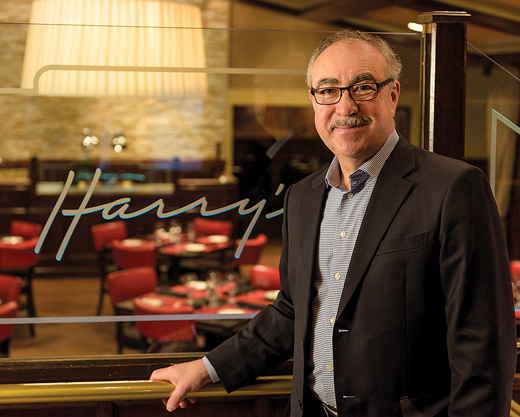

Xavier Teixido, ANR75

Success with a side of compassion

ALUMNI & FRIENDS | When Xavier Teixido, ANR75, looks back on what he’s done as a successful restaurateur, he sees it all beginning with cherished moments in his childhood home.

He remembers his immigrant parents happily melding the cuisine of their native Paraguay with the farm-fresh foods of their new homeland of Delaware. He recalls childhood friends marveling with wide-eyed astonishment that the Teixido family grew snails—“monsters,” as they exclaimed to their incredulous parents—and ate them for dinner.

But more than the dishes themselves, he remembers the music, the culture, the conversations of fellow expats who would become his family, not by blood, but by the common bond of being strangers in an unfamiliar land. There was always room at the table for one more.

“If there was anything that prepared me for this industry, it was seeing how unselfish my parents were,” says Teixido, whose 42-year career has taken him across the country to work at some of the most innovative and extraordinary restaurants in America, then back to Delaware to open premier fine-dining establishments of his own—including the North Wilmington landmark Harry’s Savoy Grill.

The unofficial mantra in the Teixido house was “family and education first.” To that end, his parents were thrilled to see him enroll at the University of Delaware, and less so when he flunked some classes, moved out of the residence halls, and told them he’d happily pay for his own education.

On his quest for financial independence, he landed a job at an upscale restaurant, while working simultaneously on his associate’s degree. Three years later, degree in hand, he moved on to another fine-dining establishment, cooking under a German chef and working six doubles a week. The owner had promised to fund Teixido’s culinary school tuition if he lasted a year, but ultimately reneged.

It was a tough and bitter blow, but steeped in discipline, principled in the Old World European foundation, and profoundly interested in food, Teixido drove up to Philadelphia and parked his Volkswagen Beetle right in front of The Frog, a landmark eatery in the 70s. “I’ll wash your dishes, prep the food, anything you need ,” he told the manager. “I want to be where I can learn and contribute, and I don’t care where I start.”

Teixido was on the job less than a month when he noticed someone walk up to the broiler and help to prepare orders. “You can’t send that plate out looking like that,” Teixido admonished the stranger. “Redo this lamb. Recook those potatoes. I’m going to need you to be more disciplined if you’re working the line.”

The man left, and the kitchen fell to an eerie, almost deathly silence.

“What just happened?” Teixido asked, as a colleague quietly explained that he had just berated The Frog’s famed owner, Steve Poses.

Called into the manager’s office the next day, Teixido faced Poses—who proceeded to name him sous chef. He would later assume that role for the expanded and esteemed Frog Commissary, catering “all of the best houses on the Main Line,” and managing receptions for a who’s who of clients, from Jacqueline Onassis to Luciano Pavarotti.

Dining in America during this period was a unique phenomenon, as American restaurants were trying to find their identity. The only city that seemed to have strong footing in a regional, indigenous cuisine was New Orleans, and there was perhaps no restaurant as prominent as Ella Brennan’s Commander’s Palace.

By 1981, Teixido was sitting across from Brennan as the newest member of her team. His instructions were simple: “Make customers.” Which he did—so successfully that when Brennan suggested he take on the role of executive chef, he chose to continue in management. He’d be part of the team to hire a relatively unknown chef named Emeril Lagasse and would remain at Commander’s Palace for a few more years, before returning to Delaware in the mid-1980s and revolutionizing the dining scene.

He helped open Wilmington’s Kid Shelleen’s as a minority partner in 1984, and then Harry’s Savoy Grill, again as a minority partner, in 1988, becoming sole owner in 1993. He would add a ballroom in 1998 and expand his operations to include Harry’s Seafood Grill on the Wilmington Riverfront in 2003.

“We’ve always tried to reflect the national dining scene,” Teixido says of his restaurants’ success. “We’ve always been hospitality-driven, educating ourselves and our staff to focus on the guests.”

A member of UD’s Department of Hospitality Leadership Advisory Board, Teixido often returns to his alma mater and is consistently impressed with today’s students.

“The students all have industry experience by the time they leave. They’re well dressed, they ask good questions. There’s a great diversity to the student body and a commitment to community service,” he says.

In fact, Teixido credits the late Paul Wise, who founded UD’s hospitality program, with the “tireless and selfless vision” to connect students to the best opportunities in the industry. It’s one he seeks to continue today, through the Harry’s Savoy Grill Hospitality Scholarship, as well as many other initiatives statewide.

Nationally, he has served as chair of the National Restaurant Association and board chair for the association’s Educational Foundation, most recently receiving its 2017 Ambassador of Hospitality Award . Locally, he has raised over $1 million for childhood hunger.

Just as it was for his parents, Teixido sees the intrinsic connection between hospitality, education and community. As he tells current students, “This is a large, competitive industry, but there’s tremendous opportunity to those of you willing to do the work and take care of other people.”