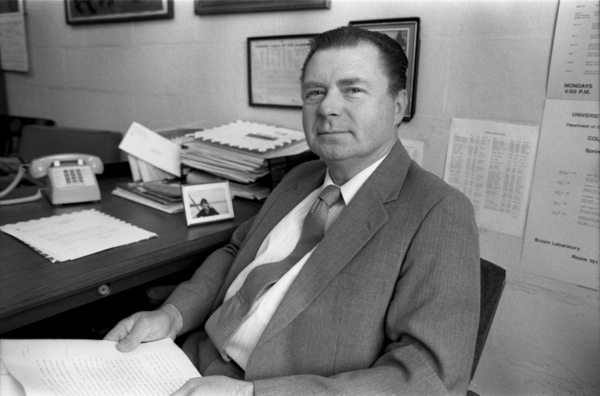

In Memoriam

Richard Heck, professor emeritus and Nobel laureate, dies

Editor's note: To watch a video featuring Prof. Richard Heck and the impact of his work, click here.

12:26 p.m., Oct. 10, 2015--Richard F. Heck, Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at the University of Delaware and a 2010 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, died on Oct. 9 in Manila, where he lived. He was 84.

His pioneering research changed the world in many fields, including pharmaceutical manufacture and discovery, DNA sequencing and electronics.

In 2010, Prof. Heck — and fellow researchers Akira Suzuki of Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, and Ei-Ichi Negishi of Purdue University — received the Nobel Prize “for palladium-catalyzed cross couplings in organic synthesis.” Palladium-catalyzed cross coupling is used in research worldwide, as well as in the commercial production of pharmaceuticals and molecules used in the electronics industry.

“On behalf of the entire University of Delaware community, I extend deepest condolences to Dr. Heck’s family and friends and to his University colleagues and former students,” UD Acting President Nancy M. Targett said. “His groundbreaking work that was saluted by the Nobel Prize Committee demonstrates how scientific inquiry can have a profound effect on the everyday lives of us all. We are honored that Dr. Heck spent 18 years of his distinguished career on our chemistry faculty.”

“The achievements of Dr. Heck stand as a reminder to us all that the ideas and actions of an individual can have a profound effect on the world,” UD Provost Domenico Grasso said. “I know his example has already served as an inspiration for many in our community and that he will continue to inspire our campus and our students for years to come.”

Delaware Gov. Jack Markell called Dr. Heck "a great American whose intellect and curiosity contributed to significant breakthroughs in his field." He said, "I had the opportunity to speak to Prof. Heck after he received the Nobel Prize, and he spoke of how much he enjoyed his time in Delaware.... His family and friends can find comfort in knowing future generations will continue to benefit from the findings of his research, and his memory will live on in the work of those he inspired during his tenure at UD.”

National Science Foundation Director France Cordova said, "“I was deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Richard Heck, a pioneering chemist and Nobel laureate. NSF is proud to have supported Dr. Heck multiple times in his career. Carbon-based chemistry has led to important discoveries that build on its significant role in nature. And Dr. Heck’s research specifically in this field led to innovations now widely used in everything from pharmaceuticals to agriculture. Our heartfelt condolences go out to his family and friends.”

Colleagues remember

John Burmeister, Alumni Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry and associate chairperson of the department, said Heck “personified the sobriquet ‘Walked softly, but carried a big stick.’ He was quiet and unassuming — indeed, somewhat shy. His lecturing/teaching style was straightforward and noncharismatic, and he walked with a slight limp from a childhood disease. However, in the organic research laboratory, he was a giant, a lion, a genius!”

Burmeister noted that his discovery of what became known as the Heck Reaction is “now generally regarded as one of the most useful organic reactions ever discovered. In testimony thereof, about 120,000 references to the Heck Reaction have appeared in the scientific literature since 1980!”

Joe Fox, professor of chemistry and biochemistry, said, “What made the Nobel Prize to Heck especially inspiring to me was Heck himself. He was a modest person who always gave generous credit to others in the field. He was always careful to note the impact of his students, colleagues, and even his own Ph.D. adviser whenever he gave a talk about his work. As a scientist, Prof. Heck devoted himself to chemistry, and made contributions of fundamental and lasting importance. As someone who was truly ahead of the curve, it took time for the scientific community to fully appreciate the significance of his work. Witnessing the ultimate recognition of Heck’s work with a Nobel Prize was absolutely remarkable.”

