Building Africa

UD undergraduate visits Ghana to study nation's construction practices

2:16 p.m., May 16, 2013--Imagine looking at the same horizon for 10 years and seeing only half-constructed buildings. This is the reality for many in the West African nation of Ghana.

Why does this happen? The reason is simple. The Ghanaian public believes that cement and steel buildings connote prosperity and they hold a stigma against indigenous construction practices.

Global Stories

Fulbright awards

Peace Corps plans

However, Ghana does not have access to the resources required to make the modern materials, which requires them to import most if not all supplies and causes building costs to skyrocket.

“Their dominant building material is Portland cement, which is not readily available in Ghana. As a result, they need sites to import the raw materials to make the cement,” said David Liebers, an energy and environmental policy senior working with the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy (CEEP) who spent approximately two weeks studying the construction practices of Ghana for his dissertation.

Working in collaboration with the Millennium Cities Initiative (MCI) and a research team from Columbia University, Liebers intended to study the construction of a center for women and children just outside of Kumasi, Ghana’s second largest city, and offer suggestions.

Upon arriving, however, Liebers quickly broadened the scope of his research to include construction practices of the entire nation. Specifically, he strove to understand why so many buildings in Ghana go unfinished, and why more cost-efficient building materials remain unutilized.

“All of the wealth coming into Ghana basically comes in to the major city, Accra, where you see widespread construction. Unfortunately the wealth doesn’t spread, and an outlying area such as Kumasi remains just a large village,” said Ismat Shah, Liebers’ adviser, travel partner and UD professor of materials science and engineering and physics.

In addition to the expensive imported materials the country’s builders prefer, the lack of a reliable construction loan system forces construction to start and stop constantly. According to Shah, an average residential building could take up to a decade to complete, and many are never completed at all.

Local organizations, such as the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, have attempted to combine indigenous and modern construction styles and introduce a kiln fired red brick, made almost entirely out of local materials, to Ghana consumers.

“Resources such as clay, bamboo and timber are readily available. Although these may seem like indigenous construction practices, the cost savings could enable Ghana to build its infrastructure more quickly and efficiently,” said Liebers.

“Construction is the pulse of a country. The intensity of construction in a country reflects the boom in the economy,” remarked Shah in a report following his trip.

Liebers said he believes the UD representatives had “a pretty big impact,” adding, “All things considered, the trip was a mind-altering experience.”

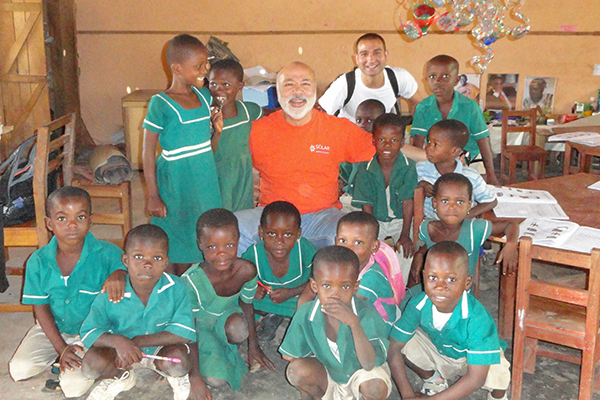

In a separate project, Liebers and Shah visited a local primary school. The teachers there told them that the children’s greatest need was toys. Since returning to the United States, Shah has raised money, which he plans to send to a colleague in Ghana to purchase and deliver toys to the children.

Article by Gregory Holt