fMRI now on duty

Center for Biomedical and Brain Imaging offers researchers state-of-art facility

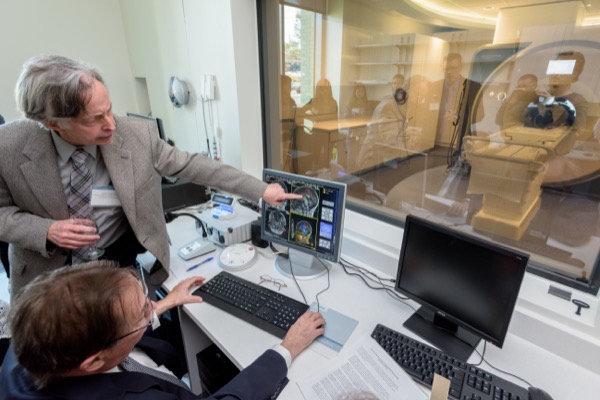

4:08 p.m., April 19, 2016--Research capacity at the University of Delaware took another long stride forward Friday with the opening of the Center for Biomedical and Brain Imaging, the second major facility added in as many months.

The new center, near the corner of Academy Street and East Delaware Avenue, holds a 3-Tesla magnet, nearly 14 tons in weight – a cutting-edge instrument that offers high-resolution images and the ability to do complex examination of brains, bones, and other biosystems and brings powerful new possibilities to UD's investigators.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

The strong magnetic field made possible by the new super-conducting magnet combines with other features to enable the stability, pure signal, and consistent results needed for useful neuroimaging.

"It's absolutely the best tool for doing this type of science," said Kenneth Norman, a Princeton University professor who delivered a keynote address on his pioneering fMRI research before the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

"This is an incredibly exciting day for research at the University of Delaware," said Charles Riordan, deputy provost for research and scholarship. "This is a core facility – of value to every one of the seven colleges at this campus."

It was just a month ago that researchers cut the ribbon on the new University of Delaware Nanofabrication Facility. The UDNF, housed about a block away in the Harker Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Laboratory, is a nanoscale workshop that allows for the most intricate of maneuvers.

CBBI's powerful new magnet – the Siemens Magnetom Prisma – offers the latest in imaging technology and is especially exciting to those studying the brain because it provides images of real-time function, showing researchers exactly where neurons are most active at any given time.

"I'm very interested in understanding how reward interacts with attention and how it changes what we pay attention to," said Leeland Rogers of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, a graduate student in the Perception and Learning Lab of Timothy Vickery, assistant professor of psychological brain sciences. Vickery, a cognitive neuroscientist, has traveled routinely to College Park, Maryland, to use the fMRI at the University of Maryland in his research.

"It has been an incredible experience already working with Tim," Rogers said. "We're all kind of learning it together. There's a big sense of community."

No exposure to radiation or shots or other chemicals is necessary in fMRI. It is non-invasive, accomplished by the powerful magnetic field that interacts with radio waves and allows researchers to see the changes in neural activity as a person views images or performs tasks.

The instrument measures blood flow, which is correlated with neural activity. More oxygen is needed in areas where neural activity is high – and blood with higher oxygen levels has different magnetic properties than blood with lower oxygen levels.

That doesn't mean a researcher can read your mind once you slide into the machine's bore, almost two feet in diameter, where the magnetic resonance imaging is done. But that might not be too far off, given a sketch of recent research described by Princeton's Norman, who was part of the pioneering team that developed an fMRI data analysis method called "multivariate pattern analysis" or MVPA.

"It's basically mind-reading based on fMRI data," said Norman, professor of psychology at Princeton's Neuroscience Institute. "We take brain scans and guess what you're thinking."

Specifically, his lab studies learning and memory by looking for patterns in brain activity that are related to specific thoughts and memories.

The fMRI provides enormous quantities of data, but using that data in valuable ways requires more than observation. Higher neural activity does not mean anything unless the reason for increased activity is understood. If the study goes from a blank screen to a face, for example, and higher neural activity is noted, it might mean only that the brain was interested in seeing something other than a blank screen. But seeing a difference in activity between images of a boot and a face or a scene and an object can provide meaningful information about how the brain processes specific information.

The MVPA method uses pattern classification algorithms to deduce what a person was viewing when the data were collected – a shoe or a bottle, for example. The overall accuracy of these computer analyses – matching pixel to pixel – has reached about 96 percent, Norman said.

Norman also is exploring competing memories and how memory is retrieved or inhibited – work that could one day help clinicians treat such conditions as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The capacity offered in CBBI goes well beyond brain science.

Dawn Elliott, professor and chair of biomedical engineering, said she is "thrilled" to have MRI capacity for her lab's ongoing study of intervertebral disc function and degeneration. Much of her study involves human spine segments and also goat spines, whose disc size and properties are similar to humans. In the goats she is gathering preclinical data that measures how well a potential treatment is working over time. If the treatment is successful, these data would be used as part of approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The new center is designed to accommodate animals, and Elliott said it will offer much more statistical power for longitudinal studies.

Christopher Modlesky, associate professor of kinesiology and applied physiology in the College of Health Sciences, will continue his studies of the musculoskeletal system in children with cerebral palsy and other conditions.

"This has a lot of advantages," Modlesky said. "It is more powerful, delivers higher quality images and now we can combine musculoskeletal and brain imaging work."

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, the ceremonial scissors went to Robert Simons, professor and chair of UD's Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences.

"Bob Simons was the driving force – a bulldog – and he continues to be a bulldog for creation of this center," said his colleague, James Hoffman, professor, interim director of CBBI and director of the cognitive psychology graduate program at UD. "I'm pretty sure without Bob Simons, this building wouldn't be here."

Several new faculty and fMRI experts have been drawn to the University by the new magnet.

Already on site is CBBI Manager John Christopher, who brings years of technical expertise to UD from the University of Virginia and said that for cancer research "there isn't anything better" than this fMRI instrument.

The new director of CBBI, Keith Schneider of York University in Toronto, Ontario, will start in August. He was on hand for the opening-day ceremony.

"The people here have done everything right," Schneider said. "They made all the right decisions. With a brand new scanner and an administration that is really supportive – that will help people do research. I'm anticipating heavy use."

Financial support for CBBI was provided by the University, the Unidel Foundation, the College of Arts and Sciences, the College of Health Sciences, and the College of Engineering.

When additional funding is available, the University hopes to add a 9-Tesla magnet to a dedicated space on CBBI's second floor and other capacities – ultrasound and micro-CT, for example – to the adjacent multimodal suite, making many other kinds of imaging studies possible.

Article by Beth Miller

Video by Robert DiIorio

Photos by Evan Krape