Part 5: A tale of two poles

Marine organisms illuminate the Arctic during polar night

(Editor's note: This is the latest installment in a continuing series on research being conducted by University of Delaware scientists in the Arctic and Antarctica this month. For the Jan. 12, Jan. 15, Jan. 21 and Jan. 26 postings, scroll down the page.)

10:46 a.m., Feb. 2, 2015--Studying light in the darkness may sound like a play on words but this is exactly what the University of Delaware’s Jonathan Cohen is doing in Svalbard, Norway.

The Arctic region is experiencing “polar night,” a winter phenomenon that occurs annually when the North Pole tilts away from the sun, plunging the area into near continuous darkness.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Cohen, an assistant professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment’s School of Marine Science and Policy, is studying how marine organisms — such as krill and sea jellies — perceive light, and how they use it to find food, to avoid predators and to mate.

The work involves measuring how much light is available for marine animals to see, both from the atmosphere (sunlight, moonlight, and aurora borealis) and from biologically produced light from the marine animals themselves (bioluminescence).

Cohen is conducting a study of light at different times of day; measuring the amount of light and its color, which both change considerably depending on the position of the sun, moon and auroras.

“Ultimately, we want to understand the light conditions underwater, but conventional light meters are not sensitive enough, so we measure light in air, then use mathematical models to predict the underwater light field,” explained Cohen. “From there, we ask questions about how marine organisms are using that light.”

Images taken during a recent 24-hour light measurement study revealed interesting differences in the sky throughout the day. At noon, the sky was perfectly clear, but by midnight over half the sky contained a spectacular display of bright green northern lights (auroras). At dawn the auroras had diminished some, but the moon, which was close to setting, exhibited a strong orange color.

“All of this influences the light measurements,” said Cohen, who is attempting to relate the sky conditions to the light measurements.

He also is conducting laboratory experiments on krill vision in order to determine how temperature and background light levels, which are both expected to increase with climate change, affect the krill’s ability to detect light.

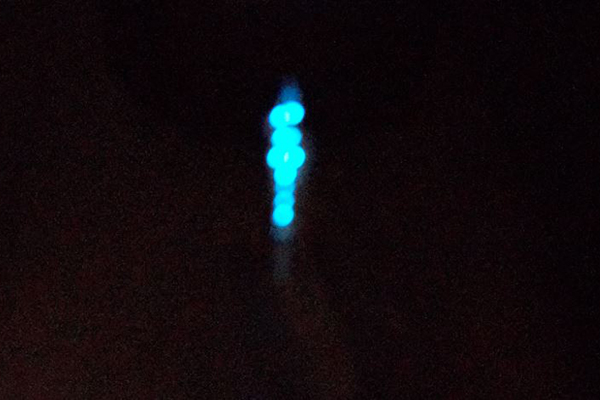

Krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans, are an important part of the Arctic food web. In the water, they glow with amazing colors as they emit bioluminescence from their ventral photophores, essentially small light bulbs on the animal’s underbelly.

Close up, the photophores resemble pinpoints of light, but from a distance the light from each photophore merges, making it difficult for predators to distinguish the animal from background light coming from the water’s surface.

“The emitted light helps the krill blend into the background light coming from the surface; this is called counter-illumination,” Cohen said.

Cohen is documenting how other tiny marine organisms, called zooplankton, illuminate the Arctic, too. Copepods, for example, release thin trails of bioluminescent light behind them as they swim, while ctenophores, jelly-like animals that resemble jellyfish, produce splotches of light visible in the glowing ocean.

Jan. 26 posting: Tracking penguins, rescuing robots

Tracking penguins and rescuing underwater robots is all in a day’s work for UD marine scientists Matthew Oliver and Megan Cimino.

Over the last few weeks, the researchers tagged Adélie penguins with satellite transmitters to help the research team understand where the penguin parents find food, primarily krill -- small shrimp-like crustaceans.

Adélies are one of three penguin species that nest along a strip of land called Biscoe Point, about 10 miles from the researcher’s home base at Palmer Station in the West Antarctic Peninsula. According to reports on the Project CONVERGE blog, Adélie penguin population numbers have declined over the last 20 years.

In a few weeks the penguin researchers will measure the weight of the chicks before they fledge, to gain a better idea of the hatchling’s probability of survival.

The UD team, which is housed in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, also collaborated with a research team specifically studying krill, using an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) called a glider to measure the water temperature near Palmer Station, as well as the amount of phytoplankton beneath the water’s surface.

Connecting the dots between the phytoplankton -- microscopic plants -- and the krill that feed on them, along with the penguin feeding habits, may help scientists start to paint a picture of what’s happening with this native Antarctic species.

