spanish devils and witches which established a correlation between Satan’s wickedness and the Indians’ “ignorance and vileness”. Such perceptions were attenuated, however, as Fernández de Oviedo gradually admitted that a boundless lust for material wealth on the part of the Spanish conquerors was one of the main causes of the enormous havoc that was wreaked on the Indies12. By hunting and killing Indians in their spare time, Hernando de Soto, governor of Cuba, and his associates, Joan Ruíz Lobillo and Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa, were in fact instituting an aesthetic of horror that must have been studiously considered13. Noble status generally required legitimization through feats of bravery in battle. But de Soto belonged neither to nobility –Fernández de Oviedo said that “la verdadera nobleza y entera de la virtud se nasce”14– nor were his warfare activities worthy of receiving any military honor15. Those virulent acts meant, quoting Michael Taussig’s words, “the cannibalization of the cannibal”16. The target of these actions was, fundamentally, the physique of the natives. As a result of such a negation, the Amerindians were conceptualized as pure possessions. Violence appeared as “the mediator par excellence of colonial hegemony”17, and thus, the Indians became the physical prey over which the coercive power sought to leave an indelible mark. Thus, Columbus’ paradisiacal world was automatically transformed into a place wherein bestial men lived on the outskirts of civilization. The Spanish Crown had not yet secured its power in the decade of the 1530s. Thus, lacking any restraining power (the Viceroy, the Audiencia, secular clergy), Spanish conquerors could repeatedly attack native settlements to instill fear in the psyche of their enemies. Cannibal violence was a force on both fronts and thus became, to quote Michael Tausig again, “an addictive drug”18. If, as it seemed, no Edenic creatures inhabited the Indies, the Spaniards could emasculate the natives, or better still, consider them as simple objects of trade and enslave them. But unlike Pedro Mártir’s previously quoted report on the events of

1513, Fernández de Oviedo never engaged in any systematic execution

of certain groups among the native societies. Nor did he take pride in it19.

On the contrary, Fernández de Oviedo’s profound disillusionment and

distress about the Spanish civilizing scheme came as a result of the many orgies

of blood and fear perpetrated by the bulk of his fellow countrymen20.

By 1540, Oviedo’s harsh moral judgments did not focus as much on the barbarism

of the natives as on the savagery and depravity of the Spaniards. Above all,

Oviedo was concerned about the social fabric over which those warmongers must

base a long-lasting civil project of colonization.

In other words, it was not on the shoulders of the plebeian that the implementation of a model society should rest, according to Fernández de Oviedo. Nor should it depend on the priests21, or the university-trained lawyers, generically known asletrados22. Instead, Fernández de Oviedo relied on the noblemen23. Unlike de Soto, who was an upstart from Castilla de Oro, Nicaragua and Peru, Fernández de Oviedo was raised in an aristocratic milieu. Inculcated in the dominant culture, Fernández de Oviedo prided himself on being acquainted with prestigious artists and painters of the Renaissance, such as Leonardo de Vince and Andrea Mantegna24, as well as Kings and Popes, such as Frederick of Naples25 and Cesare Borgia26. A devotee of things aristocratic, it is no wonder, therefore, that Fernández de Oviedo considered himself much more competent than de Soto and other fickle and unstable officials of the same ilk to represent the interests of the Crown in the Indies. By the beginning of the 1540s, however, the tone of Fernández de Oviedo’s political discourse became more moderate as it became clear that no principle of aristocratic government had yet taken root in the Indies. Propagation of the gospel had not made great strides either, mostly due to the poor education and training of the priests who came to the New World27. Instead, the pillaging, violence and repression practiced by the Spaniards revealed the most depraved side of human conduct. According to Fernández de Oviedo’s account, some Spaniards had even wantonly engaged in acts of cannibalism28. From Columbus to López de Gomara, including Pedro Mártir and Fernández de Oviedo, cannibalism, along with native pagan rituals, provided the conquerors with a reality-based justification for waging war against the native Amerindians and enslaving them. By transgressing their own moral limits, the transformation of the Spaniards into man-eaters bluntly blurred human classification, putting them at the same level as the subhuman savages. With the disclosure of such scandalous acts, Fernández de Oviedo's characterization of the Spaniards created, in time, a more sinister image. As already noted, Fernández de Oviedo’s encyclopedic curiosity played a fundamental role not only in conveying the goodness of nature, but also in dismissing all the evil it contained. The subsequent lack of harmony and cohesion in his narrative was the result of juxtaposing the meaning and scope of God’s nature with the diabolical. But that strategy was unavoidably doomed to failure. Writing in the context of the New Laws of 1542, designed to curb the leading role of the encomenderos, and ultimately, to set limits on the collection of tribute, Fernández de Oviedo shifted progressively into a far more pessimistic view of the human condition, which included not only those who were judged to be deviant, imperfect, or marginal, but also the insatiable greed, cold-blooded cruelty and despotism of his fellow countrymen29. In effect, this perception, as articulated by a critical consciousness, offered

a very different representation of the American reality that had little to

do with the ideology of the repressive apparatus of the state30.

