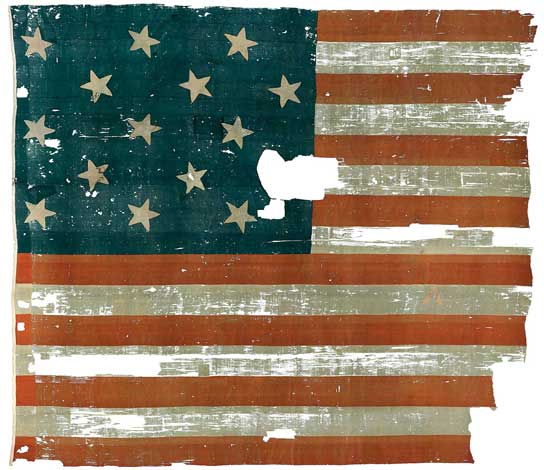

Thanks to conservationist, our flag is still there

uzanne Thomassen-Krauss, AS ’82M, knows its secrets. After examining every square inch of the 30-by-34-foot flag known as the Star-Spangled Banner, she can tell you where a now-invisible signature likely was once scrawled. She knows how many of its 37 patches are from fabric not original to the flag described in America’s national anthem. She has a solid hunch about the origin of a large tear near the stars. And, she thinks she knows its biggest surprise.

Thomassen-Krauss believes it is not the flag whose broad stripes and bright stars waved through the perilous fight.

“What we believe is that the large flag was not flying during the battle. They would have taken it down when the battle started,” she says, explaining her theory that a smaller, storm flag flew over Fort McHenry throughout the Battle of Baltimore in 1814. But, she says, the large flag was hoisted when the shelling stopped, and so it is the one that inspired Francis Scott Key by the dawn’s early light.

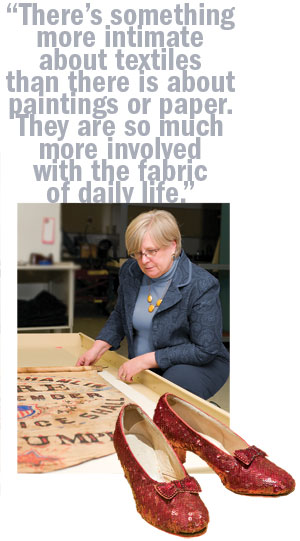

Thomassen-Krauss led the recently completed, 15-year conservation project of the Star-Spangled Banner, in her role as senior textile conservator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. For 20 years now, just about every item brought into the museum that contains even a speck of fabric has been examined and restored under her supervision.

The Star-Spangled Banner, or SSB as she’s fond of calling it, is by far the largest project Thomassen-Krauss has ever undertaken. The museum constructed a new laboratory specifically designed for the flag, where visitors peered at the progress through a 50-foot-long glass wall. Painstaking effort went into inspecting, cataloging and cleaning it, always taking care not to damage the fabric.

For Thomassen-Krauss, it was an opportunity to combine two of her passions—art and science. She says she continues to use skills honed as a student in the renowned Winterthur/University of Delaware art conservation program.

“I got to do a lot more research than you normally get to do when you are working in a museum that has a very active exhibition program,” she says. “I have the luxury of being able to explore.”

And still more exploration awaits. The large tear near the flag’s field of stars particularly interests the textile expert. She theorizes that a shell pierced the flag on the day before the battle began, a shell the British might have fired to test the range of their guns. That, combined with her extensive knowledge of textiles and their uses, forms her opinion that the SSB did not fly during the rainy battle.

“Textiles at that time were extremely expensive,” she says. “The flag cost $405. The house that Mary Pickersgill, the maker of the flag, lived in probably cost, in equivalent dollars, about $1,500.

“It was a huge outlay for the fort, so they took good care of it.” Flying it during a rainstorm would not have been prudent.

“But we know the big one is the one that Key saw because we have two eyewitness accounts,” she says. The journal entries of a British sailor and a young Baltimore boy both discuss seeing the large flag raised at dawn, with the battle over and the British sailing away.

Key began writing the national anthem that morning.

A 1914 conservation project cleaned the flag for the anthem’s centennial. Thomassen-Krauss’ recent conservation treatment removed dirt from the fabric using, among other methods, ordinary cosmetic sponges, carefully blotting the fabric

Thomassen-Krauss says every object acquired by the museum presents a new challenge. Her conservation portfolio showcases a host of items, from Thomas Jefferson’s writing desk and gowns worn by the nation’s first ladies to Dorothy’s Wizard of Oz ruby slippers and Kermit the Frog.

Textiles, she says, offer a special connection to history because they are typically not intended to become historic relics but often are simply ordinary items.

Article by Andrea Boyle, AS '02