|

|

Expedition

Expedition | People

|

Log - August-4-2003

by Gerhard Behrens and Robert McCarthy

Previous | Next

We're Here!

Robert McCarthy |

|

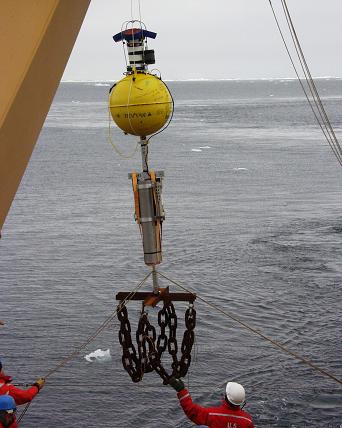

Today we started to place the expensive moorings in the water. The bottom mounted ADCP (Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers) moorings, that were assembled on the back deck in transit from Newfoundland, are ready to start their long two year stay on the ocean floor here at 80 N latitude. In two years, the scientists and crew will return here to trigger the acoustic releases. The big yellow floats will bring the ADCP’s to the surface with the acoustic releases, so they will recover everything except the weights that hold them down. That is VERY important for two reasons, first they have the data on them, which has been recording flow through the Nares Straight for the past two years, and secondly, each mooring costs about $100,000. These instruments will be recovered in the spring, so they are expecting an under-the-ice recovery. So the metal cage around the top of the ADCP will protect the sensors when they hit the underside of the ice. Upon recovery, the scientists will download the data, replace the battery pack, reset the instruments, and re-deploy them for yet another two-year stay in the same location. The sensors and releases are made out of titanium, so they will look brand new. |

| We are now in the narrow section between Greenland and Ellesmere Island known as the Kennedy Channel. Kennedy Channel connects Kane Basin to the south with Hall Basin to the north. The Lincoln sea is just north of Hall Basin, and the science crew would love to get there to place a few more pressure sensors if ice and time permit. The ice conditions that allowed us to get this far north was a big question, but again we have been lucky. We have hit and broken through some pretty impressive sea ice, and this ship continues to amaze me. We are privileged to stand right at the bow, and look straight down as the ship momentarily slides up onto the ice a few feet, before the shear weight of the ship breaks through the ice. VERY COOL, and loud. The strength of sea ice is highly variable. As the salinity of the ice goes down (over time, the salt content seeps out), the strength of the ice goes up. This is because salt is an impurity in the crystalline structure, thereby weakening it. So old ice is stronger than new ice. Also, as the temperature goes down, the strength of the ice goes up. The strength is also a function of how fast it forms. The faster it forms, the more salt is entrained in the ice, so the weaker the ice is. Even though the strength of the ice is variable, the ship can break through 4.5 feet of ice while cruising at 3 knots, which is about 3.5 miles per hour. That’s a lot of power! The ship can supply 30,000 horsepower. I didn’t work it out, but I’m impressed. Tomorrow I’ll talk about the moorings again, and what the scientists hope to discover. |

|

|

|

Yup, it is cold out there.

Gerhard Behrens |

| We’ve been at sea for two weeks. Every day is still an adventure no matter who you are on this ship. For the science crew, a team is putting in the ADCP moorings. For others, the adventure for the day is cutting through lots of thick ice. And no matter who you are, it is pretty cold out there for August 4th , uh…summertime at 80°N lattitude. |

The mooring is ready to go into the ocean. From the bottom up there is: steel bars and chains for the weights; the long tubes are batteries, the release tool, and a salt/temperature device; the big yellow ball is the float; the top is the ADCP device with a peeps. |

|

A mooring is a piece of science equipment that goes into the water and stays in the water. It is attached to a heavy weight to keep it in place. A float is always part of a mooring so that when the scientists want the piece of equipment back, it will float to the top. There is a special tool that allows the float to let go of the weight. The mooring has a peeps, which is an electronic tool that helps the scientists find the mooring. Finally, there is a battery, which keeps everything running. |

| Today’s mooring is called an ADCP because the letters stand for Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler. Here is what it does. Using sound waves that travel through the water, it can measure three things in this part of the ocean: the speed of the water at any depth, which is called the current; the movement of the ice on top; and the thickness of the ice. The mooring also measures the salt and temperature of the water because salt and temperature are important parts of the water’s fingerprint. The scientists will get this mooring out of the ocean next March by melting a hole in the ice. |

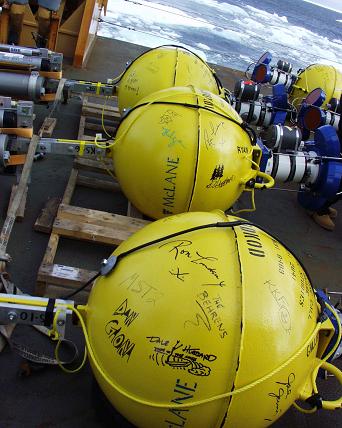

Science and USCG crew sign the floats. |

Some long stretches of sea ice. |

By studying the currents, and especially the changes in currents in a place like the Kennedy Channel, physical oceanographers can learn more about the way water is moving in the Arctic and around the world. |

| We are on a ship called an icebreaker, and that is what we’ve been doing for part of the day. Many people on the ship had an ice alarm this morning. As the hull cut through ice, the grinding, cracking, and crunching sound echoed through the ship and woke everyone. Throughout the day, the ship has been plowing through big patches of sea ice. |

The bow cracks the ice... sometimes. |

Huge chunks float down the side of the ship. |

When the ship cannot cut through the ice, it climbs up on the ice. In a manner of seconds, the weight of the ship breaks through, and the ship can move forward again. |

| It is especially fun to be at the bow of the ship to see the hull collide with tons and tons of ice, break it into huge chunks, and toss it aside. We marvel at the power of the ship, but we are also amazed at the strength and beauty of the ice. |

The pilot tries to steer in a lead, which is an opening in the ice. |

We still see icebergs (we cannot cut through those!). |

Oh, I did say it was cold. The temperature has been between 0 and -8 ° C (32 and 18° F). The wind is blowing at 20 knots (about 23 mph). Everyone is wearing lots of layers. It feels and looks like the Arctic today! |

|