Nature’s treasure hoards of marvels now became a secondary issue. Far more

focused on historical events than ever, Fernández de Oviedo’s natives

became a much more welcoming, noble and peaceful people than ever, but above

all, they became moral subjects endowed with the power of speech and able to

voice Fernández de Oviedo’s most profound disenchantment to his readers

as follows:

From the standpoint of literary criticism, Kathleen A. Myers has clearly demonstrated that the use of direct discourse, instead of indirect discourse, is not accidental in Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia. Following Mikhail Bakhtin’s reflections on the use of dialogue as an ideological weapon, Myers fully examined the use of the first person singular in Book XXXIII, Chapter LIV, whith the goal of correcting the inaccuracies of other chroniclers in order to arrive at an objective truth. By manipulating the utterances of the Indians, the role of Fernández de Oviedo as participant-observer was decisively heightened, placing him in a dialogical dimension that allowed him to express his own point of view without loosing control of the text32. From this privileged position, Fernández de Oviedo, achieved two objectives: he partially acquitted himself of any responsibility for the actions of his fellow countrymen while still appearing as the protector of the Crown’s interests. Viewed in these terms, this passage reveals a new discursive turn which does not precisely extol the deeds of the Spaniards or their dogs of war. On the contrary, Fernández de Oviedo attempted to pit his readers’ moral code against Spanish cruelty and despotism33. The differences between Europeans and Amerindians lessened as the threshold of violence began to be systematically crossed. The Indians were barbarous, but in no way were they less loathsome than some Spanish conquerors, ministers of their victorious God, whose factional wrangles had betrayed the Christian principles upon which the colonization process was based. In his dialogue with Hernando de Soto, the chieftain Casqui was not mocking him, but rather presenting Fernández de Oviedo’s inner dilemma. How could the Spaniards, openly betraying Christian tenets by hunting down the Indians for sport in the name of God, defend and practice such a moral contradiction--Christian charity combined with infinite cruelty--in the Indies? Was the Dominican Bartolomé de Las Casas correct in characterizing the Indians as lambs defenseless against the cruelty of wolves and lions? Was Christian “civilization” responsible for sowing corruption, greed and other evils in the New World? Thus, I argue, that Fernández de Oviedo's desire to reflect objectively on paper what he rejected morally, whether the amoral behavior of the Spaniards or the Indians, produced a great tension between rhetoric and logic, that is, between what the text intended to communicate and what it was nonetheless constrained to hide. A distinguishing characteristic of the human condition, according to Cicero, is the capacity for dialectic interaction34. So, how was it possible now for those very same Amerindians who had been heretofore ridiculed as “thick skulls” (cascos duros) to exonerate themselves through the use of words as symbols? In Marcel Bataillon’s view, Fernández de Oviedo’s stark historical pessimism was greatly influenced by that oracle of modern times, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469?-1536)35. As a result, the aporias of the chronicler’s narrative gave rise to an intellectual skepticism with regard to Spain’s project of civilization. Nevertheless, Fernández de Oviedo’s attitude was always that of an official of the Royal Crown in tune with Erasmian intellectuals, such as the Emperor’s secretary, Alfonso de Valdés (Diálogo de las cosas ocurridas en Roma, 1529) and Cristóbal de Villalón (Diálogo de Mercurio y Carón, 1528-1530; El scholastico, 1538). However daunting the conquerors’ brutalities might be, the Crown-appointed chronicler and warden of the fort of Santo Domingo never gave up thinking of European values as the civilizing framework that could--and should-- regenerate the New World. The spiritual conversion that Fernández de Oviedo is believed to have experienced by 1546, according to José Rabasa, did not really alter his perception of the evil nature of the native population at all. Strictly speaking, Fernández de Oviedo’s condemnation of de Soto had much less to do with a “change of heart” than with the new legal framework introduced by the “New Laws of the Indies”36. I would like to examine this argument more closely in the light of this documentary evidence. In this legal context, Fernández de Oviedo had no other option--and this he did both deftly and persuasively--than to follow suit, and therefore, he yielded to the Crown’s need to regulate both the human and material resources of the Indies. With the introduction of a new political climate which sought to abolish the encomienda and reinstate the Indians’ right to their own land, Fernández de Oviedo was able to seize the occasion to accuse “bad Christians” of committing cruelties against the native population without running the risk of contradicting himself37. By 1546, Fernández de Oviedo, accompanied by the experienced colonial official, Alonso de Peña, departed for Spain to protest the harshness and arbitrary behavior of the governor of Guatemala, Alonso López de Cerrato, named to preside over the recently established Audiencia for much of Central America (Los Confines)38. As solicitors or agents for the city of Santo Domingo and the island of Hispaniola, they also indicted the resident judge in charge of implementing the New Laws in Hispaniola, as being unsympathetic to the needs of numerous colonists and traders, including Fernández de Oviedo himself. Clearly enough, it would not have been wise to raise such accusations ten years earlier while still in the Indies. In several letters sent the Spanish king (1537), Fernández de Oviedo pointedly mentioned the festering antagonism between the factions of Francisco Pizarro (1475?