The UD glider is deployed in the middle of Palmer Deep, an underwater canyon, collecting data to help researchers understand how the water column’s temperature, salinity, chlorophyll levels change over time. This will allow the scientists to see if winds, tides or internal waves can affect the stability of the water column. In comparison, gliders from collaborating institutions Rutgers and University of Alaska, Fairbanks are doing transects along and across the canyon to look at spatial variability.

The researchers unexpectedly had to rescue one of the group’s gliders after it didn’t check in for over eight hours. They suspect the glider got stuck under water in some kelp, but was able to jettison the extra weight it carries for just such emergencies in order to resurface. Once above water, the glider reported its location and Oliver was able to pull it to safety.

During the rescue, he and a colleague noticed icebergs that had drifted into the water over Palmer Deep. They quickly triangulated the iceberg’s locations and relayed the information to the pilots of the other gliders in an effort to prevent any further mishaps with the gliders still in the water.

Jan. 21 posting: At the bottom of the Arctic Ocean

UD researchers Mark Moline and Jonathan Cohen are now in the archipelago Svalbard, north of mainland Norway, studying how marine organisms cope with prolonged winter darkness. They are part of an international research team trying to understand whether marine organisms go dormant during the winter months.

The Arctic region is experiencing “polar night,” a winter phenomenon that occurs annually when the North Pole tilts away from the sun, plunging the area into near continuous darkness. Even at noon, the researchers must use flashlights to illuminate their path from the marine laboratory back to town, as the sun barely moves above the horizon.

Moline, director of the School of Marine Science and Policy (SMSP) in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment (CEOE), recently took a chilly dive in 33 degree Fahrenheit waters to better understand what happens at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. To see what he found, watch video footage of Moline’s dive.

Meanwhile Cohen, a marine scientist in the college, is investigating how marine organisms sense light and the limits of light perception in the polar night.

Coincidentally, while UD researchers are at polar opposite sides of the Earth in Antarctica and the Arctic, according to Douglas Miller, an SMSP associate professor, the CEOE study abroad group in New Zealand is positioned at almost exactly the same latitude south of the equator as Delaware is to the north.

Stay tuned for more details on what’s happening near the poles in an upcoming post.

Jan. 15 posting: Underwater robots in Antarctica

It’s been a visual smorgasbord for University of Delaware marine scientists on the way to the Antarctica. From sightings of black and white dolphins that look like pandas, known as Commerson’s dolphins, to a curious leopard seal, to an iceberg that resembled Queen Elsa’s castle in the Disney movie Frozen, the sights have been nothing short of breathtaking.

UD professor Matthew Oliver and Megan Cimino, a doctoral student in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, and collaborating researchers recently deployed underwater robots -- torpedo-shaped gliders -- over Palmer Deep to learn more about what’s going on under the water’s surface. The robots can stay in the water for weeks at a time while sending back data every few hours, such as water salinity, currents and photosynthetic activity.

Oliver and Cimino are studying the local physical processes that affect how Adélie penguins forage for food, and the data from the glider about what’s happening below the surface is an important part of the work.

“We think convergence zones are concentrating the food web (phytoplankton and krill),” Oliver said in a Project CONVERGE post. “So these gliders are going to go fly through those zones and find out if that’s true.” The effect of convergence zones is one of the team’s scientific hypotheses, and the gliders provide a way for them to test their hypotheses.

The researchers are currently stationed out of Palmer Station, Antarctica, over 7,000 miles from Delaware. The current weather in Palmer Station is surprisingly balmy at 37 degrees, compared to 30-degree temperatures reported in Newark, Delaware this morning.

To view the Palmer Station webcam or the Torgerson Island Penguin Cam, click here.

Stay tuned for details on what’s happening in the Arctic in an upcoming post.

Jan. 12 posting: Opposite ends of the world

University of Delaware marine scientists from the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment (CEOE) are on opposite ends of the world this month, studying Adélie penguins in Antarctica and sea jellies and other marine organisms in the Arctic.

CEOE scientists Matt Oliver, Megan Cimino and team are at Palmer Station on the West Antarctic Peninsula. They are investigating the local physical processes that affect how Adélie penguins forage for food, as part of Project CONVERGE, a collaborative research project between Rutgers University, UD, the Polar Oceans Research Group and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Last fall, the team reported a connection between local weather and penguin chick weights in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Researchers Mark Moline and Jonathan Cohen are headed to the archipelago Svalbard, north of mainland Norway, to study how marine organisms — such as krill and sea jellies — survive when the sunlight disappears in the Arctic. Part of an international research team, the work builds on a 2014 excursion exploring how sea life copes with continuous winter darkness.

Article by Karen B. Roberts

Photos by Geir Johnsen, NTNU/UNIS, and Jonathan Cohen, University of Delaware