Photograph restoration

Art conservation graduate students restore charred family photos after deadly fire

6:03 p.m., Jan. 14, 2015--It’s the kind of painstaking work more often done for pharaohs, kings, Rembrandts and du Ponts.

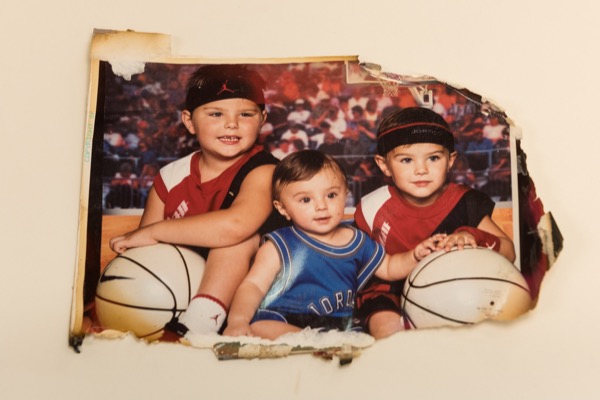

But now, a team of first-year Winterthur/University of Delaware art conservation graduate students is working fervently on behalf of a family in rural Ohio that lost four members -- including three young brothers -- in an early-morning fire the day after Christmas.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Under the guidance of Debra Hess Norris, Unidel Henry Francis du Pont Chair in Fine Arts and chair of UD’s Department of Art Conservation with expertise in photograph conservation, the team is examining, evaluating, and gently restoring 300 charred, water-damaged photographs rescued by someone at the fire scene.

The photos came to the University through Michael Emmons, who is in the University’s doctoral program in preservation studies and was a close friend of the boys’ father during high school.

Emmons asked for Norris’ advice on addressing the damage and she offered to have her students evaluate and work on the photos during their first-year photograph conservation block, which was to start Jan. 5, just 10 days after the fire.

The photos were delivered to Winterthur, where Norris’ class is held, and work started immediately.

The goal is to clean, flatten and stabilize the photographs, which include school portraits, Polaroids, photobooth prints and snapshots, some 8x10s, many in color, some black-and-white. That process will prevent further deterioration, but some items will still carry scars so the conservators will prepare the images for scanning, housing each conserved photograph in polyester sleeves with acid-free paper containing zeolites to further absorb smoke odor. Some images will be digitized and the damaged areas cropped, but the primary focus is on the preservation of the originals.

“It has been powerful,” said Leah Bright, a native of Fairbanks, Alaska, who is majoring in object conservation. “It is so personal and emotional for the family, and our priority is to help them.”

The effort -- hundreds of hours so far -- has been a balm for the surviving Harris family.

“We’re pretty blown away by the fact that somebody wants to take interest and care about this tiny little family,” said Ricky Harris, who lost his three sons -- Kenyon, 14, Broderick, 11, and Braylon, 9 -- and his mother, Terry Harris, 60, in the blaze. “You tell them that me and my family, my whole family -- we love them all. There’s no words to say how appreciative we are.”

The fire and its aftermath

Emmons was in Ohio during the holidays when the fire occurred. He had planned to visit his father on his way home to Delaware, he said, but went instead to offer support to his devastated friend.

The three Harris brothers, who lived just two doors from their grandmother, had gone to spend the night at her home so she wouldn’t be alone on Christmas night. The fire broke out shortly after 4 a.m. on Dec. 26 and swept quickly through the small ranch house on rural Inskeep Road near Washington Court House, Ohio.

“We ran down there,” Ricky Harris said, “and it was like a bad dream. You just keep thinking, surely your kids aren’t in this house, your mom is not in this house. I talked to the sheriff and I just kept waiting for them to tell me they already left in an ambulance.”

Only his mother’s dog escaped, Harris said. Almost everything else was reduced to ash.

Emmons arrived the day after the fire and went to Harris’ house, looking for him. When he didn’t find him at the house, he checked the garage. But when he opened the garage door, he was immediately hit with the smell of smoke and was startled to see photographs spread all over the floor.

Someone had grabbed them from the scene, dripping wet from the work of the fire hoses, and spread them out on the garage floor to dry.

“That was pretty much all you could see -- they were wall to wall,” he said.

As he considered how to help his friend, Emmons focused on those photos. He remembered how important photographs had been to him the year before, when his brother died. He scanned all the photos he could get his hands on.

“For me, it was part of the healing process,” he said.

He sent an email to Norris, asking if she had any advice on whom to consult, and she called him back within an hour, he said. Soon the boxes were packed and shipped to Winterthur, where Norris’ three-week block class would start work on Jan. 5.

Conserving the photos

Though many of the 10 fellows in Norris’ program had little or no previous experience in photograph conservation, all were accomplished emerging conservation professionals with demonstrated skills and knowledge and a commitment to the preservation of cultural heritage.

Selection to the three-year graduate program is limited and very competitive. The Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) is one of only four graduate-level programs in the nation, and Norris’ skills and experience in photograph conservation -- from daguerreotypes to digital prints -- are internationally known.

Disaster response has been one focus of her work, which has made her a sought-after consultant in many areas of the world. She leaves next week for Beirut.