-1541) and Diego de Almagro (1475-1538) over possession of the rich city of Cusco. As one of the legal representatives of the latter in the court, Fernández de Oviedo had little sympathy for the former39. As a matter of fact, Oviedo displayed a profound hatred of the Pizarro clan, and especially of Hernando Pizarro, whose success irritated Fernández de Oviedo profoundly40. Yet, although the chronicler’s support for Almagro loomed large in several letters, no false accusations were delivered against Pizarro’s clan. Instead, Fernández de Oviedo’s strongest accusations were against the royal civil servants or letrados who were progressively dominating the governmental bureaucracy of sixteenth-century Spain. Most of them, Fernández de Oviedo claimed, lacked the most rudimentary experience necessary to deal tactfully with the problems of the Indies41. And to make things worse, he warned, they had caused so much havoc in Peru that the rest of Spain’s possessions the New World could be ruined as well42. From 1540 onwards, a new political opportunity enabled Fernández de Oviedo to resort to other models and narrative strategies to highlight the evil deeds of his compatriots while staying within the parameters of the Christian canon. Hence, the Erasmian influence should not be simply regarded as an ideological instrument to obtain political favors. Fernández de Oviedo’s Erasmianism, it has been established, was not so much a well-defined creed, as it was a great spiritual force behind the imperial vision of Charles V which was used to readjust the Spanish colonial project. For only the Emperor’s august intervention, backed by his most loyal knights and officials, could end to the fragmentation of the colonial society, reform bad habits and revitalize a mistreated land43. As the legal representative of God on Earth and the preserver and dispenser of justice, Charles V came to be considered what Cicero called the moderator republicae. He played, according to the Roman-Spanish tradition, the role of arbiter among opposig interests and groups in conflict. In the performance of this public task, the monarch was expected to enact laws in line with the principles of Christian justice and equity. To preserve this legal fiction he had to make himself accessible to all his subjects. In this respect, the Crown became a paternalistic symbol for those who, like Fernández de Oviedo, sought the redress of some grievance or the protection of his interests which were the same as those of the King. Chapter XXXIV of Book XXIX, completed by 1548, neatly summarizes Fernández de Oviedo’s preoccupation with the misgovernmentof the New World. In the light of a reformed Christian empire, the author undertook a general revision of Spain’s ascendancy in the Indies44. The objective is twofold. On the one hand, Fernández de Oviedo highlighted the lack of institutional organization of the civilizing project. On the other hand, instead of limiting the access to Castilians, as Queen Isabel had recommended, other important fringe groups, like the Catalans, the Basques, the Galicians and the Portuguese had access to the Indies, thus altering the homogeneity of the original plan45. In most parts of the Indies, the Crown had little or no effective control over its subjects. Without any law-enforcing machinery able to regulate their actions, the conquerors indulged their personal aspirations. According to Fernández de Oviedo, Pedrarias Dávila, the governor of Panama, and his associates, together with a sundry array of Spanish soldiers and ambitious priests, were alike responsible for having plunged the New World into chaos. Evincing a clearly moralistic bent, Fernández de Oviedo’s intention was not simply to denounce the Crown’s complicity in tolerating such bloody wrangles. On the contrary, the aged historian of His Imperial Majesty was suggesting the adoption of the aristocratic model of settlement he himself had designed in 1520. This model sought primarily to monopolize physical violence, and thus set the stage for a pacified social space presided over by the monarchy46. One of the functions of the universal monarch, to follow Erasmus’s reasoning, was to preserve the peace and welfare of all Christendom47. But Charles V was at war with powerful enemies, so that Fernández deOviedo’s critique could not be taken to extremes. Echoing paradoxically the claims of las Casas against “los tyranos alemanes que an estado y están en los reynos de Veneçuela”48, Fernández deOviedo’s patriotic zeal led him to blame other nations as well, “pues griegos e levantiscos e de otras nasciones son incontables”49. In truth, many Greeks could be found operating in the Indies predominantly as sailors in the decade of the 1540s. Sicilians, Milanese, Germans and Flemings were not unknown either, especially after the coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. Spain was seen and described more explicitly as part of a heterogeneous empire, and consequently, all its subjects were given permission to go to the Indies (1525), even though they were not from the Castilian-speaking community. But what was worse, according to Fernández de Oviedo was that a large number of those foreign sailors were also reputed to be undisciplined and cruel50. At a discursive level, a sort of xenophobic attitude ran counter to such a linguistic and cultural heterogeneity. All things considered, Fernández de Oviedo’s hatred of de Soto’s cruelty, arrogance and military incompetence did not turn the Amerindians into better subjects or “good indians”. Nor did he absolve the Indians of all their sins. Upon placing the blame on the Spaniards, Fernández de Oviedo’s discursive narrative returned to the initial categorization of “barbaric” and “uncivilized” native peoples. The noble and peaceful image he had momentarily portrayed, in contrast to de Soto’s senseless violence, was not just another scriptural device to pass judgement on the evil actions of his countrymen. Apparently, those Amerindians living in the Caribbean islands seemed to be endowed with a basic nature quite similar to that of Europeans, though Fernández de Oviedo was never convinced of it. Indeed, for him, the native inhabitants continued to be mostly idle, vile people, who lacked general understanding51. For this reason, by moderating his harangues against Hernando de Soto’s phobic practices, Fernández de Oviedo’s narrative seemed to return to its point of departure. The Indians, not the Spaniards, were again responsible for their own moral ruin. His about-face from the most exuberant pleasure to remorse did not make him relapse into a subversive interpretation of Christian order. Given that he always persisted in his profound contempt against those “brutes” who lacked any vestige of culture, his critical consciousness did not make the Court-chronicler loose the thread of continuity of his monumental Historia. By being consistent with his original point of view, Fernández de Oviedo achieved anew a great deal of coherence as imperial chronicler. 4. Conclusion

