Ripple Effect

The art of attracting and keeping extraordinary faculty

There’s a sign near the door of an otherwise unremarkable office in Colburn Lab—a sign just prominent enough to give proper notice, but inconspicuous enough to be practically invisible to the people who pass each day.

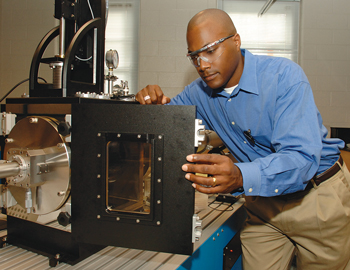

“Thomas H. Epps, III,” it reads. “Thomas and Kipp Gutshall Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering.”

Some might pause and puzzle at the drawn-out title that UD’s “endowed professors” typically get. Others might dismiss it as just another piece of honorary fluffery in a world drenched in promotional noise. But to Epps and to the dozens of graduate students he has taught and nurtured and sent on to great new opportunities, the title represents far more than its nine words could hope to convey.

Epps and other UD professors whose research is supported by benefactors say the impact of financial gifts reaches far beyond the labs and research groups of UD, rippling like a wave to foster the aspirations and even the careers of dozens upon dozens of students—and ultimately bolstering the prestige of entire departments and the University itself.

Talk to Epps about what it has meant to be an endowed professor, or “endowed chair” as they are sometimes called, and he will use words like “freedom” and “flexibility.” For him, it’s not about personal honor or professional status as much as it’s about potential—of both his students and his ideas.

Talk to his students, and they will point to the high-risk, high-reward research the endowment has allowed, the paths toward innovation it has cleared—and the many doors that it could open for them, long after they have left the University.

For Julie Albert, EG11PhD, working with Epps and his group of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers has led not only to significant advances in the complex and infinitesimal world of polymer science, it has helped bring her to a job as professor of chemical engineering at Tulane University, with a research group and endowment of her own.

For Sarah Hann, EG12, it has meant an opportunity to go on to innovative Ph.D. work at the University of Pennsylvania. “It was helpful to have a well-known and respected name tied to my application,” she says. “Just being able to say I came from his lab was a benefit to me.”

Look at the resumes of dozens of other students who have been part of Epps’ research, and the sense of advancement and opportunity becomes clear: assistant professor at Arizona State University. Ph.D. student at Cal-Tech, postdoctoral researcher at Dow Chemical, scientist at Hexcel.

“My experience with him wasn’t just limited to those five years of graduate school,” says Albert, who is researching designer polymers that could one day be used in more practical diagnostic instruments and cleaner sources of energy. “It’s definitely something that comes up every day in things that I’m doing, having worked with him and trained with him.”

Many came to UD because of Epps’ reputation of working at the cutting edge and would also soon discover that being a student of a named professor carried extraordinary benefits. Epps’ graduate students—and even undergrads—are being asked to present at big academic conferences, an honor that frequently leads to networking opportunities, name-recognition and even bigger opportunities.

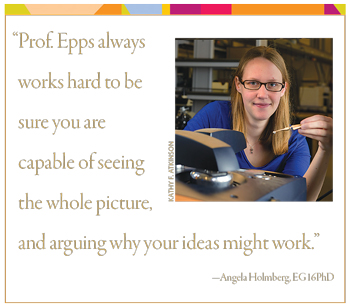

“The networking is the good part,” says Angela Holmberg, EG16PhD. “You need people for jobs, you need people for feedback, to read your research and see if you’re doing something wrong. It gives you encouragement that you’re doing something right.”

For Holmberg, more carry-on effects of working with an endowed professor would become apparent: At a conference in November, Epps introduced her to another up-and-coming research professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—currently the top-ranked school for chemical engineering in the nation. The professor, Bradley Olsen, asked to meet again later, and that in turn would lead to her next adventure: a post-doctoral research job with MIT’s Olsen Group. There, Holmberg will explore ways to recycle waste-stream items—old automobile tires, for example—into new products. “Recycling has always appealed to me,” she says. “I hate seeing litter. I hate throwing things away that still have potential use. I want to work on something that I can feel passionately about for as long as possible.”

