Redefining customer service

In Gore Lecture, marketing expert discusses science behind satisfying customers

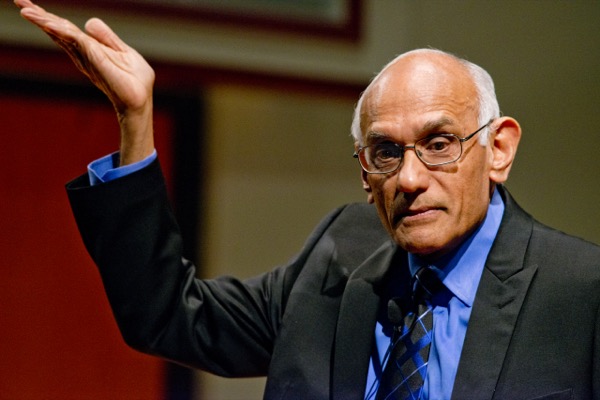

9:51 a.m., May 1, 2015--Marketing expert A. Parasuraman saw an example of his customer service research in action when he visited a hotel and was given something unexpected: a pillow menu.

“My initial reaction upon seeing this was, ‘Wow, this is great. I’ve never seen anything like this before,’” said Parasuraman of the menu, which offered nine types of pillows from which to choose.

People Stories

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

He explained that the menu improved his perception of the hotel, and his expectations as a customer rose.

“But as I started experiencing the basic service of the hotel, almost everything that should not go wrong in a hotel did go wrong,” Parasuraman said.

As the hotel committed many “fatal errors,” like the front desk failing to make promised wake-up calls, Parasuraman said he was even more disappointed than he would normally have been. This, he explained, was because the luxurious pillow menu had raised his expectations, making his eventual disappointment even greater.

Parasuraman explored this and other customer service paradoxes during his lecture last week as part of the University of Delaware’s W.L. Gore Lecture Series in Management Science. The W. McLamore Chair in marketing at the University of Miami’s School of Business Administration explained how his research quantifies customers’ day-to-day service experiences.

Parasuraman has found disappointed customers come from “a disconnect between what customers believe excellent quality service should be, and what they actually think they are getting,” as demonstrated by the pillow menu example.

He explained that, despite consistent advances in technology, service quality has not drastically improved.

“Why hasn’t anything changed?” Parasuraman asked.

His research has found that the answer might be that fundamental service problems arise from four organizational deficiencies, or “gaps,” within companies.

These gaps include the “internal communication gap” that arises when companies fail to communicate to customers what they can and will deliver.

“A lot of times there is a disconnect, for example, between the advertisements that the company puts out and promises to customers, and what the customers actually experience,” Parasuraman said. “We are all victims of that.”

Parasuraman calls this gap a result of a serious communication failure between marketing departments and operations departments, “between the so-called ‘promisers’ of the service and the providers of the service.”

The pillow menu is an example of another gap known as the “market information gap,” or when companies fail to understand what customer expectations really are.

“How many of us as customers of hotel services have the expectation of being offered nine different pillows?” Parasuraman asked. “I would say zero.”

He explained that companies waste a significant amount of money and resources on ideas like this one.

“But was my quality of service perception higher?” he asked. “I would argue that because of the pillow menu, my quality of service perception was lower.”

“Not only are those resources going to be wasted, they are going to unnecessarily increase the customer’s expectations as well,” Parasuraman continued. “I sometimes refer to this gap as a ‘double-whammy gap,’ because it channels resources in the wrong direction and at the same time it also aggravates customers.”

Examples like this, which negatively impact both customer service quality and productivity, make it easy to see how Parasuraman’s research connects the two fields.

“The internal organizational gaps that relate to service quality also adversely affect service productivity,” Parasuraman explained.

Measuring these gaps, he said, “offers a way of thinking about quality of service systematically and also starting to think about how we can approve quality of service.”

But companies, the marketing professor noted, must “start internally, not doing customer research or customer surveys, but to take a close look at what’s happening within the company and try to close those gaps.”

In addition to his gap-based SERVQUAL research, Parasuraman has also worked to measure a number of important and seemingly intangible factors in the realm of customer services.

This includes the “zone of tolerance,” a range of service quality which customers will accept from companies.

“Most customers are actually quite reasonable,” Parasuraman said. “Even though ideally they would like a certain level of service, they do cut companies a certain amount of slack.”

“As long as the service delivered by a company is within the zone of tolerance, customers will be satisfied, if it’s below the zone of tolerance they’ll be upset and if it’s above the zone of tolerance they might be delighted,” he continued.

Another important measure developed by Parasuraman’s team is the Technology Readiness Index (TRI), which measures “people’s propensity to embrace and use technologies for accomplishing goals in home life and at work.”

The TRI is important in determining whether a company should utilize high-tech or what Parasuraman calls “high-touch” services, which emphasize human connection and interaction.

About the Gore Lecture

The W.L. Gore Lecture Series in Management Science, presented by UD’s Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics, is sponsored by an endowment from the Gore family.

This lecture series features experts in the application of probability, statistics and experimental design to decision-making, including applications in academia, business, government, engineering and medicine.

The series recognizes the key role that the fields of probability, statistics, and experimental design have played in the success of W.L. Gore & Associates Inc.

Article by Sunny Rosen

Photos by Lane McLaughlin