As Antonello Gerbi put it, truth was always Fernández de Oviedo’s supreme deity53. In the footsteps of Pliny’s previous work, the Spanish chronicler accepted the model of a general compilation and of a natural history, but he rejected the written sources of the Greek historian and replaced them with his own direct experience54. Unlike Columbus’ clumsy reports, Fernández de Oviedo’s unrestrained curiosity provided a kaleidoscopic view of the nature of the New World, thereby inaugurating a methodical questioning and desire for (pre)scientific knowledge55. But in the pursuit of that divine truth, the loyal administrator, besides pleasing a contemporary audience fervently interested in reading accounts of a world so vast and stupefying, unveiled the flaws of the colonial project he was supposedly to defend. In many, if not most, respects, Fernández de Oviedo was certainly very critical of the colonization process. But obviously, the gadfly role he played throughout the last chapters of his Historia was not compatible with his origianl goal. Instead of criticizing the Crown’s imperial policies and those who carried them out, Oviedo recovered the central theme of his imperialist discourse by attacking the “barbarous” natives and the runaway black slaves, putting them all at the extremes of human behavior56. Endnotes

2 As Elaine Scarry pointed out, “torture aspires to the totality of pain” (Body in Pain. The Making and Unmaking of the World, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, pp. 55). On the nature of terror and the strategic function of torture, see especially Chapter 1, “The Structure of Torture: The Conversion of Real Pain into the Fiction of Power”, pp. 27-60. Return to reading. 3 Antonello Gerbi, Nature in the New World. From Christopher Columbus to Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, (Pittsburgh, [1975] 1985); Edmundo O’Gorman, Cuatro historiadores de Indias, (Mexico, 1979); Manuel Ballesteros Gabrois, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, (Madrid, 1981); Stephanie Merrim, “Un Mare Magno e Oculto”: Anatomy of Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia General y Natural de las Indias”. Revista de Estudios Hispánicos (1984); Merrim, “The Aprehension of the New in Nature and Culture”, in René Jara and Nicholas Spadaccini, eds, 1492-1992: Re/Discovering Colonial Writing, Hispanic Issues, Volume 4, The Prisma Institute, 1989; Merrim, “The First Years of Hispanic New World historiography: the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America”, in Roberto González Echevarría and Enrique Pupo-Walker, eds, The Cambridge History of Latin American Literature. Volume I, Discovery to Modernism (Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 79. Return to reading. 4 Alexandre Coello de la Rosa, “Representing the New World’s Nature: Wonder and Exoticism in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés”. Historical Reflection/Reflexions Historiques, Special Issue, Vol. 28 (1), Forthcoming Spring, 2002. Return to reading. 5 Stephen J. Greenblat, Marvelous Possessions. The Wonder of the New World (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992), pp. 14. Return to reading. 6 On the issue of witch-hunting activity in Toledo (1513), Cuenca (1515), Aragon and Castile (1520), and especially, Navarre (1527-1528), see the classic work of Henry Kamen, Inquisition and Society in Spain in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), pp. 198-218. Return to reading. 7 As Clifford Geertz put it, “culture is not a power, something to which social events, behaviors, institutions, or processes can be causally attributed; it is a context, something within which they can be intelligibly - that is, thickly - described” (The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, 1992, pp. 14). Return to reading. 8 Francisco López de Gomara, Historia General de las Indias (Barcelona: Iberia, Volume I, [1569] 1954), pp. 49-51. Return to reading. 9 Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Historia General y Natural de las Indias [hereafter, Historia], (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, Vol. 119, Bk. XXIX, Chapt. XXXII, [1535, 1557] 1959), pp. 342). Return to reading. 10 I have borrowed the term ‘heterology’ from Michel de Certeau: “Travel narratives of the French to Brazil: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries”. Representations, “The New World”, 33 (1991). Return to reading. 11 Julio Caro Baroja, Las Brujas y su mundo (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, [1966] 1995), pp. 172. Return to reading. 12 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 118, Bk. XVII, Chapt. XXII, 1959, pp. 342. Return to reading. 13 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 118, Bk. XVII, Chapt. XXIII, 1959, pp. 156. Return to reading. 14 Oviedo, Quinquagenas I (Las Memorias de Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Edited by Juan Bautista Avalle-Arce, Chapel Hill: North Carolina Studies in the Romance Languages and Literatures, [1555] 1974), pp. 22. Return to reading. 15 To Oviedo’s dismay, though, Soto obtained in 1539, while in Spain, fame and recognition from the Emperor in gratitude for his services in Peru (Historia, Vol. 118, Bk. XVII, Chapt. XXI, 1959, pp. 152). Return to reading. 16 Michael Taussig, Shamanism, A Study in Colonialism, and Terror and the Wild Man Healing (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987, pp. 107). Return to reading. 17 Ibid, 5. Return to reading. 18 Ibid, 105. Return to reading. 19 Alberto Salas, “Fernández de Oviedo, crítico de la conquista y de los conquistadores”. Cuadernos Americanos 2, Volume LXXIV (1954), pp. 161. As Antonello Gerbi points out, “Oviedo was a vecino, a resident or householder, one of the first vecinos of the Indies, a tax official, administrator, local magistrate, a businesman, and not a military man” (1985, pp. 245). Return to reading. 20 Juan Pérez de Tudela Bueso, Introduction to Oviedo’s Historia, 1959, LVI-LVII. Return to reading. 21 In the Epistola del Almirante don Fadrique Enríquez (1524), Oviedo sharply criticized the monastic orders, accused of having lost their original purity (Cited in Edmundo O’Gorman, Sucesos y Diálogo de la Nueva España, Mexico: Ediciones de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Imprenta Universitaria, 1946, XI. The manuscript is held in the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, Manuscript 7075, fols. 13-44). Return to reading. 22 This disparagement for the new colonial administrators - which goes back to 1507, when he was a court clerk - was steady throughout Oviedo’s life. It had to do assuredly with Oviedo’s self-taught nature and his emphasis on vital experience (Pérez de Tudela Bueso, Introduction to Oviedo’s Historia, 1959, XIX). Return to reading. 23 Demetrio Ramos Pérez, “Las ideas de Fernández de Oviedo sobre la técnica de colonización en América”. Cuadernos hispanoamericanos, Revista mensual de cultura hispánica, 95 (Nov. 1957), Madrid, pp. 279-289; Pérez de Tudela Bueso, 1959, LXVIII; María Molina de Lines & Josefina Piana de Cuestas, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo: Representante de una filosofía política española para la dominación de Indias (Escuela de Historia y Geografía, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Costa Rica, 1978), pp. 16. Return to reading. 