Illuminating the dark

Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight editor advocates for investigative journalism

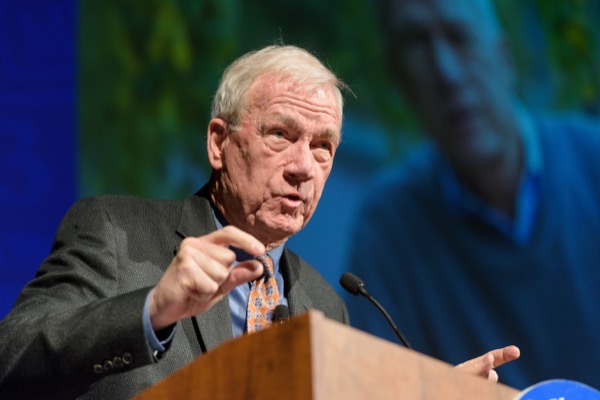

4:36 p.m., March 23, 2016--When the movie Spotlight hit theatres last fall, University of Delaware English professor Ben Yagoda invited Walter Robinson — the real-life editor who led the team of investigative journalists portrayed in the film — to speak on campus during spring semester.

Robinson accepted, “but I wondered if anyone would remember the film by March,” he said.

People Stories

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

As it happened, he had no reason to worry. Spotlight went on to win Academy Awards for best picture and best original screenplay, and a nearly full house turned out at UD’s Mitchell Hall on Tuesday evening, March 22, to hear Robinson talk and to ask him questions.

He told the audience of students, faculty and community members about how the film came to be, the painstaking work the screenwriter and director put into making its details as authentic as possible for a Hollywood movie, his own career spanning more than 40 years in newsrooms and — most of all — his continued passion for investigative journalism.

“Good reporting is often the only light that illuminates life’s darkest corners,” he said, adding that even in the current environment of “precipitously” declining revenue and readership for traditional newspapers, good journalism plays a critical role in a democratic society. “There are still great opportunities to do stories that really matter.”

The reporting project that was dramatized in the film is an example of that, Robinson said. A five-month investigation by the designated Spotlight Team of investigative journalists at the Boston Globe exposed a pattern of sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests in the Boston area and a decades-long cover-up of those crimes by church and civil authorities. The work sparked similar investigations and disclosures across the country and around the world and won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

Robinson told his audience that the filmmakers did a kind of investigation of their own into the Spotlight Team’s work, recording in-depth interviews and researching the same documents that the journalists had uncovered.

Although the resulting movie was a dramatization, not a documentary, he said, it was highly realistic in its portrayal of the reporting process.

“This film is amazingly true to what happened,” he said, even while the process of compressing five months of work into a two-hour movie necessarily eliminated much of the day-to-day routine and often tedious work of the investigation.

“Real investigative reporting is almost never exciting,” Robinson said. “The work you do to get the story is never as interesting as the story itself.”

Journalists generally like the film because of its authentic details about the characters and atmosphere of a newsroom, he said, including the “clueless reporters stumbling around in the dark” trying to decide what story to pursue and how to work it. He urged students in the audience to continue considering careers in journalism, especially with a focus on investigative reporting.

Robinson called the Internet “a double-edged sword” that has caused many of the economic woes facing traditional newspapers but also offers journalists the means to gather investigative information and uncover stories much more quickly, accurately and efficiently than ever before. Using the Internet as a tool, in combination with doing face-to-face interviews, will enable reporters to continue to pursue investigative work, he said.

“The best stories do not come to you,” he told aspiring journalists in the audience. “You have to go to them.”

Classroom visit with journalism students

Earlier in the day, Robinson met for a question-and-answer session with students in the History of American Journalism class taught by Mark Bowden, instructor in English and Distinguished Writer in Residence at UD.

“Walter Robinson has been a reporter at the Boston Globe for much longer than you’ve been alive,” Bowden told the class, which has been studying the history of investigative journalism. The Spotlight story “is very much in that tradition,” he said.

Robinson answered students’ questions about the film and the reporting project itself. He told them that newspapers remain important to society and democracy but acknowledged that the past decade has been difficult. Reporting staffs have shrunk significantly, and many editors are less willing to devote resources to in-depth, or even what used to be considered basic, news coverage.

But, he said, during a recent seven-year stint of teaching investigative reporting at Northeastern University, his students produced 26 front-page stories for the Globe. Their enthusiasm and success show that investigative reporting can still be done in spite of the current climate in which newspapers are losing readers and advertisers to online outlets, he said.

“Somebody — maybe somebody in this room — is going to figure out how to monetize good journalism again,” he told the students.

Article by Ann Manser

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson and Evan Krape