What do the current Second Lady of the United States, the organizer of the Philadelphia Flower Show, the president of the Medical Society of Delaware, a world expert on locust control, Jackie Kennedy’s first White House curator, the developer of new refrigerant mixtures to replace ozone-depleting chemicals and an Academy Award winner for visual effects for Titanic all have in common?

They all received graduate degrees from the University of Delaware.

Likewise, UD’s current population of nearly 3,500 graduate students, one-quarter of whom are international students, is destined to make significant contributions to their communities and to the world, Debra Hess Norris says.

“Their impacts will be felt ‘here, there and everywhere,’” Norris notes, quoting a favorite Beatles’ lyric. “As intellectual leaders and scholars representing more than 100 countries, they will address challenges on local to global levels and expand the boundaries of human understanding.”

Norris, AS ’77, ’80M, vice provost for graduate and professional education, chairperson of the Department of Art Conservation and Henry F. du Pont Chair in Fine Arts, is the University’s greatest advocate for the graduate community. She works with administrators and collaborators across campus and beyond to develop robust new interdisciplinary programs and funding opportunities, provide expanded services to assist a growing and more diverse graduate population, showcase graduate achievement to enhance visibility, increase funds for professional development and offer student workshops on topics ranging from research ethics to grant proposal development and dissertation writing.

Graduate programs are targeted for growth and development in the University’s Path to Prominence™, the strategic plan unveiled by President Patrick Harker last year, which seeks to build UD’s strengths across the academic, research and community service spectrum. In addition to expanding the excellence and reach of signature graduate programs in areas ranging from art conservation and public horticulture to chemical engineering, marine science and public policy, increased emphasis will be placed on the development of professional education opportunities in health, education, engineering, business and law.

UD offers 43 different doctoral and 115 different master’s degree programs across its seven colleges and more than 50 research centers. Many are regarded among the best in the nation, such as the Plant and Soil Sciences Program, whose students have received more dissertation awards from the Soil Science Society of America in the past 10 years than any other U.S. institution.

Another is the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, which is one of only five such programs in the country to offer the master’s degree, a leader in educating stewards of the world’s art and cultural treasures.

The graduate program in chemical engineering, the oldest graduate program at UD along with chemistry, is ranked among the top 10 nationally by U.S. News and World Report, and is one of the top producers of Ph.Ds in the United States.

Research centers expand the depth and breadth of UD graduate education, as do busy, University-based clinics. Graduate students in sociology and criminology, for example, have the benefit of working with two internationally renowned research centers at UD, the Center for Drug and Alcohol Studies and the Disaster Research Center, while students in the Biomechanics and Movement Science program gain hands-on experience assisting patients in UD’s Physical Therapy Clinic, and graduate students in psychology help community residents in the Psychological Services Training Center.

Additionally, emerging health science partnerships involving the University of Delaware, Christiana Care Health System, Thomas Jefferson University and Nemours/A.I. du Pont Hospital for Children are providing a wealth of new opportunities for collaborative research on important topics.

Across the campus, graduate students are conducting research on subjects ranging from breast cancer to solar energy, designing landscapes using native plants through a program with world-renowned Longwood Gardens, teaching an introductory course on the oceans to undergraduate students, exploring the history of technology in a cooperative program with Hagley Museum and assisting persons with disabilities.

They can be found around the world, too, traveling by moped through the jungles of Sumatra to document and save endangered languages, plunging to the floor of the Pacific Ocean in a submersible to study how life can thrive in a deep, dark world, documenting 18th-century churches in Brazil and learning international business skills in a joint program with the Grenoble Graduate School of Business at the foot of the French Alps.

As UD’s graduate students go about their work, they contribute significantly to the creation of knowledge and to the University’s research, education and public service missions.

“Our graduate students are deeply committed, engaged and highly skilled, and we look forward to welcoming many more of these energetic scholars to our UD family in the future,” Norris says. “We remain firmly committed to creating an educational community that is intellectually, culturally and socially diverse, and enriched by the contributions and full participation of persons from many different backgrounds.”

Mathematician shares her formula for success

LaShona Burkes has always loved mathematics. It permeates her life, from the student assessment data she analyzes at work to the calculator on her keychain. “In fact, I feel the path to living my life is like a math problem to be solved,” she says.

Burkes excelled in math in school and won a Fulbright Scholarship to attend Hampton University. After receiving her bachelor’s degree, the first-generation college graduate decided to pursue a doctorate at UD.