24 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 119, 1957, pp. 7 (Prologue to the Book X). Return to reading. 25 Oviedo, Quinquagenas II, [1555] pp. 1974, 368-371; Quinquagenas III, [1555] 1974, pp. 623-625. Return to reading. 26 Oviedo, Quinquagenas I, [1555] 1974, pp. 97-98. Return to reading. 27 According to the letter sent to Charles V in May 31, 1537, Oviedo grumbled about the deficient evangelization in Santo Domingo, mostly due to the lack of parishes and strong opposition of the priests whom he charged with using the wealth of the Church for personal benefit instead of public worship. Thus, he pointed out that “(...) é estos padres clérigos en les apuntar que haya otras parroquias, luego saltan é dan gritos, porque se lo quieren tragar todo, é no veo en esta ciudad ricos sino á los clérigos” (Colección de Documentos Inéditos de América y Oceanía, Volume 1, Madrid, 1864, pp. 549). See also his Batallas y Quinquagenas (Ediciones de la Diputación de Salamanca, Salamanca, [1550-1552], 1989), pp. 445-447. Return to reading. 28 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 119, Bk. XXVIII, Chapt. VI, 1959, pp. 191-194. Return to reading. 29 Juan Pérez de Tudela Bueso, 1959, CXXXIV. For a similar analysis, see José Rabasa, “The Representation of Violence in the Soto narratives”, in The Hernando de Soto Expedition. History, Historiography, and “Discovery” in the Southeast, edited by Patricia Galloway (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), pp. 394. Return to reading. 30 For Santa Arias, historiography functioned in the sixteenth century simply as an ideological apparatus that either legitimated and perpetuated the politics of the state or served as an instrument of political intervention and reform (“Empowerment Through the Writing of History. Bartolomé de Las Casas’s Representation of the Other(s)”, in Early Images of the Americas. Transfer and Invention, edited by Jerry M. Williams and Robert E. Lewis Tucson & Arizona, The University of Arizona Press, 1993, 163). This reductionist approach is extremely simplistic, besides false, because Oviedo’s Historia, while imperialist in style and proportion, went through so many changes, though, that it makes difficult a classification in such a Machiavellian terms. Return to reading. 31 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 118, Bk. XVII, Chapt. XXVIII, 1959, pp. 179. Return to reading. 32 Kathleen A. Myers, “History, Truth and Dialogue: Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia general y natural de las Indias (Bk XXXIII, Ch LIV)”. Hispania, 73 (1990), pp. 617. With respect to this moral universe within which the Indian becomes a critic, see also the suggestive article of Anthony Pagden, “The Savage Critic: Some European Images of the Primitive”. The Yearbook of English Studies, “Colonial and Imperial Themes”. Special Number, Modern Humanities Research Association, King’s College, London, (1983), pp. 32-45. Return to reading. 33 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 117, Bk. XVI, Chapt. XI, 1959. Return to reading. 34 Cicero, De natura deorum (translated by H. Rackham, Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press, Volume II, 1933), pp. 267. Return to reading. 35 The thought of the leading Catholic reformist of the age, the humanist Erasmus penetrated and rooted with astonishing force among some sectors of the Castilian elite (Marcel Bataillon, Erasmo y España. Estudios sobre la historia espiritual del siglo XVI”, Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, [1937] 1966, pp. 642. In his Batallas y Quinquagenas (1550-1552), Oviedo highly praised the work of Erasmus; in particular, De la ynstitución del príncipe christiano or Enquiridión (1989, pp. 31). As an illustration of how much ingrained Oviedo was in the thought of Erasmian humanism, E. Daymond Turner successfully identified various of Erasmus’s books that Oviedo kept – both in Spanish and in Latin language - in his private library in Santo Domingo (Los Coloquios, Sevilla, Juan Cromberger, 1529; Instituto Principis Christiani, Basilea, J. Frobenius, 1518; La Legua de Erasmo, Toledo, Juan de Ayala, 1533, and Sevilla, Juan Cromberger, 1534; Libro del Aparejo que se deue hazer bien morir, Burgos, 1535), favoring a growing permeability to Erasmian ideology (Madrid, 1971). Return to reading. 36 Profoundly influenced by Las Casas’ Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1542), the emperor Charles V signed the so-called New Laws on November 20, 1542. These laws were an unusual combination of Christian humanitarianism and practical politics. Their primary purpose was to put an end to the encomienda system, or, perhaps more accurately, bring the encomiendas under the direct jurisdiction of the crown. This would both free the Indians from exploitation and prevent the growth of a new quasi-feudal elite, barring the transfer of current grants, including by inheritance. On Oviedo’s down-to-earth common sense as for the new context that emerged with the New Laws (1542), see Juan Pérez de Tudela Bueso, 1959, CXXXIV. For a similar analysis, see José Rabasa, “The Representation of Violence in the Soto narratives”, in The Hernando de Soto Expedition. History, Historiography, and “Discovery” in the Southeast, edited by Patricia Galloway (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), pp. 394. Return to reading. 37 Las Casas returned to Spain in 1540. Along with other churchmen and laymen, he began to lobby in favor of the Indians at the court of the Emperor. Shortly after, the claims for returning the “Indians”’s properties appeared in his Representación al Emperador Carlos V (1542). As a result of this intellectual fermentation, Las Casas, along with his Dominican brothers, expressly demanded the abolishment of the encomienda as a private institution on the famous Memorial de Remedios (1542). The flurry of his bureaucratic activity during 1540-1544 ultimately demonstrates how besieged the Crown was, groping for some solution to the New World’s dismal future. Return to reading. 38 José Miranda, Introduction to Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Sumario de la natural historia de las Indias (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica [1950] 1979, pp. 35). According to Enrique Otte’s analysis, López de Cerrato did not take care for the fortification’s defense under Oviedo’s custody. This was the principal reason, in Otte’s view, for Oviedo’s disapproval (“Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, alcaide”, in Francisco de Solano & Fermín del Pino (eds.), América y la España del siglo XVI, Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, C.S.I.C, 1982, pp. 42). Return to reading. 