Mary Watson, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, said, “I am very sad to learn of [Prof. Heck’s] death and am thankful that I had the opportunity to meet him. It is difficult for me to express the deep respect and awe I have for Prof. Heck’s work as well as his character.

“The importance of Professor Heck's scientific contributions cannot be overstated,” she said. “His discovery that palladium catalyzes the formation of bonds between carbon atoms revolutionized the way that chemists make molecules. His thinking about how the Heck Reaction works formed the foundation for a huge swath of new reactions and continues to inspire chemists today. My own research would not be possible without the understanding that Heck gave the community,” said Watson, whose research is funded by a prestigious National Science Foundation Early Career Award, which she received in 2012. It includes an outreach component highlighting Heck’s work, which is aimed at getting high school students excited about science.

“He did all this just by 'always looking for new chemistry' and 'trying to make life simpler,'” Watson said of Heck. “He certainly accomplished these goals, redefining organic synthesis and impacting our everyday lives with his discoveries.”

Douglass Taber, professor emeritus of chemistry and biochemistry, described the impact of Heck’s work. “Before Heck, all carbon-carbon bond formation required an equal amount of metal. Dick was the first to form carbon-carbon bonds using only a small amount of the expensive metal,” he said. “This was the beginning of organometallic catalysis, now the basis of everything from pharmaceutical synthesis to polymer production.”

Taber also remembers Dr. Heck’s passion for horticulture. “When I first visited his home, in January, he disappeared into his heated greenhouse and came back with a perfectly ripe cherry tomato for me to eat.”

Don Watson, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, called Prof. Heck “an amazing and inspirational scientist and the most gentle and humble of human beings.”

He said, “Prof. Heck was a true giant in the field of synthetic chemistry and was enormously ahead of his time. His work changed how chemists think and what we are able to do. The direct and indirect impacts of his work touch on our lives, not just as chemists but as everyday citizens, in ways that most cannot imagine. The reaction that bears his name, and related reactions, have impacted a vast range of advances important to modern society — from things as mundane as sunscreens, and as advanced as modern electronics and medicines that cure human disease.

“Heck’s work has also inspired generations of scientists,” continued Watson, who received the NSF Early Career Award last year to support research on new chemical reactions, a foundation laid by Heck. “Although I was only able to meet Prof. Heck once, his impact on my own career and research has been enormous. Much of my own group’s research has been directly inspired by the reactions that Heck developed. At a personal level, I am greatly saddened by Prof. Heck's passing and will always be indebted to his pioneering advances.”

The Heck Reaction

While at UD, Dr. Heck discovered the “Heck Reaction,” which uses the metal palladium as a catalyst to get carbon atoms to connect up — a difficult feat in nature.

The discovery has enabled the production of new classes of pharmaceuticals for treating cancer to HIV, asthma, migraine headaches, stomach ailments and other maladies. The work revolutionized DNA sequencing, making possible the coupling of organic dyes to the DNA bases, which was essential for the Human Genome Project. Dr. Heck's achievements reverberate throughout our lives every day, in products ranging from sunscreens to super-thin computer monitors.

Dr. Heck’s contributions were recognized through a number of prestigious awards. In 2004, UD's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry established the Heck Lectureship, an annual award given in recognition of significant achievement in the field of organometallic chemistry.

In 2005, he was awarded the Wallace H. Carothers Award, bestowed by the Delaware section of the American Chemical Society for creative applications of chemistry that have had substantial commercial impact. In 2006, he received the Herbert C. Brown Award for Creative Research in Synthetic Methods from the American Chemical Society.

Dr. Heck last visited the UD campus in May 2011, attending a symposium in his honor on May 26, which was declared Richard Heck Day on campus. At Commencement on May 28, he received an honorary degree from the University.

Earlier this year, a display honoring Dr. Heck was unveiled in the lobby of Brown Laboratory, home of the University's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Also featured in the display is the late UD alumnus Daniel Nathans, who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1978.

Born in Springfield, Mass., on Aug. 15, 1931, Dr. Heck completed his bachelor of science degree in 1952 and his doctorate in 1954 at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA).

After a 14-year career with Hercules Chemical Company in Wilmington, Delaware, Dr. Heck joined the University of Delaware faculty in 1971. He retired in 1989.