She says she knew she was interested in mathematics education but not necessarily in being in a classroom every day. Then she met Prof. Ratna Nandakumar in the School of Education, who introduced her to the field of educational measurement. The University offers a specialization in research methodology and evaluation at the doctoral level that is designed to prepare students to develop, critically evaluate and properly use quantitative and qualitative methodologies to advance educational research.

“The University of Delaware gave me a different view of applying mathematics,” Burkes says.

Her dissertation research focuses on identifying the potential sources for differential mathematics achievement among different socioeconomic groups of middle school children.

“My cohort was small and very supportive, as were my adviser and the administration in the School of Education,” Burkes says. “This type of learning environment was so important to me, and it was much appreciated.”

During the second year of her doctoral program, Burkes worked for GEAR UP, under the direction of Prof. Melva Ware, to motivate eighth-graders to take algebra. The federal initiative is designed to increase the number of low-income students who are prepared to enter and succeed in college.

With her doctoral degree now in sight, Burkes is working as a data analyst in the Office of Accountability of the School District of Philadelphia.

In her free time, she is helping to prepare Delaware high school students for the SAT exam. Eventually, she wants to tutor middle- and high-school students in math and teach at a community college.

Going green with hydrogen

Erik Koepf has been concerned with the protection, preservation and conservation of the environment for most of his life, which is precisely why he chose UD for his doctoral studies in mechanical engineering.

Specifically, he was attracted by the National Science Foundation-funded IGERT (Integrative Graduate Education and Research Training) Program in Solar Hydrogen. The program is aimed at developing “energy experts” through the integration of relevant concepts from science, engineering, economics and social sciences.

“I couldn’t have created a better program if I had tailored it myself,” Koepf says. “I am confident that the IGERT program will aid me in minimizing wasted potential in our world.”

His research focuses on the development, design and demonstration of a laboratory-scale unit to generate hydrogen using solar thermochemical technology for fuel cell applications. His advisers are Prof. Ajay Prasad, principal investigator of the University’s fuel cell bus project and director of UD’s Center for Fuel Cell Research, and Suresh Advani, George W. Laird Professor of Mechanical Engineering.

“Erik’s work will contribute to our fuel cell bus program in an important way,” Prasad says. “Producing hydrogen from non-fossil sources is a very desirable objective, and Erik is researching methods to use highly concentrated sunlight to produce hydrogen using a two-step thermochemical cycle based on zinc oxide . . . . If his design is successful, we will install this system on our campus and be able to run our fuel cell buses on ‘green’ hydrogen in the future.”

The son of a commercial fisherman, Koepf studied mechanical and energy engineering at the University of Washington in Seattle and at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Before coming to UD, he worked on various environmental and energy awareness projects.

The multidisciplinary IGERT program has been a perfect fit, Koepf says, allowing him to “bridge the gap in understanding and education about sustainable, renewable energy sources and technologies.”

Geologist gives teens a new view of scientists

Katie Skalak knew the students at Wilmington’s Howard High School didn’t think she looked like a scientist.

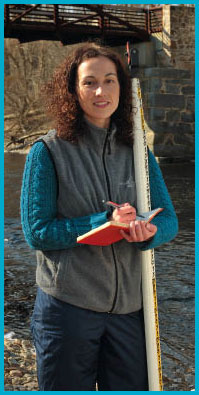

“Seeing images of me in a canoe, walking the river, getting dirty—they didn’t see that as scientific research,” says Skalak, a doctoral candidate in geological science who studies sediment contamination in rivers. “I think they expected a lab coat.”

But that’s one reason she was there, to change the students’ ideas about science. Skalak was part of the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Teaching Fellows Program in K–12 Education. Also known as GK–12, the program paired nine UD graduate students in the science, technology, engineering, and math disciplines with teachers from the New Castle County (Del.) Vocational Technical School District for one year.

The idea behind GK–12 is that the graduate fellows improve their communication and teaching skills, while teachers and students get enhanced instruction.

Skalak calls her involvement with the program life changing and describes being in the classroom as “awesome.”

In 2006, her first year as a fellow, she says the thought of working with high schoolers intimidated her a bit. But it didn’t take long for a connection with the students to take hold. She says she learned how to talk about her work so others outside the scientific community could understand it.

Her first year in the program culminated with a weeklong project for which she drew from her own research studying mercury contamination of a recreational water source. Skalak says the lesson helped her students understand the complexity of the situation, while broadening their view of science.