39 On June 18, 1535, Almagro granted powers of attorney to Gonzalo Hernandez de Oviedo for establishing an entail and arranging a marriage for the young Diego de Almagro (The Harkness Collection in the Library of Congress, Documents from Early Peru. The Pizarros and the Almagros, 1531-1578, Documents nº 81-82). Return to reading. 40 In the course of the decade of 1550, however, Oviedo openly portrayed Pizarro and his brothers as tyrants, killers of princes and traitors to the Spanish crown (Quinquagenas I, [1555] 1974, 32-33; 168-170). Charles V did not kill Francis I of France while he was imprisoned in Madrid (1525). Instead, Francisco Pizarro, a bastard, murdered the Inca prince Atabaliba with no mercy, arousing a great repulse (Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 121, Bk. XLVI, Chapt. XXII, 1959, pp. 121-124; Quinquegenas II, pp. 265-266; Licentiate Espinosa to the secretary of the Emperor, Francisco de Los Cobos, October 1st, 1533, in Colección de Documentos Inéditos de América y Oceanía, Volume 42, Madrid, 1884, pp. 74-75). Naturally, Pizarro’s secretary, Francisco de Xerez, in his Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú y provincia del Cuzco, llamada Nueva Castilla (1534), justified it. So, too, did Pedro Pizarro: “porque hera ynposible soltándole ganar la tierra” (Relación del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú, edited by Guillermo Lohmann Villena & Pierre Duviols (Lima-Peru: Pontificia Católica Universidad del Perú, Fondo Editorial, [1571] 1978), pp. 62). Return to reading. 41 In another letter to Charles V, dated December 9th, 1537, Oviedo openly blamed those letrados for having ruined a true partnership that had lasted for many years. This kind of criticism is recurrent in Oviedo’s work (Batallas y Quinquagenas, [1550-1552] 1989, pp. 446-447). Interestingly enough, Oviedo did not blame the letrados, justicias or juezes directly in his Historia. As thinking of Pizarro’s and Almagro’s enmity, the Spanish chronicler ambiguously alluded to “la industria de los malos terceros”, but without charging anybody in particular (Historia, Volume 121, 1959, pp. 212 (Prologue to the Book XLVIII). Return to reading. 42 Colección de Documentos Inéditos de América y Oceanía, Volume 1, Madrid, 1864, pp. 532-533. According to another letter to the Emperor dated October 25, 1537, Oviedo stated that “caballero ha de ser é hombre de buena conciencia é esperiencia, é no neeesitado, el que suele acertar en tales negocios é no tanto papel ni escribanos, sino un buen natural é persona que haya visto muchas cosas en la paz é en la guerra” (Colección de Documentos Inéditos de América y Oceanía, Volume 1, Madrid, [1864] 1966, pp. 528). Return to reading. 43 Oviedo, fully convinced of being in possession of truth, felt morally compelled to unmask undesiderable associates, especially those sycophantic flatterers who did not serve their monarch, but themselves. He defined kingship according to the Castile’s legal tradition. The great compilation of Las Siete Partidas (dating ca. from 1256 to 1263 and promulgated in 1348) of Alfonso X, which provided Oviedo with the ideological model of vassal and his monarch united in the common enterprise of defending the Crown against selfish interests: loyalty and service in return for justice and leadership. Understood in such a manner, Oviedo contended that “bien conozco que algunos me culparán en lo que he escripto (...); pero mirad, letor, que también yo he de morir, e que me bastan mis culpas sin que las hagan mayores, sino escribiese lo cierto, y entended que hablo con mi Rey, e que le he de decir la verdad. E lo aviso para que provea en lo presente e por venir, para que Dios sea mejor servido e Su Magestad (...)” (Historia, Vol. 119, Bk. XXIX, Chapt. XXXIV, 1959, 354. The emphasis is mine). Again, Oviedo bore in mind another work of Erasmus when writing these words: De praeparatione ad mortem (1534), which was translated into every major European language and of which the official chronicler held a copy in his personal library. Return to reading. 44 By 1548, other historians followed suit. For instance, the chronicler Pedro de Medina (1493-1567) did not locate the Hesperides in the Indies, but much closer: in the Canary islands (Libro de grandezas y cosas memorables de España, in Obras de Pedro de Medina, edited by Angel González Palencia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid, 1944, pp. 68). Return to reading. 45 As Oviedo put it, almost peevishly, “qué queréis que se esperase de tantas diferencias e gentes e nasciones mezcladas e de extrañas condiciones como a estas Indias han venido e por ellas andan?” (Oviedo, Historia, Volume 119, Book XXIX, Chapter XXXIV, 1959, 355). However, other chroniclers, like Pedro de Medina, spoke of Spaniards and Spanish deeds to refer to “the discovery of many islands and peoples of different nations in the New World” (1944, pp. 44). Return to reading. 46 Stephanie Merrim, 1984, pp. 113-114. Return to reading. 47 Erasmus, Enchiridion or The Education of a Christian Prince [Institutio Principis Christiani], edited by Lester K. Born (New York: Octagon Books, [1503] 1973), pp. 249-257. See also, on various aspects, Erasmus’s Querela Pacis. Return to reading. 48 In 1524, under pressure from German banking houses, German merchants were allowed to trade with the Indies, but not to settle in them. The results, according to Las Casas, were simply appalling (Bartolomé de Las Casas, Memorial al Emperador, cited in Bartolomé de Las Casas, Obras Completas. Cartas y Memoriales, Volume 13, [1543] 1995, pp. 154). Return to reading. 49 Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 119, Bk. XXIX, Chapt. XXXIV, 1959, 355. See also his Quinquagenas I [1555] 1974, 167. Return to reading. 50 James Lockhart, Spanish Peru, 1532-1560. A Colonial Society (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1968), pp. 114-134. Return to reading. 51 In this instance, Oviedo pointed out that “ni tampoco es aquesto sólo la causa de la destruición e asolación de los indios, aunque harta parte para ello ha causado esta mixtura; mas, juntos los materiales de los inconvenientes ya dichos, con los mesmos delictos e sucias e bestiales culpas de los indios sodomitas, idolatrías, e tan familiares e de tan antiquísimos tiempos en la obidiencia e servicio del diablo, e olvidados de nuestro Dios trino e uno, pensarse debe que sus méritos son capaces de sus daños, e que son el principal cimiento sobre que se han fundado e permitido Dios las muertes e trabajos que han padescido e padescerán todos aquellos que sin baptismo salieron desta temporal vida” (Oviedo, Historia, Vol. 119, Bk. XXIX, Chapt. XXXIV, 1959, 355). Return to reading. 52 Oviedo, Quinquagenas II, [1555] 1974, 299. For further details on the same event, see also Historia, Vol. 120, Bk. XLII, Chapt. XI, 1959, pp. 419. Return to reading. 53 Antonello Gerbi, [1975] 1985, pp. 216. Return to reading. 54 Quinquagenas III, [1555] 1974, 418. Return to reading. 55 José Antonio Maravall, Antiguos y modernos. La idea de progreso en el desarrollo inicial de una sociedad (Madrid: Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones, Madrid, 1966). Return to reading. 56 From 1546 onwards, Oviedo began to account

