|

|

Expedition

Expedition | People

|

Log - August-3-2003

by Gerhard Behrens and Robert McCarthy

Previous | Next

Heroes "Down-Under"!

Robert McCarthy |

|

Heroes! Everybody needs heroes. People you admire for their courage, will, desire, character, athletic ability, artistic creativity, musical performance, etc. that you strive to mimic. Well, yesterday I was honored to witness 6 heroes! The six individuals are: LTJG Neil Amaral (front row third from left), MST3 Suzanne Scriven (front row to Neilís left), BM1 Dave Grob (back row behind Suzanne), BM2 Darrel Bresnahan (back row first from left), BM3 Scott Lussier (front row on Neilís right), and DC2 Todd Gillick (back row on Daveís right). (See picture 1. Also pictured are MK2 Rich Titus, front row first on left, and BM1 Pat Morkis, back row next to Darrell. Pictures today are courtesy of Dave Forcucci.) These 6 heroes are the ďdiving teamĒ! Yesterday, when they left the ship at noon, nobody thought that they wouldnít return until after midnight. And what makes these divers heroes is not just the physical endurance and mental fatigue that they endured, but their attitude while out there in that tiny boat and when they returned to the ship. They werenít whining to come back to the ship, complaining about how cold they must have been, or how hungry they must have been. They wanted to perform for the science crew, and that meant diving for clams. And even though the thought of diving in these waters might seem glamorous at first, jumping in and going down in these waters took guts. |

| After surveying the area with an underwater camera, they decided to start the dive expedition nearest the coast. The first two divers in the water were Suzanne and Scott. This first dive was the shallowest, and Neil told me they were down about 16 feet deep. At that depth, their visibility was about 15 feet. They dove into kelp beds, and persevered for 34 minutes looking for clams. The next divers in were Dave and Darrell. They went deeper and stayed in about 44 minutes. This dive produced a clam, and everybody was excited, especially Robie and Marry. Then it was Neilís turn, and he dove alone. However, he was ďtendedĒ with a rope and there was a diver suited up on standby if anything went wrong. The two scientists, Robie and Marry, then returned to the ship and all divers had the option to return with them. But they all wanted to go to the next dive site. Here they anchored a pressure sensor to the bottom. Scott went down again, accompanied with Todd. Here the depth was 73 feet, and after the sensor was secured to the bottom, they returned in 17 minutes. They saw clams at this site, but because of the location of site, it was determined not to be the best site for the clams to ďtell their storyĒ. |

|

|

These divers were ready to do it again today, but the ice cover was too thick to allow the small boat into the desired location to place another pressure sensor. These pressure sensors will help the physical oceanographers determine the major driving forces for the flow through Nares Straight. As Dr. Andreas Muenchow said earlier on this cruise, ďitís all about F=maĒ. With the velocity measurements, physical oceanographers can determine the acceleration, and by knowing that, they can figure out what is causing the water to move inside the straight. Ideally they are hoping for at least 4 bottom mounted pressure sensors along the straight, (at least 2 on each side). |

| And while Iím honoring these divers, itís time again to thank the entire crew for their service, and the science crew for their patience. Everyone is working long hours and getting irregular night-sleeps, and they still are more than happy to answer Gerhardís and my questions. Itís a friendly science crew, because I sense that everyone feels blessed to be apart of this team and witness majestic sights we see daily. Thanks again to Drs. Falkner and Muenchow for allowing Gerhard and myself to experience this oceanographic cruise. |

A three ring circus

Gerhard Behrens |

| Itís Sunday, but as I wrote last week, it is a regular workday for the scientists and much of the Healy Crew. The past 24 hours has been a four-ring circus of activity. |

Loading the small boat with drysuits, tanks, extra clothes, underwater camera, and tools for collecting the clams. |

Lowering the small boat, Healy 3, into the water. |

The Rosette Crew took more water samples through the night hours. But remember, there is no darkness, so it was light as they worked from before midnight to about 10 am.

The helicopters took off on another flight to check ice conditions further north.

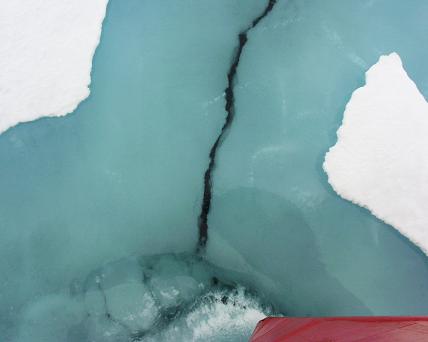

Our ship started breaking through sheets of sea ice this morning. It is hard to describe the feeling of being at the bow of the ship, and watch it plow through big hunks of ice. Even more amazing is the crunching and grinding sound that goes through the ship as we pass over the ice.

Yesterday, a team of science and Coast Guard people began small boat trips to collect clams and to place shallow water pressure moorings. More of those trips were planned for today, but they were cancelled due to the ice. |

| I hope you remember that the clam study is like doing a study of tree rings. In the labs of Oregon State University, the shells will be studied very carefully for the clues they hold. |

Healy 3 heads for the shoreline of Greenland. |

Ice ahead in Alexandra Fiord. |

I also hope you remember that all water has a signature or fingerprint. The water that a clam uses to build a shell leaves its fingerprint in the clamís shell. By studying the clamshells, scientists can figure out the patterns of water run-off from rivers or glaciers. That information can give clues to the weather patterns of the past 10, 20 or even 30 years. |

| The clamshells will also be tested for the metals barium and cadmium. The amount of barium can tell the scientists if the fresh water is coming from the Mackenzie River area of Northern Canada. The amount of cadmium is a clue to the amount of phosphorous, which is a clue to the amount of plants and animals in the area, which is a clue to the amount of ocean mixing that has happened. Thatís a lot of scientific detective work! |

The ice is beautiful, but tough on the hull of a ship! Too tough for the small boat to go out today. |

Breaking the ice draws a crowd in the bow. |

Itís also hard work just getting those clams. It takes a crew of about 10 to get the boat into the water. It takes a crew of three to run the small boat. It takes a team of 6 divers, all taking turns, to dive into the 37-degree water and find the clams, which bury themselves in mud. It takes a few scientists to help find the right place to dive and help the divers record where the clams were taken. |

| Just like the water samples we take, the end result is the scientists believe this information will help them know more about how water is flowing in the Arctic and through Baffin Bay. |

The bow cracks the ice as we steam through. |

We leave a path of broken ice behind us. |

|