“I wasn’t born a scientist,” she tells her students. “I became one.”

Helping couples grow stronger in adversity

Amber Belcher, a third-year doctoral student in psychology, is exploring what holds couples together, what keeps marriages strong, in the face of one of life’s most-feared adversities: cancer. With more than 1.4 million new cases of cancer expected to be diagnosed this year in the U.S., it’s not an uncommon adversity.

As part of her doctoral research, Belcher works two days a week as a psychotherapy extern at Christiana Care Health System’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center in Delaware, where she helps patients and their spouses cope with breast cancer.

The University is home to the Center for Translational Cancer Research, a partnership involving Christiana Care Health System, A.I. du Pont Hospital for Children and UD, focusing on cancer research and education. Belcher is in the room as part of the clinical team when a diagnosis of breast cancer is delivered to a patient and the course of treatment is discussed.

“My goal is to help patients and their spouses deal with the fear, anxiety, depression and, in some cases, grief associated with a cancer diagnosis,” Belcher says. “My focus is to talk about their concerns and ultimately to get the marriage strong again, get the couple happy again.”

For couples facing a cancer diagnosis, Belcher points out keys to coping and coming out of the experience stronger: communication, responsiveness and journal writing. “It’s important for couples to realize it’s OK to be afraid and that while the focus is on the patient, the cancer really is a shared experience,” she says. “Being willing to talk about your fears and concerns is important, but you also need to have a partner who is receptive and assuring.”

As part of her doctoral research, Belcher asks couples to keep a journal that examines how they adjust to the cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Belcher was attracted to UD by the work of Profs. Jean-Philippe Laurenceau, now her adviser, and Larry Cohen. Laurenceau conducts social psychology research on couples, while Cohen’s research focuses on stress and coping. UD’s Clinical Science Program is accredited by the American Psychological Association and is a member of the prestigious Academy of Psychological Clinical Science.

Doctoral student lends a hand in biomechanics

When Paulo Barbosa de Freitas Jr. was 15, he left his home in Guará, in the state of São Paulo, to play basketball in another Brazilian city.

But then his teammates began growing taller and he didn’t, so he decided to pursue a different goal—to be the first in his family to earn a degree from a renowned university.

De Freitas earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at São Paulo State University at Rio Claro, studying motor control, how the brain controls the muscles needed for balance, in elderly people.

During that time, he met Slobodan Jaric, now a professor at UD. Inspired by Jaric’s research on hand function in patients with multiple sclerosis, de Freitas won a prestigious Fulbright Scholarship to come to the University to pursue his doctorate in biomechanics and movement science. The novel UD program, ranked among the nation’s best, is advancing the study of the human body in an interdisciplinary way, integrating sports biomechanics, physical therapy, applied physiology, engineering and computer science.

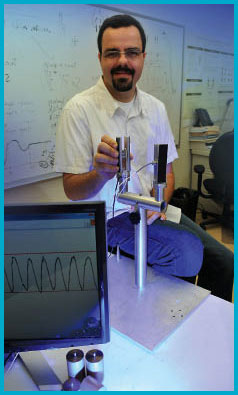

De Freitas has been working with Jaric to develop a diagnostic device that can measure hand function more precisely than ever before and serve as an early detection tool for multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders.

In UD’s Human Performance Lab, de Freitas administers simple tests to healthy subjects and to patients with multiple sclerosis, measuring forces and weight as they grasp and lift a rectangular sensor.

Ultimately, de Freitas wants to build a portable unit that doctor’s offices and clinics can use to test a patient’s motor control before and after rehabilitation or medication. Individuals with Parkinson’s disease and those who have suffered a stroke or have other neurological diseases would all benefit, he says. He’s also interested in applying the technology to patients with diabetes.

Dual degree program means business

Weiping Wang first decided to study biology as an undergraduate because, she says, “the 21st century is known in China as the biology century.”

But after earning her bachelor’s degree at Sun Yat-Sen University in her native country and coming to the United States to enroll in UD’s doctoral program in biology, Wang decided that this is also the century of business.

“I was always focused on science, so I never knew much about the world of business,” Wang says. “I think that happens a lot in companies—the scientists and researchers don’t know much about finance and customer needs, and the business people don’t know much about the science.”