for numerous riots of black slaves in Santo Domingo. Similar to those Caribs,

the black rebels were judged to be warlike, treacherous and non-civilized and

consequently, they were worthy of being enslaved by the Spaniards (Quinquagenas

II, [1555] 1974, 291-294; 372-373). Return to reading.

|

||||||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALMAGRO, Diego de. The Harkness Collection in the Library of Congress, Documents from Early Peru. The Pizarros and the Almagros, 1531-1578. Documents nº. 81-82. ARIAS, Santa. “Empowerment Through the Writing of History. Bartolomé de Las Casas’s Representation of the Other(s)”. in WILLIAMS, Jerry M. and LEWIS, Robert E (eds.), Early Images of the Americas. Transfer and Invention. Tucson & Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 1993. BAKHTIN, Mikhail M. Epic and Novel. En The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist, Austin & London: The University of Texas Press, 1981. 444 p. BALLESTEROS GABROIS, Manuel. “Fernández de Oviedo, etnólogo”.

Revista de Indias, 1957, nº 69-70.

BATAILLON, Marcel. Erasmo y España. Estudios sobre la historia espiritual

del siglo XVI”. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, [1937] 1966, 921

p.

BOLAÑOS, Álvaro Félix. “El primer cronista de Indias

frente al “Mare Magno” de la crítica”. Cuadernos Americanos, 1990, Vol.

20, nº 20, pp. 42-61.

CARO BAROJA, Julio. Las Brujas y su mundo, Madrid: Alianza Editorial, [1961] 1995. CICERÓN, Marco Tulio. De natura deorum / Academica. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1956, 663 p. COELLO DE LA ROSA, Alexandre. Representing the New World’s Nature: Wonder and Exoticism in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. Historical Reflections/Reflexions Historiques, Vol. 28, nº 1, Spring 2002. COLECCIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS INÉDITOS RELATIVOS AL DESCUBRIMIENTO, CONQUISTA Y COLONIZACIÓN DE LAS ANTIGUAS POSESIONES ESPAÑOLAS DE AMÉRICA Y OCEANÍA, Madrid: Imprenta de Frías y Compañía, Editados por Luís Torres de Mendoza, 1864-1884. COLÓN, Cristóbal. Diario de a bordo. Madrid: Historia 16, Crónicas de América, nº 9, 1992. DE CERTEAU, Michel. “Travel narratives of the French to Brazil: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries”. Representations, 1991, n° 33. ERASMO DE ROTTERDAM. El Enchiridion o manual del caballero cristiano [Institutio

Principis Christiani]. Edited by Dámaso Alonso and preface by Marcel

Bataillon. Madrid: [1503] 1932.