“Her passion is so contagious,” Bright said. “We’re all thinking, do we want to be photograph conservators now? You can’t help but feel really strongly about preservation in a project like this.”

The work this month, with its tragic background, unfolded in unexpected ways. It was not on the syllabus, of course, but it offered many learning opportunities as well as a means to help a family in a time of crisis.

There was no time to waste.

“In the event of a disaster, you want to respond quickly,” Norris said. “Soot can become embedded if you wait too long.”

Students expected to open the boxes and start to sort through the photos to determine the best approach, said Samantha Owens, who has a degree in art history from Emory University.

But when the boxes were opened, the acrid smell of smoke filled the room and had to be addressed.

“We had to brush off soot, using a soft brush so we did no damage, and get the loose particles off,” Owens said.

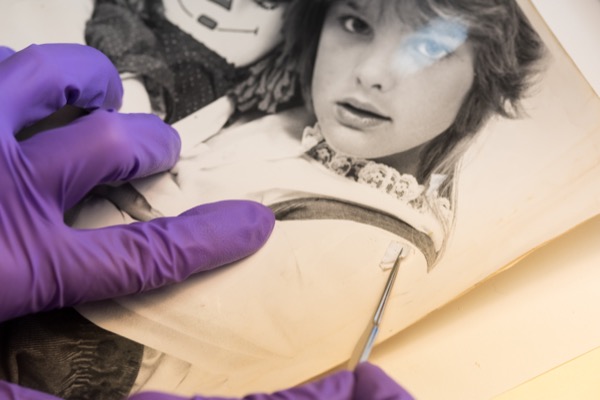

Students use ultra-soft hake brushes for such work, often studying the surface of the photograph with a stereomicroscope first to see more precisely which areas are blistered or damaged.

“Using the microscope you can see where areas have melted, where it is bubbly or blistering, where some of the paper has shrunk, resulting in ridges of plastic,” said Madeline Corona, who has degrees in chemistry and history from Trinity University. “It’s amazing that so many have survived.”

The fiery smell also was addressed with the use of zeolites from volcanic rock. Zeolites are minerals that sometimes called “nature’s deodorizer” because they attract gases and liquids that cause odors. They also help to remove moisture.

Many photos arrived sealed together and had to be carefully detached, where that was possible. At times, the gelatinous binder on the photo paper merged completely with that of an adjoining photo or protective sleeve.

The photos presented a cross-section of the history of photography, too, with some from the 1960’s, ’70’s and ’80’s. Some had different coatings and dyes on paper and resin-coated paper supports.

“Each photograph varies,” Norris said, “deteriorated in different ways, dependent on their location in the fire or prior natural degradation.”

Part of the work was to remove stains or dyes that had marred the surface. Cosmetic sponges and small erasers were among the tools used. Ethanol, water, and even saliva were used on small cotton swabs to clean parts of photos, depending on what was needed. Ethanol does not swell the gelatin as much as water. The enzymes in saliva break down proteins and can aid in the removal of foreign material, Owens said.

Small tests were done before any particular method was applied to be sure no damage would be done.

After cleaning and stabilization, the photos must be flattened. Many had curled or warped where water had hit them in the aftermath of the fire. They would be gently humidified, covered with a polyester web, placed between blotters, and allowed to dry slowly.

As students worked, they recorded their findings and methods, creating a wiki that they will post online to provide guidance for anyone anywhere who might be faced with a similar challenge.

Ethical considerations were discussed at every step, approaching the objects with the utmost respect, Norris said.

“We considered taking off the badly damaged edges, thinking the family might have trouble looking at them,” said Gerrit Albertson, who has a degree in art history from Vassar. “But we were not comfortable being that intrusive.”

Instead, they decided to prepare the photographs for scanning where damaged areas could be cropped, in case the family wished to have unmarred copies.

“In some ways, it is frustrating,” he said. “You want to get rid of every blemish. That’s not always possible.”

Power of art conservation

The work illustrates the power of conservation efforts at every level of society and worldwide.

“These are personal treasures, not just things on a pedestal in a museum,” said Alexa Beller, a native of Illinois studying paintings conservation.

And though the pain of this unspeakable loss is fresh and wrenching, “there will come a time when they will want to view these photos,” said Ibrahim Abdel Fattah, an object conservator from the Grand Egyptian Museum who has been documenting the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun and is studying photograph conservation as a guest participant in the course.

The young conservators are helping to make that possible.

“There are generations in these photos,” said Josh Summer, a South Carolina native with a background in photography and a focus on paintings conservation. “It’s a record of history and a record of an event and what that event means not only to the family but to everyone in the community. They may not want to look at it right now, but in the future, who knows? Our job is to make sure that can happen.”

Back in Ohio, Ricky Harris said he already has seen some of the photos posted online -- photos of his boys, his sister, other family gatherings.

“My brother-in-law and I were talking about it on the phone last night,” Harris said. “He said it felt like his chest hurt and his bones ache. Our hearts are broken. But to see those photos online and be able to scroll in and be able to see that those are our pictures -- oh. That this great big place that could be doing so many other things is doing this for us, it helps.”

Article by Beth Miller

Photos by Evan Krape

Video by Ashley Barnas