After learning that UD offers a way to combine advanced study in both disciplines, she enrolled in a new dual-degree program and is on track to become the University’s first graduate to simultaneously earn a Ph.D. in biological sciences and a master of business administration (MBA) degree. She has finished her doctoral coursework and now spends her days in the lab, where she conducts research on the process of DNA replication in cells, while preparing to write her thesis. In the evenings, she is busy finishing up her MBA courses.

Wang admits that the workload is “challenging,” but she says the knowledge she’s gaining and the future career benefits she expects are well worth the investment of time. And, she points out, most of her classmates in the MBA program work full time in business during the day. “So they’re busy, too,” she says. “It’s just that my work is in the lab, and theirs is in an office.”

Wang says she thinks that her MBA courses will be helpful whether she works in industry, as she originally planned, or if she decides to remain in academia.

“I’m learning business concepts that will be very useful no matter what I do,” she says.

The making of a leading man

A shoulder injury playing hockey in high school put Matthew Simpson’s hopes for a professional career permanently on ice. But as fate would have it, the injury enabled the Minnesotan to explore another interest—acting. As a 16-year-old, he was cast in Romeo and Juliet, and from that experience, he says, “it was very clear that I wanted to be an actor.”

Last year, at age 21, Simpson became one of the youngest students to be admitted to the University’s nationally renowned Professional Theatre Training Program.

Once every four years, a group of exceptionally talented students is selected for admission to the graduate conservatory, which provides three years of training leading to the Master of Fine Arts degree. Students perform with the University’s Resident Ensemble Players, a professional acting company.

For an actor so young, Simpson had impressive credentials, including leading roles with the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey and Chamber Theatre Productions. A four-month national tour took Simpson to a different city every day.

“It was a lot of fun, but also very grueling,” he says.

So grueling, in fact, that Simpson got sick and lost a lot of weight, which underscored to him how important it is to have a well-trained voice and body, not unlike that of an athlete’s, to be able to perform show after show.

“Some of the key reasons I came to UD were because this program focuses on the classical repertoire and on the very technical training of the voice and body,” he says. “This is the only program in the country where you weight-train three times a week, do Pilates and find out about muscles you didn’t even know you had.”

Typically, fewer than 25 students are admitted to the program every four years, and the faculty/student ratio is one to five.

Simpson describes “an energy at this school that just blows outsiders away,” crediting program director Sanford “Sandy” Robbins. “What he’s done to create this program is unbelievable.”

Genetic research takes aim at poultry disease

Michele Maughan, who enrolled at the University as an undergrad because of an intense interest in animal science, was accepted to veterinary school after graduation. But an undergraduate research project in her senior year led her to follow a different path.

She worked with Profs. Calvin Keeler (now her adviser) and John Dohms in the Department of Animal and Food Sciences to sequence the genome of Mycoplasma synoviae, a microscopic parasite that causes upper respiratory tract infections and tendonitis and bursitis in poultry.

“It was my first exposure to the research side of animal science, and I loved it,” Maughan says. “It really opened my eyes to new horizons.”

Today, after earning an Honors Degree with Distinction, she is a third-year doctoral student, investigating the immune response of different poultry species to avian influenza. “What is so different between a duck and a chicken that the duck is unaffected by avian flu while an infected chicken dies from the virus?” she asks.

In UD’s state-of-the-art Allen Laboratory, Maughan is working to determine what genes are expressed, or turned on, under infection. When infected by the pathogenic H5N1 strain of avian flu, she says, a chicken’s immune system over-responds.

“It’s totally out of control,” she says. “I’m looking at knocking down genes in this immune response to help infected animals have a better outcome clinically.”

In 2006, while finishing her master’s degree at UD, Maughan was awarded the Richard B. Rimler Memorial Paper Scholarship for excellence in poultry research at the annual meeting of the American Veterinary Medical Association held in Honolulu. “It was a total thrill to be there—I was meeting the celebrities of my world,” she says.

Maughan also is taking business classes, tutoring at the Academic Enrichment Center and serving as president of the Graduate Student Senate. “I’m really learning a lot,” she says. “This position allows you to advocate for grad students and build strong relationships across campus and with the community.”

She and her fellow grad students have volunteered for numerous service activities. The student leadership experience has been so positive that Maughan now is considering a career in academic administration.

“I have lots of options open, and they are all good,” she says. “I can’t go wrong!”

To learn more, visit the Graduate & Professional Education Web site,

www.udel.edu/gradoffice.

Article by Tracey Bryant

Writers Elizabeth Boyle, Diane Kukich and Ann Manser contributed to this article.

Photography by Kathy F. Atkinson