Expanding opportunities

Even before they leave UD, students say, endowments bring the prominence and name-recognition needed to access broader opportunities in their fields of study.

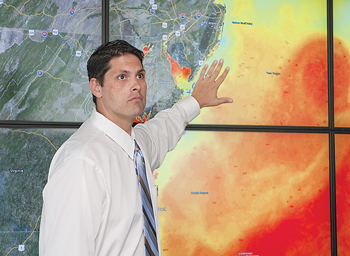

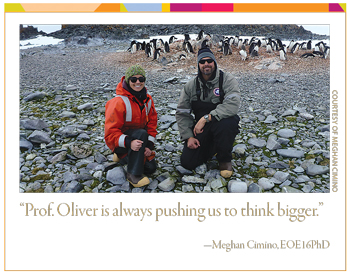

Consider the students studying under Matt Oliver, the Patricia and Charles Robertson Professor of Marine Science and Policy: Of his four doctoral students, three are already lined up to speak at the nation’s pre-eminent ocean sciences conference this year. “Which is astonishing,” says their professor. “I didn’t even get asked to speak—but my students did.”

And the oceanography students are already becoming familiar with a certain sort of fame. In the months since Oliver received his professorship, Megan Cimino, EOE16PhD, has seen her team’s research of Adélie penguins featured in the national media—research that was made possible in part by the Robertsons’ funding of high-tech submersible vehicles based at the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment’s Lewes, Delaware campus. And the work Danielle Haulsee, EOE16PhD, has done with the sand tiger sharks of the Delaware Bay has also attracted the media spotlight—a glare that’s not always entirely welcome to a busy doctoral student, but which surely brings its public relations benefits.

“They’re all over the media,” says Oliver. “And all of them that have been touched by the Robertsons’ endowment have been invited to give talks at huge conferences, at universities.”

An impact beyond numbers

In practical terms, endowments do serve to help fund the nuts and bolts of research: travel, expenses, equipment, even salary. But in Oliver’s view, its biggest promise lies in its potential for creating students with the drive and vision to seek meaningful impact on the world, years after they leave UD. “That’s how I think I can make the world a better place,” he says. “You are far more likely to impact the world through a person than a theory.”

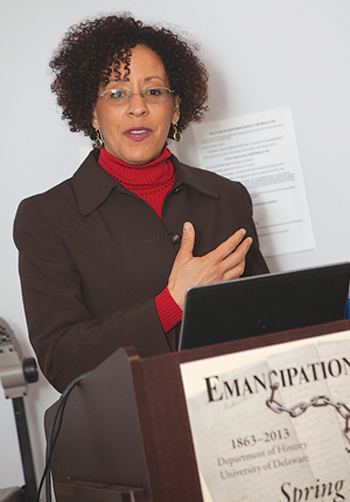

Gabrielle Foreman, the Ned B. Allen Professor of English, with joint appointments in history and Black American studies, also sees the reach scholarship can extend to hundreds of students, at UD and beyond.

Her Colored Conventions project—which digitizes the social networks of African-American political organizers from the 19th century—involves 100-plus undergraduates from the University and more than 700 transcribers from across the country, all working toward a common goal: to educate.

“The student response has been overwhelming, but I’m not surprised,” she says, “We are documenting political struggle and change, crucial to anyone’s sense of self and history.”

It’s clear to Foreman and her fellow professors that even in the sometimes insular world of research—a world that can seem irrelevant to outsiders’ lives—endowments increase the chances of big breakthroughs that can have a broader impact on society itself. In case after case across campus, endowments are allowing scholars to explore game-changing ideas that might have been deemed too risky to explore without the supplemental finances, professors say.

“The funds made available through endowed professorships make it possible to seed a new research project that may not be able to attract funding any other way,” said Babatunde Ogunnaike, dean of the College of Engineering and the William L. Friend Chair of Chemical Engineering.

For Epps, that means being able to pursue his goal of using the waste products of manufacturing to create next-generation plastics that are biodegradable—and thus possibly pave the way toward cups, automobile tires and other disposable products that are less environmentally harmful. For Oliver, it means gaining a greater understanding of how changes in environmental conditions—many of them man-made—may be impacting sea life. For Foreman, it’s about understanding the deep and unstudied voices and social networks of a century past.

The power of philanthropy

The University of Delaware has 113 endowed professorships, with a goal of establishing 50 more by 2020. Next to competitor institutions, this number is low.

But it’s growing. In the past few years, UD has received gifts and commitments to establish 18 professorships, five of which were made in the past year alone.

“The donors who make these gifts either really understand academia and the need for professorships, or they think of the impact UD professors have had on their own careers and want to continue that tradition,” says Monica Taylor Lotty, vice president of Development and Alumni Relations.

Like William Severns Jr., EG50, who studied under Allan Colburn, Robert Pigford, Jack Gerster and other “outstanding engineers, brilliant minds” of chemical engineering. “Right here in Delaware, I was exposed to top faculty from all over,” he says. “I admired that.”

To continue—and ensure—this tradition of faculty excellence, he and his wife, Jacqueline, recently committed $4 million to establish the William Severns Jr.Distinguished Chair of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

They are not alone in their generosity.

“The strength of our faculty is absolutely necessary for the quality of the program to continue,” says Alan Ferguson, EG65, a UD-trained engineer and venture capitalist who, with his wife, last year established the Allan and Myra Ferguson Distinguished Chair of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. “Chemical engineering is a star at UD, and we want to keep it that way.”

In many cases, donors establish faculty endowments to support an area of research they view as a priority, a way to create lasting and meaningful change in the world beyond anything they themselves could orchestrate alone.

“We focus our giving on education, the sciences and technology because those are the causes we believe in. UD researchers are really digging into what’s going on under the ocean using the latest technology. So it’s satisfying for us to support an entire project—the personnel, the hardware, everything—and see it prosper,” says donor Charles Robertson.

By maintaining a close relationship with benefactor Tom Gutshall, EG60—a widely respected entrepreneur and still a driving force in next-generation medical testing devices—Epps says he and his students have gained crucial access to the world where ideas and innovations are transformed into products and solutions. (Read about Gutshall’s impact).

For the University itself, those kinds of developments can certainly lead to profit through patents and even the heightened academic status that can attract more top professors and students.

Talent magnets

More and more, faculty endowments are being seen as an essential tool in an increasingly challenging task faced by university administrators—getting great professors to come to UD, and keeping great professors from going somewhere else.

As College of Arts and Sciences Dean George Watson, AS85PhD, explains, “Professorships are like a university’s equivalent of a Nobel.” (It’s worth noting that UD’s own Nobel laureate, the late Richard Heck, was the Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus of Chemistry.)

And it’s tougher—and more critical—than ever to win that fight for top professors, especially when competing with relatively richer universities, administrators say. Rivals are constantly on the doorstep, trying to woo away the best and brightest. And deans are constantly alert for signs that a professor might be hired away, so that countermoves can be made before it’s too late.

“We do that proactively,” says Provost Domenico Grasso, the University’s chief academic officer. “We’re not waiting for the offer letter to come in from MIT. It’s something we are ever-vigilant about.”

Endowments are becoming essential tools in this ongoing struggle, especially for research universities like UD that are trying to beef up faculty and infuse high-priority programs with academic strength. It’s also important in cases where the University is trying to add momentum to growing efforts, such as the new initiative to make UD a hotspot for training tomorrow’s cybersecurity experts.

“We want people of named-professor caliber leading our big initiatives,” Grasso says.

Once a professorship is funded and put in place, the benefits tend to be sustained and self-perpetuating, administrators say. With great professors come great students—and then possibly more great professors. As the saying goes, “talent goes where talent is.”

But in the end, the ultimate goal—and the ultimate worth—of the endowments is not the University’s status or the professor’s ego, but the students’ momentum in the years that lie ahead, and how positively the world is affected by that energy, insiders agree.

‘’I feel like I was better prepared to start up my lab at Tulane having seen what it took to start up a lab with [Prof. Epps] in Delaware,” Albert says. “In many ways, he’s still a role model for me when I ask myself, ‘Am I on track for my career?’”