DEOS hits one billion

Delaware's real-time environmental monitoring system makes billionth observation

1:08 p.m., Nov. 9, 2015--Meteorological and atmospheric conditions are constantly fluctuating and are important to monitor in real-time. State agencies, the emergency management community, private companies and farmers all depend on environmental monitoring data on a day-to-day basis to make critical decisions.

The Delaware Environmental Observing System (DEOS), “a real-time environmental data service provider for the state of Delaware and surrounding region,” recently reached its one billionth environmental data measurement. DEOS celebrated 10 years as Delaware’s real-time environmental data source in February 2014.

Campus Stories

From graduates, faculty

Doctoral hooding

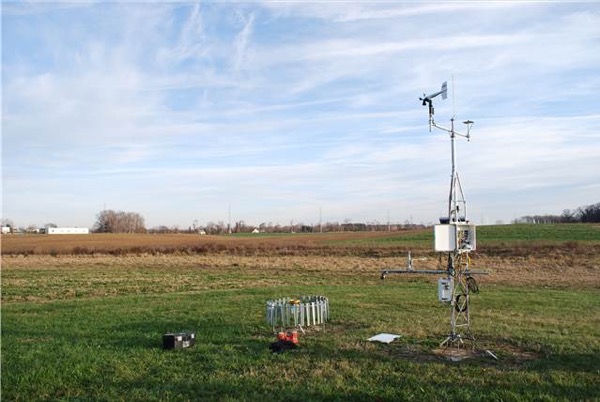

DEOS has a state-wide network of environmental monitoring stations that transmit many different kinds of data to a central repository housed on the University of Delaware’s Newark campus.

Air temperature, rainfall, snowfall, water quality, barometric pressure, relative humidity, wind speed and more are recorded in real-time. These numbers can be used in a variety of ways for forecast model initialization, crop water allocation and detailed regional maps showing current atmospheric conditions. This data is freely available through the DEOS website.

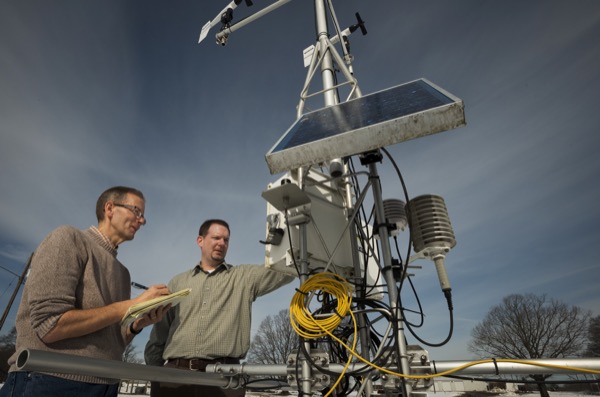

“The number ‘one billion’ doesn’t define DEOS, but the information and data provided over 11 years does,” said Kevin Brinson, director of DEOS and assistant state climatologist for Delaware. “This number symbolizes the growth [of DEOS], and the longevity of the system and is a great milestone for us.”

With measurements that refresh every five minutes, DEOS is a valuable resource to the regional community as well as various weather agencies. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) uses DEOS data to initialize forecast models and the local National Weather Service Forecast Office in Mount Holly, New Jersey, uses the data to issue weather advisories. NOAA also uses DEOS data to validate their forecasts.

Similarly, agencies like the Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT) rely on DEOS’s snowfall measurements to determine when or which major roadways need to be plowed. This real-time data is then archived for assessment so that researchers can identify weather trends and construct data sets, which include climate information such as daily and monthly average temperature and precipitation.

While comparable monitoring systems exist at other academic institutions, such as the New Jersey Weather and Climate Network based at Rutgers University and the North Carolina ECONet based at North Carolina State University, DEOS is made unique by the online environmental monitoring applications in which its data is used.

Major applications include the Delaware Coastal Flood Monitoring System, the Water Quality Portal and the Delaware Irrigation Management System.

Brinson also sees potential for DEOS as a useful tool for students, particularly those in UD’s new meteorology and climatology major, which is housed in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment’s (CEOE) Department of Geography.

“DEOS provides a wealth of data that can be used in meteorology and climatology courses,” Brinson added, to help students create and interpret weather forecasts and develop a better understanding of how the atmosphere behaves.

The system’s automated weather stations have more than just statewide implications, however; a weather station has recently been affixed to a floating Greenland glacier to aid in UD oceanographer Andreas Muenchow’s research on glacial melt distribution.

Researchers captured the first-ever measurements of the ocean conditions underneath the glacier with the weather station developed by DEOS.

Article by Cody Harrington

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson