Challenging our past

Book focuses on race relations between Native Americans, African Americans

3:58 p.m., Nov. 14, 2013--It’s a rosy picture, to think of Native Americans and African Americans embracing one another over the course of our country’s history.

But that rosy picture has a dark side, one tainted by tense race relations little discussed in the academic literature, pop culture and history textbooks, according to the University of Delaware’s Arica Coleman.

People Stories

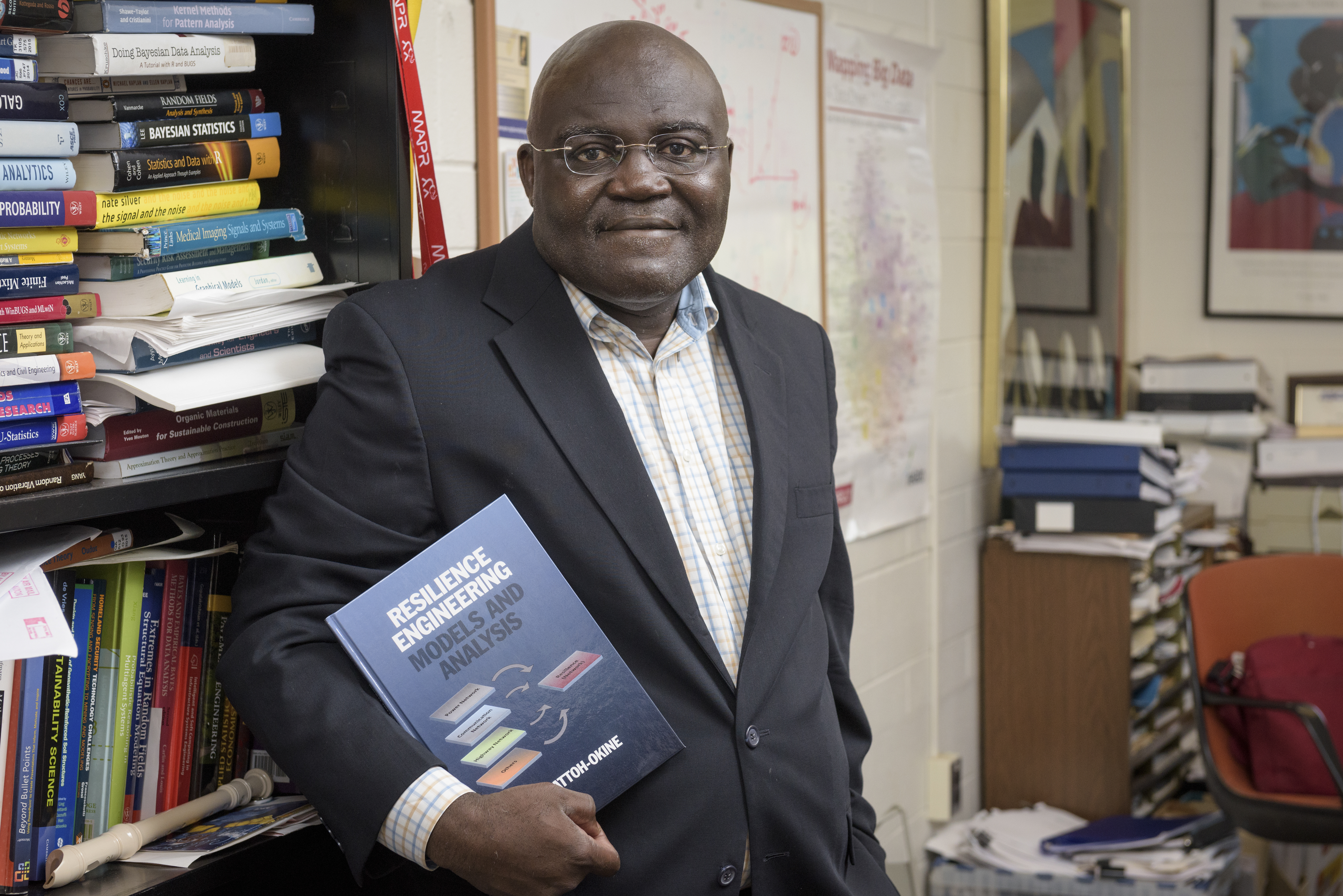

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

It’s this dark side that the assistant professor of Black American Studies explores in her recent book, That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia, published in October by Indiana University Press.

“I’m bringing to light a story that hasn’t been told before,” said Coleman, who is of both African American and Native American descent.

The story that has been told, looking primarily at only a subset of Native American tribes, has been too focused on black and white, Coleman argues, and as a result, we have missed the shades in between.

“The paradigm of the black-white binary, as far as race is concerned, is obsolete,” she said. “It’s more complicated.”

In the book, she tackles the issues that illuminate the reality that race isn’t just black and white. She takes a hard look at the state of Virginia and its history of fighting to maintain racial purity, and she looks at how race plays into the identities of Native American and African American families.

As in many black families, Coleman said that while growing up she had heard many times -- too many times -- “we got Indian in our family.” She was skeptical, but curious why her great-aunt would discuss it but her grandmother would not.

So Coleman traced her roots back to the slave trade in King George County, Va., and began to uncover a subsequent gold mine — one that shines in That the Blood Stay Pure.

Native Americans initially viewed African Americans, like whites, as intruders. But it wasn’t long before they mixed, married and started families. That is, for a while.

In 1924, Virginia passed the Racial Purity Act, in which people were categorized at birth as either “White” or “Colored.” After the Colonial period, African Americans and Native Americans has been labeled as Negro, mulatto or free colored. The Negro and mulatto labels persisted for both communities after slavery, but by the early 20th century, Native American communities insisted that they be identified as Indians.

By 1930, once-distinct Negro, Indian and mulatto labels were dropped in favor of simply White or Colored.

The land grabs began in the era of slavery, where Whites legally snatched up property owned by Native Americans, justified by the fact that they were “Colored,” no longer Indian. Whole reservations were lost.

Native Americans identified as Colored were later subjected to Jim Crow laws and other prejudices originally ascribed to African Americans.

Then there was the proliferation of the myth of the “one drop rule.”

“It’s so called because one drop of African American ‘blood’ makes you black,” said Coleman. To figure it out, all one had to do was take the comb test. If a fine-tooth comb got caught up in the hair of a Native American, there must be “Black in their blood.”

Native Americans began to deny their blackness.

Over and over again, Coleman heard of Native American families completely denying relatives over claims -- real or perceived – that they were African American. They began to send their children to special Indian schools out West, unable to send them to White schools but unwilling to send them to local Colored schools out of fear of being racially reclassified. Churches divided, separating African Americans from Indians, some of whom were related.

Coleman talked about one of the experiences she had in Virginia in 2003 that ultimately led her to write That the Blood Stay Pure.

“I talked to a woman whose Indian cousin had just a few weeks before refused to speak to her in the grocery store,” she said. “And I said, ‘What is this that would make family members deny one another?’”

One of Coleman’s informants summed it up poignantly when she stated, “We are who they are, but we are not Indians.”

Racial purity, in the context of Virginia’s racial politics, meant the absence of blackness, and it seemed more important than keeping families together, Coleman said. It pitted brother against brother, sister against sister. Tribal members of visible African ancestry and those who affiliated with or married Blacks were disavowed. The same was not true of those affiliated with Whites.

“It became more about who you were not rather than who you were,” said Coleman.

In That the Blood Stay Pure, Coleman narrates these experiences. But she also devotes a chapter to Virginia’s Nottoway Tribe, which fought against the prejudices of the time, refused to deny their African American ancestors, held on to their lands and gained federal recognition in 2010.

Coleman calls the Nottoway a “saving grace.”

“What this books does is go beyond the accepted narrative,” said Coleman. “As the saying goes, history is written by the victors. … We have to tell our stories, to push back against the accepted narrative which always seeks to invalidate those on the margins.”

Coleman has embraced her Native American heritage. She regularly participates in local powwows and has set the record straight in her own family.

“I am as comfortable at a Kwanzaa celebration as I am at a powwow,” Coleman said.

That the Blood Stay Pure has already garnered the UD professor a lot of attention. She was the subject of an article in Indian Country Today, one of the country’s leading Native American news sources. She was interviewed for a local National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate, and she is participating this month in American Indian Heritage Month at the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington as an invited speaker.

And she’s already working on her next book.

Article by Kelly April Tyrrell

Photo by Evan Krape