'Clouds and Zombies'

Study reveals best ways to use analogies in marketing

11:33 a.m., April 18, 2016--They watched, waiting for the instant the test subject smiled. University of Delaware marketing professor Michal Herzenstein and her research assistant knew what a smile meant. It was the “aha!” moment. It meant the subject “got it.” The subject, one of hundreds in a study, understood an analogy presented to advertise a new product and therefore, knew what the product did.

The study found that when it comes to really new products, ones unlike anything already in the market, the way marketers develop analogies matters. Herzenstein and a colleague from Vanderbilt University published their findings in the Journal of Consumer Psychology. Now available online, it will be printed in the coming months.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Really new products are novel items. Think, for example, of the iPad’s introduction. Consumers are unfamiliar with really new products because they defy categorization. Before the iPad, a tablet was made of paper.

Meanwhile, many companies rely on novel items as a vehicle for growth. Advertisers must find a way to adequately describe the product and convince potential customers it is worth buying.

One of the best ways to introduce really new products is through analogies, said Herzenstein, an associate professor in UD’s Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics. Herzenstein and her team sought to pinpoint the mix of elements that make an analogy convincing.

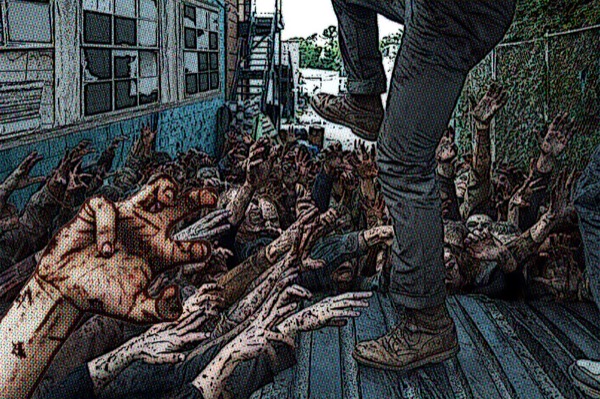

The study’s title “Of Clouds and Zombies: How and When Analogical Learning Improves Evaluations of Really New Products” might seem like a nod to the popular show The Walking Dead, a newer take on a the vintage pop culture conceit of a the undead taking over the world.

But, it is actually a reference to a particularly effective campaign run by the software company SunGard.

SunGard found customers did not understand its cloud computing services and decided to compare the company’s offerings to surviving a zombie apocalypse.

In both instances, it said, the attackers are “after your brain” and the only way to successfully survive is preparation. The analogy used “distant domains,” points of reference that are very dissimilar.

Herzenstein wanted to know why this distant analogy worked and if a closer analogy might have been more effective.

“We asked how much information do you need to give about the analogy so that consumers will have a positive evaluation of the product?” Herzenstein said.

To test, researchers developed ads for really new items. Each item had two ads – one that described it using a close analogy and another using a distant analogy.

One item marketed was Coravin, a contraption that allows the user to pour a glass of wine from a bottle without pulling the cork.

The close analogy ad began, “The Coravin wine access system is like having your own wine bar! It allows you to sample a variety of wines while preserving the remaining wine in the bottle.”

The distant analogy referenced the streaming music service Spotify. It read, “The Coravin wine access system is like having Spotify for your wine cellar! It allows you to sample a variety of wines while preserving the remaining wine in the bottle.”

Both ads contained additional information that told consumers, “you can expand your palate by comparing and contrasting tastes across multiple bottles in an evening, comparing vintages and varietals and get more creative with your food and wine pairings.”

Test subjects were each presented with just one ad and asked for their reaction. Their responses showed neither type of analogy is superior to the other. Superiority depends on the amount of information revealed in the ad.

Consumers like to figure out analogies for themselves; when the analogy is close, consumers don’t need a great deal of additional information. For test subjects who read the first Coravin ad, the extra details about expanding their palates was detrimental.

“When we give too much information, consumers are like, ‘We get it. Stop bugging us!” she said. “We rob them of the positive feeling they get from understanding it themselves.”

Meanwhile, those who read the second Coravin ad found the palate details beneficial. As Herzeinstein’s research noted, when an analogy is distant, too little information leaves consumers confused and annoyed. Marketers need to give a lot of information to help consumers understand the analogy, she said.

Finding the right balance in marketing really new products can be tricky, as can surviving a zombie apocalypse.

Article by Andrea Boyle Tippett

Illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase