BLACK VOICES ARISE FROM THE PAST

OUR FACULTY | For more than a century, their voices have been all but silent.

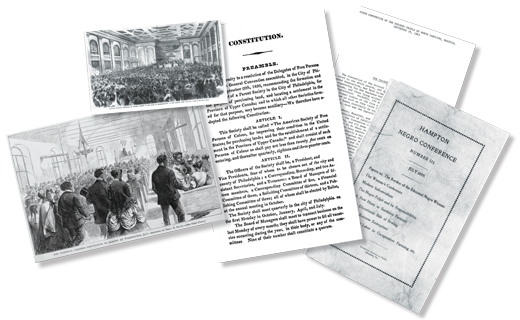

Through the long decades of racial struggle in America, the words and records of early black activists who demanded justice throughout the 19th century have been largely unknown, found only in the pages of old and scattered newspapers and forgotten pamphlets and proceedings.

Prof. P. Gabrielle Foreman believes we all need to hear those words again—and get to know the people who spoke and wrote them. Her work ensures that the injustices they fought, and the solutions they sought, help those of us living today comprehend what black Americans faced and achieved then—and what we face as a nation still struggling with that legacy.

So for four years now, she, along with co-founders Jim Casey, AS12M, and Sarah Patterson, AS12M, and a team of graduate student leaders, undergraduate researchers, community volunteers and faculty from across the country, have been poring over newspaper archives from a long-forgotten era to find glimpses of what really happened inside the “Colored Conventions”—the 60-year series of political meetings from 1830 through the1890s that brought together tens of thousands of black activists intent on making the ideal of democracy and freedom broad enough to embrace all Americans.

At the University of Delaware, the Colored Conventions Project is building an online repository of early black activism. Through the ColoredConventions.org website, scholars, students and interested parties from all walks of life can explore interactive exhibits, zoom in on maps that locate where delegates lived, where they stayed, and how they travelled to conventions. Visitors can peruse photographs of the churches, meeting houses and black-owned boarding houses where they gathered together. These exhibits sit alongside the documents of the conventions, brimming with the speeches and biographies of delegates.

It was a movement suffused with an energy that persisted long after the conventions ended, eventually morphing into such Civil Rights groups as the National Association of Colored Women and today’s NAACP.

“Conventions both document and protest the very state violence—and state apathy in the face of white violence—against black communities that is the subject of protests today,” says Foreman, the Ned B. Allen Professor of English and professor of history and black American studies.

The NAACP also protested such violence, compiling reports and statistics just as the convention’s “committees on murders and outrages” had.

“Black people continue to organize today, much as they did decades and centuries ago,” adds Foreman. “Our research shows that loss, mourning and mistreatment—accompanied by protest—is nothing new for black Americans who, for almost 400 years, have been forced to contend with the denial of the very same rights and protections white Americans routinely enjoy.”

A LEGACY FOR THE FUTURE

There was a time not long ago when just four volumes existed with a sole focus on the Colored Conventions. They were rare, expensive or out of print and shy on the details needed to capture the deep impact of the meetings or tell the compelling stories of their participants.

That would all begin to change in 2012, when Foreman and her graduate class unwittingly launched the entire project with a digital assignment to research the lives of the 1859 New England Colored Convention delegates.

Soon after, they realized that a vast, untapped reservoir of archival materials awaited discovery. Led by Foreman, graduate students Casey and Patterson, and librarian Carol Rudisell, the UD team used crucial grant funding to uncover an ever-growing list of meetings and several hundreds of conventions.

Then professors from across the country began to join the project. More than 1,300 students from universities and colleges from Alabama to California helped track down documents, research the lives of the convention attendees, and study the women who fought for civil rights, but whose names rarely appear in the minutes themselves. Today, UD serves as the hub for dozens of the Colored Conventions Project’s national teaching partners.

“We are building these resources together so that, long after we’re all gone, students and historians will know what early black activists said and did 130, 140 or 150 years ago,” says Casey.

Along with thousands of people whose names have been forgotten, the project has served to demonstrate a far deeper involvement by such luminary black leaders as Frederick Douglass, who attended conventions for at least 40 years, speaking to the crowds in the dignified cadences of 19th-century English — resolutely forceful, yet lyrically poignant:

“Why are we here?” he asked the crowd at an 1883 national convention in Louisville, Kentucky. “To this we answer, first, because there is a power in numbers and in union; because the many are more than the few, because the voice of a whole people, oppressed by a common injustice, is far more likely to command attention and exert an influence on the public mind than the voice of single individuals and isolated organizations.”

At the core of Douglass’ words lies a prime revelation of the project—that the conventions’ energy was sustained by a vast, interconnected and mutually supportive network of activists, and a formidable effort to publish and distribute “meeting minutes” to the general public through black newspapers. So far, the project has identified more than 4,500 participants who attended more than 200 conventions, evidence of their deep and pervasive role in the black community.

THE ELUSIVE DREAM OF TRUE CHANGE

Inside the conventions themselves, black Americans’ quest for equality was defined by repeated calls for rights that other Americans took for granted: equal education, freedom of travel, legal equality, fair labor laws and voting rights. Their methods sometimes drew upon a sense that they could successfully change the system from within, through political means and public opinion. They also held grassroots fundraising drives for communities and schools. Eventually, delegates began newspapers, and sometimes universities, called for in the conventions themselves. And if their fights for civil rights and racial justice met with success too infrequently, they kept the movement alight through persistence amid great odds.

For those involved in the project, this peek into the past has ultimately revealed a new vision of the politically sophisticated movement of the Colored Conventions, a reminder that it continues to this day, with subtly different dynamics, but many of the same dilemmas.

“It challenged my conventional understanding of the narrative of this country,” says Eric Brown, ANR17, AS17, who now works for the Equal Justice Initiative. “It caused me to step back and think about my place as a citizen, and ask what can I do to change things, what can I do to help, what can I do to not be complacent.”