FERNÁNDEZ DE OVIEDO, Gonzalo. Epistola del Almirante don Fadrique Enríquez.

Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, Manuscript 7075, Sheets 13-44, 1524.

FOUCAULT, Michel. The Politicts of Truth, New York: Semiotext(e), 1997, p. 240. GEERTZ, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, New York, [1973] 1992. GERBI, Antonello. La naturaleza de las Indias nuevas: de Cristóbal

Colón a Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Mexico: Fondo de Cultura

Económica, 1975, 562 p.

GREENBLAT, Stephen J. “Resonance and Wonder”. Bulletin of the American Academy

of the Arts and Sciences, 1990, nº

43.

KAMEN, HENRY. Inquisition and Society in Spain in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985. LAS CASAS, Bartolomé de. Carta al Consejo de Indias. En Obras Completas.

Cartas y Memoriales. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, Vol. 13, [1531] 1995, 439 p..

LEVITICUS. Cambridge University Press, London – New York – Melbourne, 1976. LOCKHART, James. Spanish Peru, 1532-1560. A Colonial Society. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1968, 285 p. LÓPEZ DE GOMARA, Francisco. Historia General de las Indias. Barcelona:

Iberia [1569] 1954.

MARAVALL, José Antonio. Carlos V y el pensamiento político del

Renacimiento. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos, 1960, 332 p.

MÁRTIR DE ANGLERÍA, Pedro. Cartas sobre el Nuevo Mundo. Madrid:

Ediciones Polifemo, [1530] 1990, 149 p.

MÉNDEZ, Angel Luís. Estudio y análisis del discurso narrativo en la Historia general y natural de las Indias de Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. Doctoral Dissertation, New York University, 1992. MERRIM, Stephanie. “Un Mare Magno e Oculto”: Anatomy of Fernández de

Oviedo’s Historia General y Natural de las Indias”. Revista de Estudios Hispánicos,

Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1984, pp. 101-111.

MOLINA DE LINES, María & PIANA DE CUESTAS, Josefina. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo: Representante de una filosofía política española para la dominación de Indias, Escuela de Historia y Geografía, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, University of Costa Rica, 1978. MOTOLINÍA, Toríbio de Paredes. Memoriales o Historia de los indios de la Nueva España. Madrid: Historia 16, 1985, 331 p. MYERS, Kathleen A. “History, Truth and Dialogue: Fernández de Oviedo’s

Historia general y natural de las Indias (Bk XXXIII, Ch LIV)”. Hispania, 1990,

nº 73, pp. 616-625.

O’GORMAN, Edmundo. “Sobre la Naturaleza Bestial del Indio Americano”. Filosofía

y Letras, 1941, nº 2, Mexico: Imprenta Universitaria, U.N.A.M, pp. 141-159;

305-315.

OTTE, Enrique. “Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, alcaide”, in Francisco de Solano & Fermín del Pino (eds.), América y la España del siglo XVI, Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, C.S.I.C, 1982. PAGDEN, Anthony. La caída del hombre natural. El indio americano y

los orígenes de la etnología comparativa. Madrid: Alianza Editorial

América, [1982] 1988, p. 297.

PÉREZ DE TUDELA BUESO, Juan. “Rasgos del semblante espiritual de Gonzalo

Fernández de Oviedo: la hidalguía caballeresca ante el Nuevo

Mundo”. Revista de Indias, 1957, n° 70, Madrid.

PIZARRO, Pedro. Relación del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú. Edited by Guillermo Lohmann Villena and Pierre Duviols, Lima-Peru: Pontificia Católica Universidad del Perú, Fondo Editorial, [1571] 1978, 277 p. RABASA, José. “The Representation of Violence in the Soto Narratives”, in Patricia Galloway (eds.), The Hernando de Soto Expedition. History, Historiography, and “Discovery” in the Southeast. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. RAMOS PÉREZ, Demetrio. “Las ideas de Fernández de Oviedo sobre la técnica de colonización en América”. Cuadernos hispanoamericanos, 1957, n° 95, pp. 279-289. RODRÍGUEZ, Lígia. El discurso moral en la “Historia General” de Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo. Doctoral Dissertation, City University of New York, 1990. SAINT AUGUSTINE. The Political Writings, Washington, D.C: Gateway Editions, 1962. SALAS, Alberto M. “Fernández de Oviedo, crítico de la conquista

y de los conquistadores”. Cuadernos Americanos, 1954, Vol. 2, Tomo LXXIV.

SCARRY, Elaine. Body in Pain. The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, 385 p. TAUSSIG, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror

and Healing. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987, 517

p.

TURNER, Daymond. “Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia general y

natural… first American encyclopedia". Journal of Inter-American Studies, 1964,

n° 6, p 267-274.

VAQUERO, María. “Las Antillas en la Historia General de Gonzalo Fernández

de Oviedo”. Revista de Filología Española, 1987, Vol. LXVII,

p.1-18.

|