Cold War leaves a chilling legacy

ALUMNI | It was 1998. The Cold War had been over for seven years. Chunks of the Berlin Wall were being traded on something called the Internet. Old Soviet uniforms were considered “in” at all the popular European nightclubs. Whole industries in the former Soviet republics could be had for cold cash.

The nightmares of the Cold War were over. Children in the U.S. no longer practiced civil defense drills by hiding under wooden desks. Few Americans knew where the closest fallout shelters even were.

The superpowers were at peace. Everything was fine.

They were good times for David E. Hoffman, too.

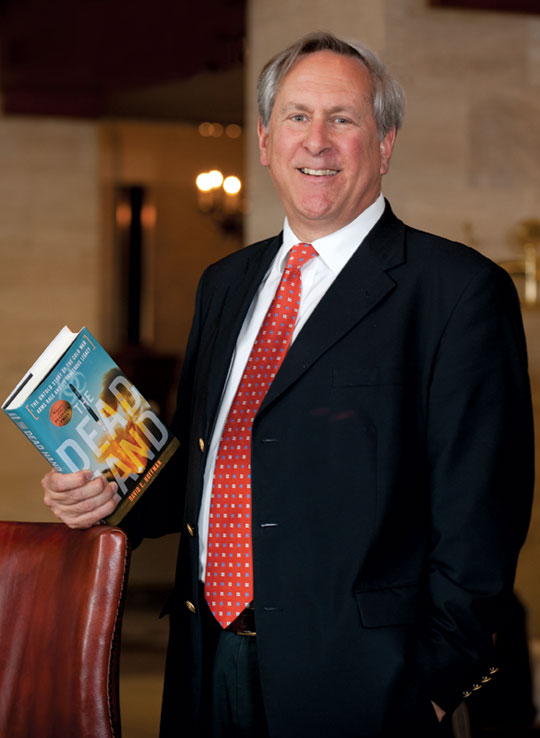

A UD alumnus and old-hand reporter, Hoffman was climbing toward a career apogee. He was Moscow bureau chief for the Washington Post, had recently finished a book on the rise of Russian oligarchs after the fall of the Soviet Union, was being groomed for a management position in Washington and was looking forward to taking his family back home.

And then a man came into the bureau with a simple, yet frightening, statement.

“Something,” he said, “is missing.”

In the days before the fall of the Wall, hundreds of kilos of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium, as well as functional nuclear warheads, were stored throughout the USSR, guarded by a seemingly unlimited supply of well-armed soldiers.

Hoffman’s visitor, drawn by the bureau chief’s “open door” policy, laid a hot potato square in the middle of his desk: Guards. There weren’t any guards anymore, he said. They’d melted away.

As the frenzy of freedom and the promise of democracy spread throughout the land, the Russian economy couldn’t keep up and crashed, and payrolls were not met. And the guards—at first in ones and twos, and then by platoons and then by whole companies—just disappeared into the hinterlands. Melted away, leaving nothing but bunkers full of weapons-grade nuclear material.

The material was enough to make countless bombs for whoever had the cash to buy it.

Hoffman’s visitor, a contractor for the U.S. Department of Energy tasked with accounting for the enriched material as part of a disarmament treaty between the two superpowers, spent months on his mission, and that’s when he realized that something was terribly wrong.

The Cold War may have been over, but the next war could be waged with the unguarded material, and he couldn’t find anybody to listen to him.

Until he found Hoffman.

That was the beginning of Hoffman’s search, one that eventually earned him the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction for his book The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy.

The secrets he wrote about could have determined the future of the world. And to this day, those secrets scare him.

Hoffman attended UD in the early 1970s and went on to make his mark on the world without completing his degree—“although I wish I had,” he says.

He found himself a political science major but ended up trapped by the siren call of journalism. It was the era of Watergate, the Pentagon Papers, student demonstrations. “It was, at that time, a school of real-time political education,” Hoffman says. “It was a time of thinking big.”

He distinctly remembers Prof. Edward Nickerson, former head of the then-nascent journalism program, providing vital support during a series of controversial articles in the student newspaper The Review about the validity of solar power. “I was really impressed with the school and the administration,” says Hoffman, who became the paper’s editor. “They gave The Review a completely free hand.”

And while he won’t admit it, he probably spent more time churning out The Review than he did attending lectures. He was at the University four years, but he can’t tell you how many credits shy of a degree he was. Still, he credits UD for preparing him for what would be a world-ranging successful career.

He met his future wife there, the then Carole Fleming, another political science major. He spent a year working for The Morning News in Wilmington, and then followed the journalism call to Washington, D.C. (Carole Hoffman graduated in 1976 and then earned a law degree.)

Hoffman signed on to the Capitol Hill News Service and in 1982, at age 28, was hired by the Washington Post. He went on to cover the White House, the 1988 George Bush presidential campaign, the Middle East and the State Department before becoming the Moscow bureau chief.

“It was a time of raucous capitalism,” Hoffman says of his time in Moscow, and while the nation was in turmoil, weapons-grade nuclear material “was lying all over the place.”

During his research, using documents never before disclosed, Hoffman also discovered that before the fall of the Soviet empire, the USSR developed a system that would automatically retaliate if the U.S. or other NATO countries launched against them. Designed to run without human oversight, the Soviets then had second thoughts about this “Dead Hand” system and gave control of it to three duty officers in a bunker.

“Those guys are still on duty today,” Hoffman says.

Now back in the U.S. as a Post contributing editor, he says what he learned in Moscow stays on his mind.

“The legacy of the Cold War is not over,” he says. “The weapons of the Evil Empire lived, and they live on.”

Article by Ted Caddell, AS '83